A reader asks:

I have recently shifted a substantial portion of the cash portion of my savings into 3-4 month T-bills to take advantage of higher yields and state tax advantages. As of today, they are all set to mature in June and July. I know a US debt default is highly unlikely, but the risk-averse part of me is still a little nervous about what would happen if Congress actually lets the unthinkable happen. Are my worries misplaced? What would happen to my Treasury investments if a default did happen?

Not exactly going out on a limb here but I’m not a fan of the debt ceiling debates we get once every few years now.

We can literally print our own currency. This is why any comparison of the U.S. government to a household budget is willfully ignorant.

I understand the politicians do this to make themselves look important but it’s an unnecessary “crisis” to put us all through.

Everyone is incentivized to get a deal done but you never know with these things.

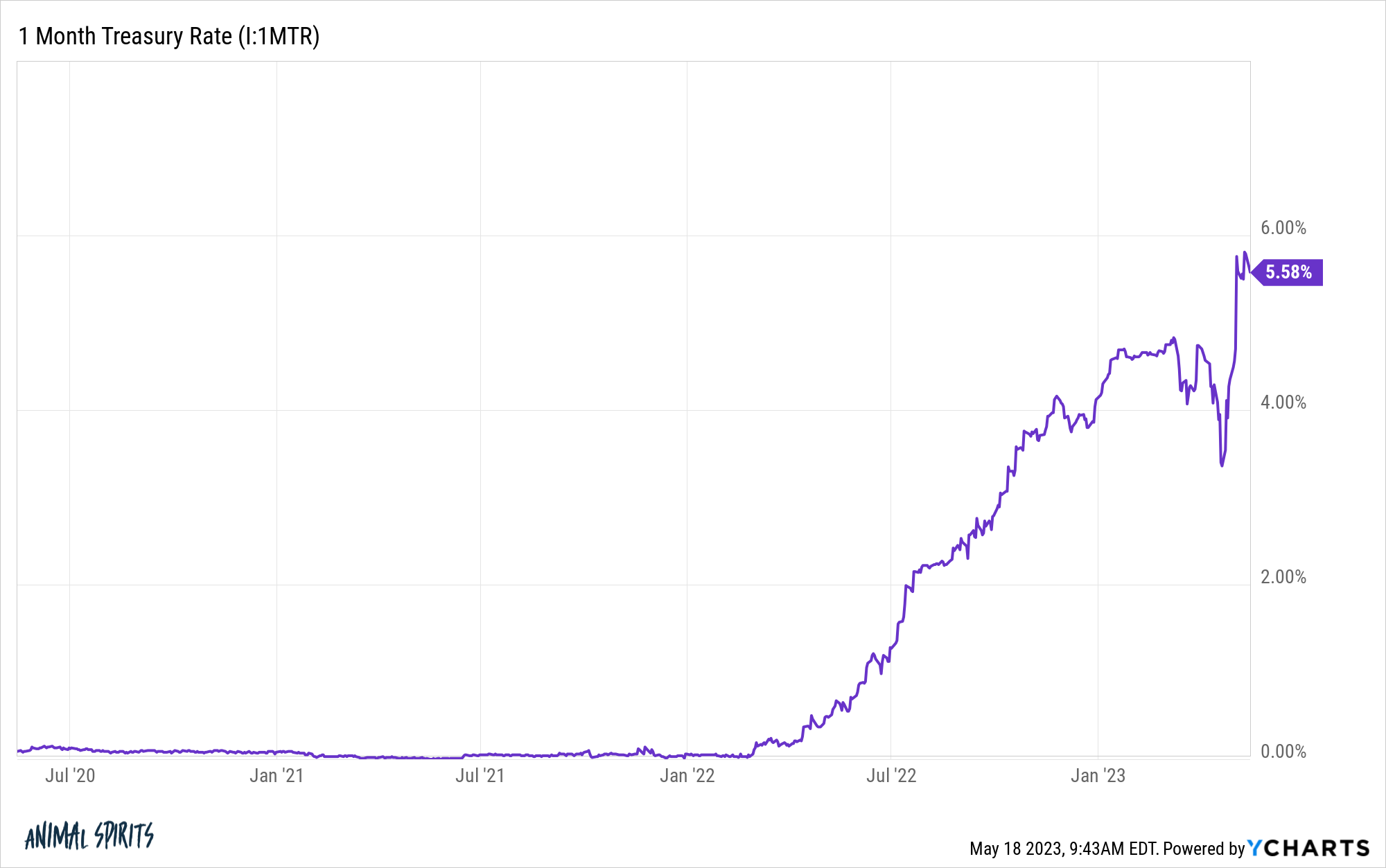

There hasn’t been a whole lot of market volatility surrounding the debt ceiling debate just yet save for one area of the bond market — 1-month T-bills:

At the beginning of April, yields were around 4.75%. Over the next 3 weeks, they dropped like a rock, falling to 3.3%.

Since the end of April, 1-month yields have taken off like a rocket ship, going from 3.3% to 5.6% in less than a month.

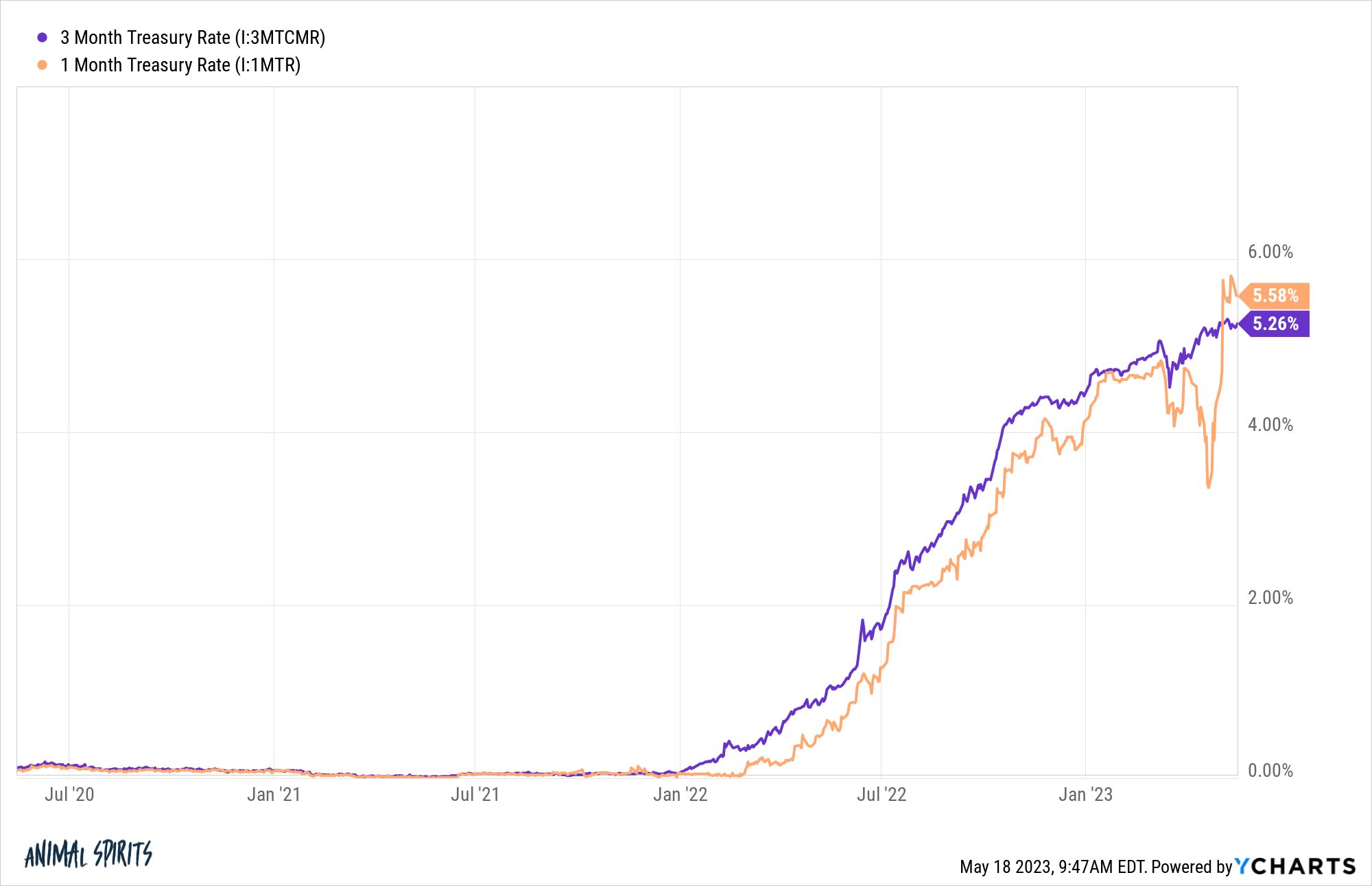

If we look at 3-month T-bill yields you won’t see nearly as much movement of late:

There has been much more volatility in 1-month yields relative to 3-month yields. Three-month yields have also been higher than 1-month yields during this entire hiking cycle…until recent weeks that is.

So what’s going on here?

Positioning is the easy answer. Bond traders are obviously a tad concerned about the possibility of a missed payment from the government on their short-term paper. So investors have been selling 1-month T-bills which has caused rates to move higher in a hurry.

I understand why investors in short-term T-bills are preparing for this risk, even if it seems like a low probability event.

However, I have a hard time seeing the U.S. government miss a payment on its debts.

Cullen Roche detailed some of the moves the government could make if a deal is not struck in time:

I don’t even think you get to the crisis scenario because the Treasury, President and Fed have tools to work around this and I think they’d be obligated to use these tools. For instance, let’s say we get to May 31st and the Treasury announces it has no money on June 1st. Meanwhile Congress can’t agree on anything. In this case the President is forced to invoke the 14th Amendment on May 31st to uphold the “full faith and credit of the USA”. Once we are on the verge of defaulting we’re breaching the 14th amendment, which states that it’s illegal to default. And regardless of the interpretation of these laws there are many ways to fund the Treasury without Congressional approval. This could include issuing premium bonds, coin seigniorage, selling Treasury assets or the Fed invoking the Exigent Circumstances clause of the Federal Reserve Act to directly (or indirectly) fund the Treasury. I am virtually certain that one or all of these would be utilized to avoid an actual default.

I’m sure there are plenty of contingency plans on the table right now.

But if this is something that worries you so much you could always extend your time horizon.

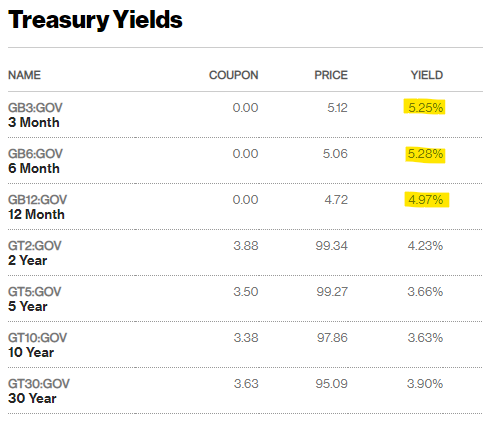

Yields on 6 and 12-month T-bills aren’t that much lower than 1 and 3-month yields.

Another reader asks:

We are mid 30s; kiddo is 2 years old. Kids are expensive so we have to leave the city. Looking to buy a house in the next year or so. How do we slowly sell out of our brokerage accounts so we aren’t at the whims of the market if it crashes during the debt ceiling situation? I’m worried the market might tank and we would be forced to wait until the market rebounds to buy. However, selling and paying the taxes next year won’t be fun either (plus all the other expenses that come with moving).

At face value, this sounds like another debt ceiling question.

It’s not.

This is an asset allocation, risk profile and time horizon question.

Everyone has different risk preferences when it comes to funding their goals.

I invest heavily in equities as a long-term investor. I have a very high tolerance for risk when it comes to assets that are invested for 5, 10, 15, or 20+ years into the future.

But when it comes to short and intermediate-term goals, I am extremely risk averse.

If I need the money in less than a year I don’t like the idea of putting that money to work in the stock market.

The downside risks far outweigh any upside appreciation you could squeeze out in that amount of time. And that downside could come from debt ceiling drama, a recession, a flash crash, the Fed, inflation or any number of other risks we’re not even thinking about right now.

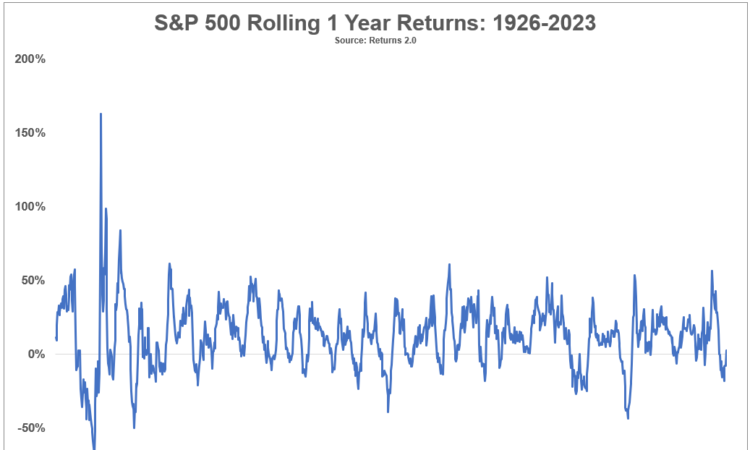

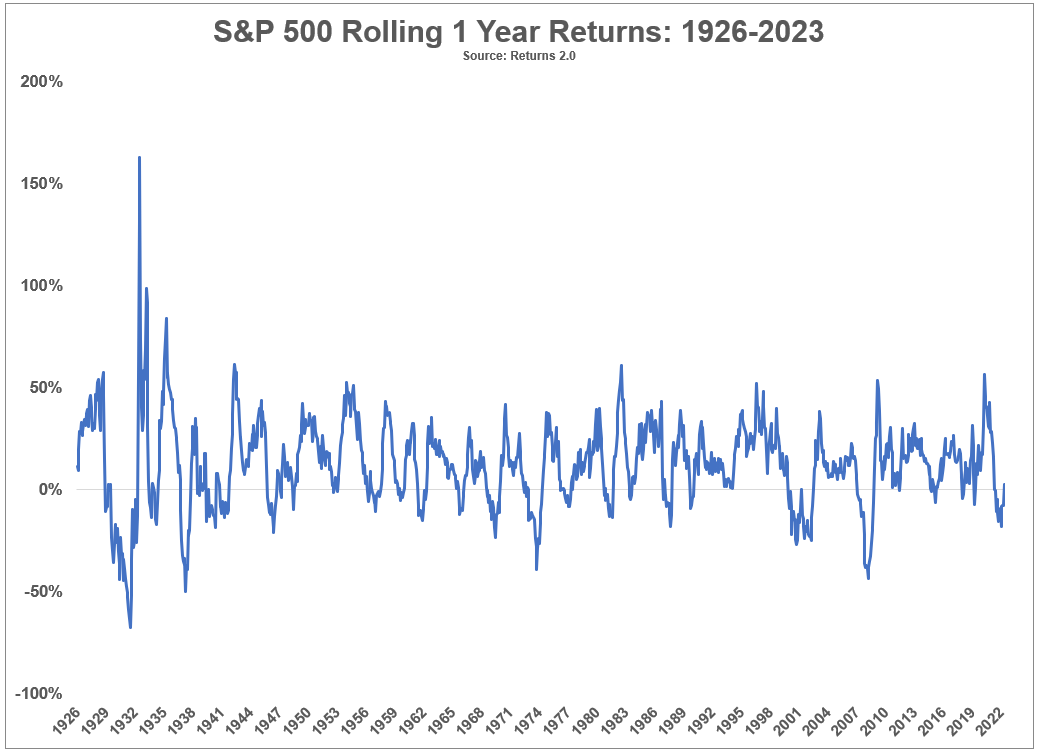

Here are the rolling one year returns for the S&P 500 going back to 1926:

Sure, on average, the stock market has been up around 75% of the time on a one year basis over the past 100 years or so. That’s a pretty good hit rate.

But a 1 out of 4 chance of loss is still way too risky when thinking about something as important as a house downpayment.

Plus, when the stock market does fall, it tends to do so in spectacular fashion.

When stocks were down over these same rolling one year returns:

- they were down 10% or worse more than 52% of the time.

- they were down 20% or worse 24% of the time.

- they were down 30% or worse 12% of the time.

If I was shopping for a house right now I wouldn’t be worried about the debt ceiling or tax payments. I would be worried my cash will be there for a down payment when I needed it.

Let’s say you have $100k saved up for a 20% down payment on a $500k house.

If the stock market falls 10% over the next year you now have $90k.

If the stock market falls 20% over the next year you now have $80k.

Buying a house is stressful enough right now without having to worry coming up with extra money at the worst possible moment.

Sure you could make money but you have to weigh the different regrets here.

Is an extra $5k, $10k or $20k going to move the needle if stocks take off from here?

How painful would it be if you were down $5k, $10k or $20k when you need the money?

You’re right to worry about short-term stock market volatility but the reason itself doesn’t matter. It could be a default or something else.

Funding a goal a year out is way too risky for the stock market.

We discussed both of these questions on the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

Alex Palumbo joined me again this week to answer questions about teaching young people about money, portfolio withdrawal strategies and concentrated portfolios.

Podcast version here: