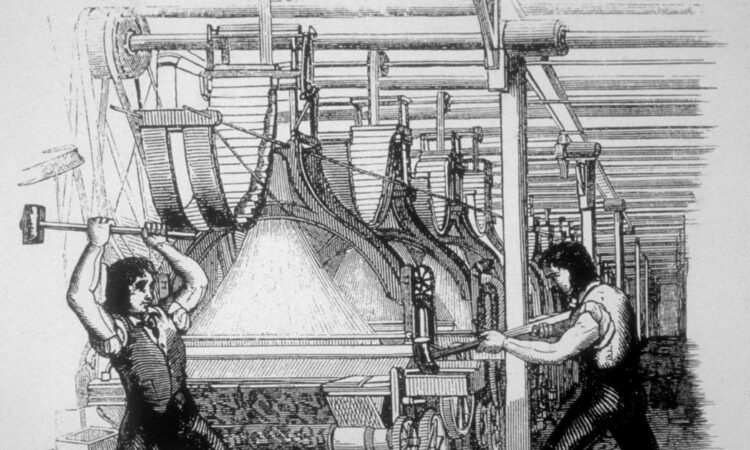

Destruction de machines par les Luddistes (le mouvement contre la mécanisation de l’industrie … [+]

Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Voltaire famously said that “common sense is not so common.” Nowhere is this adage more relevant than in the field of energy policies in the European Union. These policies are most vigorously pursued in Germany—Europe’s industrial powerhouse—since it adopted the Energiewende legislation in 2010. The regulations and mandates adopted are simultaneously hostile to fossil fuels and nuclear energy. Energiewende (German for ‘energy turnaround’) refers to the ongoing energy transition to an imagined future of low carbon, environmentally sound, reliable, and affordable energy supply.

On Friday, Pierre L. Gosselin published an article that asked in all seriousness, “The ‘greener’ Germany gets, the bloodier its economy becomes. How much can an economy bleed before it dies?” In all the economic gloom afflicting the country for the past year, there are signs that voices of reason might emerge which inject common sense to energy policy in Germany and in Europe more broadly.

Joseph C. Sternberg of the Wall Street Journal suggests that European governments might well learn the commonsense lessons of poor energy policy and the economic misery that inevitably ensues before their counterpart in the U.S.: “You know you’ve stumbled through the looking glass when European politicians start sounding saner on climate policy than the Americans do. Well here we are, Alice: Europeans are admitting the folly of net zero quicker than their American peers.”

The Anatomy Of Deindustrialization

Germany’s industrial production peaked in November of 2017, and by the end of last year had fallen to a level last seen in 2006 outside of the global financial recession and Covid-19 years. Its industrial sector contracted by almost 14% in the 6 years ending December 2023. It is no surprise that a spurt of headlines greeted news of Germany’s experience of official recession last year:

The Economist (August 2023): “Is Germany once again the sick man of Europe?”

Forbes (October 2023): “Germany Is The ‘Sick Man of Europe’: What It Spells For The Euro”

Bloomberg (January 2024): “Germany was literally a sick man last year”

German Industrial Production Excluding Construction

Mish Talk

Since the beginning of last year, the German economy contracted for five consecutive quarters on an annualized basis. Germany’s energy policies have made fuel and power prices among the world’s highest. Germany’s Federal Statistics Office reported in November that the number of year-on-year insolvency applications continued to rise by double digits since June; the number of bankruptcies rose by more than a third since August.

Energy-intensive trade-oriented industries, involving small and medium-sized firms as well as behemoths like BASF, have been worst hit, as high energy prices make vast swathes of Germany’s manufacturing sector uncompetitive. The self-inflicted economic meltdown in the pursuit of “net zero” policy goals goes beyond Germany. Industrial capacity is being decimated across Europe.

Increasing numbers of European manufacturing companies are shutting down or moving out to countries with cheaper energy supplies such as China and the U.S. Europe’s energy crisis was made worse by the final blow resulting from the loss of cheap piped natural gas after the imposition of the West’s sanctions on Russia after the outbreak of the Ukraine war. Germany’s—and by extension, Europe’s—robust economic growth since the 1960s was predicated on the supply of cheap Russian natural gas supply.

The Green Backlash In Europe

The heavy costs of suppressing the use of fossil fuels while promoting intermittent, weather-dependent renewable energy technologies over the past decade has been disguised and diffused by hidden costs and fiscal transfers to powerful constituencies. But over time, “net zero” climate policies have become increasingly unbearable for ordinary people as they reach beyond the power sector to cover agriculture, transport, homes, and buildings.

Since the summer of 2023, Europe’s Green Deal has been on regulatory pause, as EU governments face a “greenlash” against environmental policies. In the face of energy and cost of living crises, farmers, consumers and trade groups are starting to resent the burdensome costs of sprawling environmental regulations across the continent. Nowhere is this sense of grievance more apparent than in the great European farmer’s revolt, as farmers’ protests escalated across the continent since they first started in the Netherlands in October 2019.

The latest example of the green backlash comes from Scotland. First Minister Humza Yousaf felt compelled to resign last week when the Green party threatened a no-confidence vote in Yousaf’s coalition government. Scottish Green Party co-leader Patrick Harvie said things had “come to a head” after the Scottish government scrapped its target to cut greenhouse gases by 75% by 2030. The First Minister admitted last month that his government was scrapping the policy promises to cut Scotland’s carbon emissions by 75% by 2030 after experts warned it was unachievable.

According to the European Council on Foreign Relation’s European Parliament election forecast published in January, the 2024 election in June could see a major shift to the right in many countries, with populist parties gaining votes and seats across the EU, and centre-left and green parties losing out. The forecast predicted that “anti-European populists were likely to win the largest number of votes in nine member states (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia) and come second or third in nine more countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden).”

As matters come to a head in the run-up to the June European Parliament elections, the co-leader of the Greens group of members in the parliament Mr. Philippe Lamberts recently warned that Europe’s Green Deal “is at high risk of being killed off.” Parties such as the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Sweden Democrats, the Netherland’s Party for Freedom (PVV

Vanguard Large-Cap ETF

The Real World Strikes Back: Corporate America

It is now widely apparent that European governments have been either pausing or cycling back the many environmental rules and regulations in response to the populist backlash against radical climate policies adopted over the past two decades.

But, on the other side of the Atlantic, there is no let-up in the U.S. government’s “whole of government” push for aggressive net-zero policies as the White House renews “discussions about potentially declaring a national climate emergency. ” In its latest announcement on April 25th, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed rules that “will effectively force coal plants to shut down while banning new natural-gas plants” by 2032.

In contrast, corporate America seems to have had a turnaround in its views of the Biden administration’s climate policies. In his annual letter to shareholders last month, JPMorgan’s CEO Jamie Dimon said in reference to the recent cancellation of export permits for LNG projects: “The projects were delayed mainly for political reasons — to pacify those who believe that gas is bad and that oil and gas projects should simply be stopped. This is not only wrong but also enormously naïve.”

This is quite a turnaround for Mr. Dimon who, in his previous annual letter to shareholders, suggested that the U.S. government and climate conscious corporations may have to seize citizen’s private property to enact climate initiatives. He had declared that “governments, businesses and non-governmental organizations” may need to invoke “eminent domain” in order to get the “adequate investments fast enough for grid, solar, wind and pipeline initiatives.”

Mr. Dimon is not alone in pivoting away from a climate focus in investment strategies. Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock

BlackRock

The outlook for uncommon common sense in energy policy in Europe and the U.S. now depends on the outcomes of elections in both places, in June and November respectively. For a deindustrializing Europe, it might be rather late in the day but for the far more robust U.S. economy, it might just be in time before real damage is done.