Central bank digital currency is turning into a pre-occupation of central banks and much of the fintech world. Hundreds of pages of analysis have been produced in the last eighteen months. However, the concept dates back almost three decades and has so far had little impact on the world. So, what are the essential questions about CBDC that need to be answered?

1. What is it?

Money exists in many forms. Two of the most important, banknotes and central bank reserves are created (with a few exceptions in the case of banknotes such as Scotland and Hong Kong) by central banks. Though banknotes are physical and central bank reserves (the balances commercial banks deposit at central banks) are digital, they are economically equivalent. Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) is intended as another form of central bank money, digital like reserves but available to as wide a range of users as physical cash, for both retail and wholesale users. However, potential wholesale users typically have reserve accounts and access to market infrastructure that allows settlement using reserves. This makes the difference between reserves and wholesale CBDC more subtle than that between notes and retail CBDC.

2. Why the sudden interest?

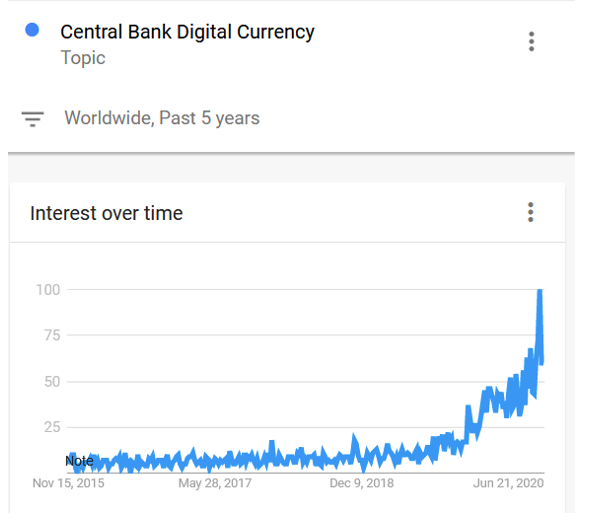

Over the last eighteen months there has been an outpouring of papers about CDBC from major central banks, multinational organisations and consultancies. Not to mention a great deal of discussion in conventional and social media.

Figure 1. Searches on Google

Source: Google Trends

The announcement of Facebook’s proposed digital currency, Libra, in 2019 was a major driver of interest. In his book “Libra Shrugged”, cryptocurrency expert David Gerard described the central banks’ reactions.

“Libra frightened the central banks – a popular private currency run by people who didn’t seem to know what they were doing could prove disastrous. Central banks started looking into CBDC with more urgency. There might be a gap in the market, for low-cost international settlement – and Facebook said Libra could fill that need. But Libra would run at a large enough scale to risk financial stability.”

Progress by People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in implementing a CBDC has also been a major driver of interest. In October 2019 Mark Zuckerberg (CEO of Facebook) warned a House of Representatives committee of the potential consequences of Chinese innovation in the area.

“..I also hope we can talk about the risks of not innovating. While we debate these issues, the rest of the world isn’t waiting. China is moving quickly to launch similar ideas in the coming months. Libra will be backed mostly by dollars and I believe it will extend America’s financial leadership as well as our democratic values and oversight around the world. If America doesn’t innovate, our financial leadership is not guaranteed.” (See here.)

3. What problems does it solve?

CBDC has been proposed as the solution to problems ranging from the hygienic to macroeconomic.

- The risk of spreading Covid-19 and other infectious diseases on banknotes

- The role of physical cash in supporting the black economy

- Lack of financial inclusion

- Limitations on the ability to deal with lack of demand in the economy by techniques such as “air dropping” money to a whole nation or imposing negative interest rates

- Delays in the introduction of technologies based on “Smart Contracts” or Distributed Ledger Technology (aka Blockchain).

However, CBDC is not the unique solution to any of these problems and it is not even obvious why CBDC is the best alternative. Replacing physical cash is increasingly unnecessary in most developed countries. In Sweden the proportion of people using physical cash had fallen to only 13% by 2018. Even in developing nations such as the People’s Republic of China, cash usage has collapsed as people turn to smart phone apps. Going further and fully eliminating cash to control the black economy requires imposing an outright ban on all forms of physical cash (including foreign currencies).

Increasing financial inclusion, airdrops and negative interest rates, also do not require a CBDC. There are alternatives such as giving all unbanked residents access to free basic bank accounts. The fundamental enablers of both low-cost bank accounts and CBDC are the same: A robust method of electronic identity, a method of storing account balances and some form of payments infrastructure.

Sometimes the problems may not be worth solving. Creating CBDC to make it easier to support blockchain based systems makes very strong assumptions about the intrinsic benefits of blockchain.

4. Are there real-life examples?

CBDC is not new. There have been multiple attempts at introducing CBDC. One of the first was the Bank of Finland’s Avant system in 1992. Avant was aimed at small scale retail payments and operated as a pre-paid stored value card. After only three years it was transferred to private ownership and technically stopped being CBDC. A more recent example was Ecuador’s Sistema de Dinero Electrónico in 2014. Unfortunately, it was born with a trust problem. Currency depreciations and financial crises had lead Ecuador to replace its currency with the US dollar in 2000. Dinero Electrónico required Ecuadorians to trust their state to keep electronic dollars fully backed by real dollars. The trust never materialised and the system was shut down in 2018.

2020 saw the launch of PROJECT BAKONG by the National Bank of Cambodia. It has features that resemble a conventional payments system rather than a CBDC such as incorporating the existing Cambodia faster payments system “FAST” and requiring banks to have central bank settlement accounts. The lessons to be learned from Bakong are likely to be very specific for Cambodia because one of the key objectives of the project was to encourage greater use of the local currency as opposed to the US dollar.

5. Does a CBDC need a Blockchain?

The simple answer to this question is “No”. Neither Avant nor Dinero Electrónico used blockchain. Bakong used a form of blockchain called Hyperledger Iroha. The sole role of blockchain in Bakong according to the white paper is to record processed transactions on a centralised permissioned ledger. A role that could be performed by many other technologies.

6. Are CBDCs good news for cryptocurrencies and blockchain?

Blockchain and cryptocurrency enthusiasts are quick to make the link between CBDCs and cryptocurrencies. Central bank proofs of concept demonstrated that elements of blockchain type technology could be included in the implementation of CBDC but did not demonstrate why blockchain was needed. The potential for interoperable CBDCs to be used for international payments further undermines the claims that cryptocurrencies can be a tool for cheaper international payments. Claims that are already very weak.

7. Does CBDC create any problems?

CDBCs potentially create a number of problems. A fundamental risk is of accelerated bank runs. The Bank of Bahamas CBDC, the “Sand Dollar” has specific safeguards built in to stop this happening including limits on the size of deposits and monitoring the liquidity of banks. Another major concern is privacy. CBDC makes it easier for governments to view transactions. However, most governments can already access records of financial transactions. Though in countries with rule of law a court order is usually required. The real threat to the privacy of using physical cash comes if introducing CBDC is combined with bans on physical cash.

8. What are the really big questions?

One of the “horror stories” told about a Chinese CBDC is that it will allow the Chinese Yuan to replace the US dollar as the main reserve currency and allow China to dominate international finance. This misses some fundamental points. The growth of the Yuan’s importance goes in hand with the growth in importance of the Chinese economy, already larger in purchasing parity terms than the US. The Dollar ultimately superseded Sterling because the US economy was considerably larger and more powerful than the Sterling bloc of nations. The other factor of course is the convertibility of the Yuan, a matter of economic policy rather than a technology.

The other big question is whether CBDC will disintermediate commercial banks. Fundamentally this is another policy issue that is not related to technology. The concept of “Narrow Banking” i.e. limiting the ability of the banks to create credit has been in discussion since the Chicago plan of the 1930s. CBDC does not push the direction of this debate in any particular direction.

9. Do we really need CBDC?

Creating CBDCs because of fear of Facebook or China is not a sensible basis for central bank policy. Neither is the desire to innovative for the sake of innovation. CBDCs have either failed or are in the very early days of adoption. A sensible approach determining whether to adopt is to consider the problems that need to be solved (which are often country specific) and the wider range of successful technologies available in the payments area that could achieve the same ends.

The author acknowledges Pan Ng’s assistance in editing.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of the Center for Evidence-Based Management, LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by vjkombajn, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Martin C. W. Walker is director of banking and finance at the Center for Evidence-Based Management. He has published two books and several papers on banking technology. Previous roles include global head of securities finance IT at Dresdner Kleinwort and global head of prime brokerage technology at RBS Markets. He received his master’s degree in computing science from Imperial College, London and his bachelor’s degree in economics from LSE

Martin C. W. Walker is director of banking and finance at the Center for Evidence-Based Management. He has published two books and several papers on banking technology. Previous roles include global head of securities finance IT at Dresdner Kleinwort and global head of prime brokerage technology at RBS Markets. He received his master’s degree in computing science from Imperial College, London and his bachelor’s degree in economics from LSE