As the steadier measures of inflation (core, median, or sticky depending on your preferences) have started to overshoot expectations slightly – the y/y measures continue to decline, but slower than expected as the m/m numbers have surprised on the high side – the markets have continued to price Fed policy becoming increasingly easier over the course of 2024 and into 2025. While Fed officials continue to push back gently on this assumption, it seems that most of the FOMC is comfortable with the idea that there will be at least some decrease in overnight rates later in the year and the only question is how much.

While inflation has not been settling gently back to target, there have developed two big holes in the narrative that the Fed was depending on. First, there is no reason to think that rent of shelter is going to cross over into deflation, either in 2024 or any time in the future. The belief that the CPI for rents would follow the high-frequency data into deflation was never well-founded, despite some fancy-looking papers that claimed you could get three pounds of fertilizer out of a one-pound bag if you just squeezed it the right way (I discussed “Disentangling Rent Index Differences: Data, Methods, and Scope”, and why it wasn’t going to tell us anything we didn’t already know, in my podcast last July entitled “Inflation Folk Remedies”), and while rents are declining they are not plunging, and home prices themselves have turned back higher and are growing faster than inflation again.

Second, core-services-ex-rents (so-called ‘supercore’) inflation needed to see wages decelerate a lot in order for that piece to get back towards target. They haven’t, and it hasn’t.

This isn’t to say that these things may not eventually happen, but so far the expectation that we would get back to target sustainably by the middle of 2024 looks quite unlikely. Why, then, are people talking about when the first eases will happen? The only way that it makes sense to do so is if the goal to get inflation back to 2% sustainably is no longer driving policy.

This has led to some observers pointing out that the Fed doesn’t actually have a 2% target any longer. In 2019, the Fed moved to Flexible Average Inflation Targeting, or FAIT. Under this rubric, the Fed doesn’t need to regard 2% (or about 2.25% on CPI) as a target that they need to hit at a moment in time but only as an average over some period of time. This obviates the need for overly-aggressive monetary policy in either direction, such as the instantaneous adjustment linked directly to the inflation-miss that is required by the Taylor Rule.

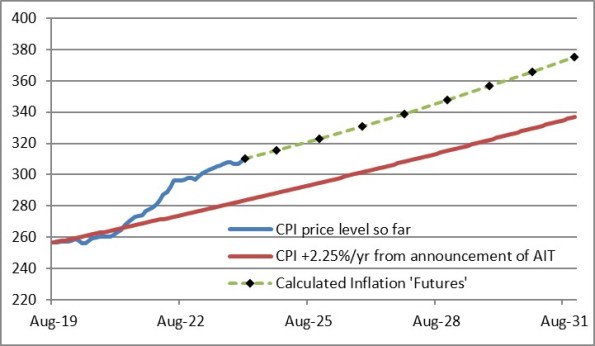

Unfortunately, under that rule the Fed has little if any chance of meeting its mandate. It would have a better chance of hitting 2% in…um…let’s say a ‘transitory’ way, as rental inflation swings lower and we pass close to the target briefly before inflation goes back up to its new equilibrium level. Back in August 2021 I noted that the Fed was already above the FAIT projected from the announcement of that policy, and in fact had used up all of the post-GFC slack. Obviously, it has gotten worse since then. Below, I update the two charts from that article. The first chart shows the CPI from August 2019, along with the average-inflation-targeting line and the forwards suggested by the CPI swap market (showing where inflation futures would be trading, if they were trading).

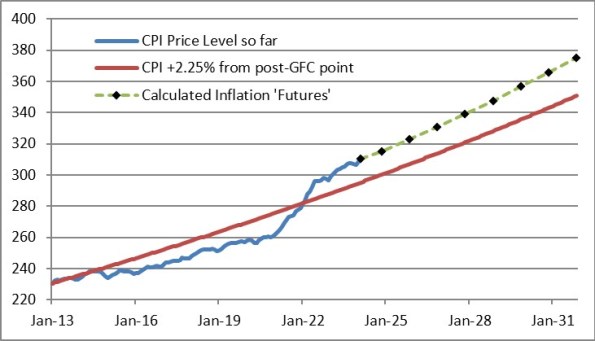

The second chart shows the CPI back to January 2013. We’ve made up all of the inflation from the post-GFC deflation scare, and then some.

Note that the inflation swap market is not indicating any expectation that prices will return back to the trendline. The market is acting as if the Fed is still operating under the old rules, where the goal was to get inflation to be stable at 2% from here, wherever “here” is. This means one of four things will have to happen, or it implies a fifth thing.

- The Fed needs to re-base its FAIT to start from the current price level. In that case, the red CPI-plus-2.25% line will shift abruptly upward but then will parallel the inflation implied by the inflation market; or

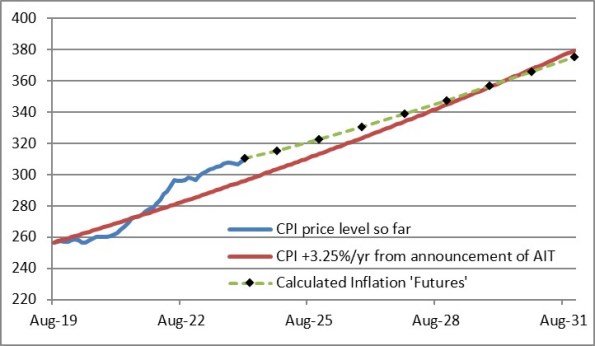

- The Fed can keep the original base, but concede that the actual target now is 3% (about 3.25% on CPI), which means that if the inflation market is right then it should be back on target by late 2029 (see chart); or

- The Fed can dedicate itself to fighting inflation for much longer, and publicly disavow the notion of reducing interest rates in the next few years. If CPI went completely flat then the Fed would be back on the line by sometime in 2028.

- The Fed can abandon FAIT, because it has become inconvenient, and validate the inflation market’s assessment that the Committee would be happy with 2% from here, not on average.

If none of these things happens, and the Fed then implies that the inflation market is going to permanently imply something different from what the Fed claims to be its modus operandi. In that case, it would be very hard to argue that the central bank had not lost credibility, wouldn’t it?