utah778

Dear Fellow Shareholders,

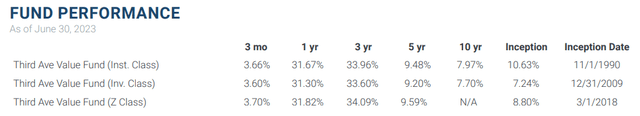

For the three months ended June 30th, 2023, the Third Avenue Value Fund (MUTF:TAVFX, MUTF:TVFVX, MUTF:TAVZX) (the “Fund”) returned 3.66%, as compared to the MSCI World Index1, which returned 7.00%. For further comparison, the MSCI World Value Index2 returned 3.30% during the quarter. This quarter’s positive performance brings the Fund’s year-to-date performance to 12.66%, certainly a strong semester in an absolute sense, albeit one in which Fund performance trailed the 15.43% first-half performance of the MSCI World Index.

During the first half of 2023, large-cap stocks radically outperformed smaller capitalization stocks. For example, the Russell 1000 Index3 (large-cap) outperformed the Russell 2000 Index4 (small-cap) by 8.61%. This phenomenon was not exclusive to U.S. equity markets, as the MSCI World ex US Large-Cap Index5 outperformed the MSCI World ex US Small-Cap Index6 by 6.50%. Through this lens, global equity markets in 2023 have resembled the heady growth bubble days of 2020 much more closely than they have resembled last year’s broad equity market correction. Additionally, as you have almost certainly read, the “breadth” of index returns was extremely low with an unusually large portion of index returns driven by a handful of mega-cap companies, several of which carry some association with artificial intelligence. One manifestation is that the S&P 500 Index, a market-cap weighted index, outperformed the equal-weighted version of itself by almost 10%. All of this has led to large-cap indices recuperating a majority of 2022’s losses.

To the extent that U.S. equity market participants are becoming increasingly assured that the worst of the valuation correction for U.S. large-cap growth equities is behind us and are emboldened by the Nasdaq 100 Index7 rallying 42% from December 2022 lows, outperforming the S&P 5008 by 24% over that period, we offer some cautionary perspective. Our strong suspicion is that the probability of a lasting continuance of large-cap growth stock outperformance is pretty low. That opinion is influenced by: a) current U.S. equity market valuations, as compared to guideposts of historical equity market valuations, b) the unusually high current valuation of U.S. growth equities relative to other cheaper equities, c) the current valuation of U.S. large-caps relative to small-caps, and d) the historical perspective that, while a 42% Nasdaq 100 Index rally and substantial outperformance can certainly appear to have a lot of conviction and causality behind it, both rallies and outperformance of that magnitude are commonplace, even in the midst of a once-in-a-decade type of correction. During the incredibly destructive correction that occurred after the preceding U.S. tech bubble, which peaked in March 2000, the Nasdaq 100 Index produced rallies of 35%, 41%, and 44%, outperforming the S&P 500 Index by 25%, 22%, and 23%, respectively, during those periods. All three rallies occurred in the context of the 31-month correction, during which the Nasdaq 100 Index produced a total loss of 78%, underperforming the S&P 500 by 35%. Put more simply, and less numerically, we encourage readers not to get carried away by great stories and momentum. The price you pay for an investment very likely still matters.

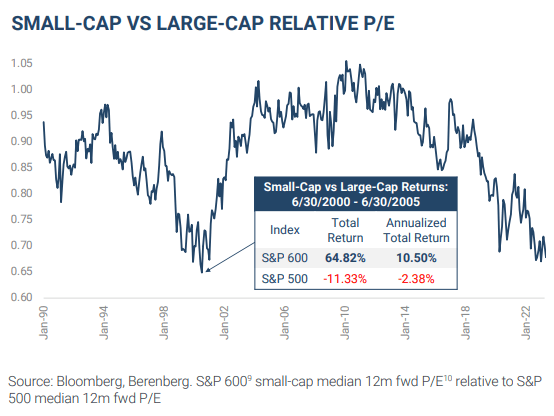

To conclude on this subject, the furtherance of recent years’ underperformance by smaller-cap companies has caused a widening of the already unusually large valuation differential between large companies and smaller companies. Today, the level of small-cap relative undervaluation looks, to us, like a generational opportunity for future small-cap relative outperformance. It would not be unreasonable for you to ask what trigger might set the forces of reconciliation in motion, but anything we might offer as to timing would be insincere. We deal in probable outcomes, but not specific timelines. The current state of affairs simply appears very unusual and unlikely to persist indefinitely. Lastly, while we can’t offer predictions as to timing, we can offer one more significant historical observation. The relative valuation of U.S. small-caps, compared to U.S. large-caps, at the present moment has only been rivalled in one other period during the last 30 years, namely during the late 1990s. Once that extreme condition began to normalize, U.S. small caps produced almost 13% annualized outperformance, versus large caps, over the following five years.

INFLATION, DEBT & SHORTAGES

In order to speak clearly about inflation, one must first specify whether the discussion pertains to actual economic inflation or statistical estimates of inflation, such as the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) or Personal Consumption Expenditure Index (“PCE”). As we have discussed in numerous shareholder letters, particularly the section of our March 21st, 2021 letter titled The Specter of Inflation – Revisited, the statistical methodologies utilized in the calculation of CPI create some substantial time lags through which “real world” developments can appear within statistical data a good bit after the fact. The Shelter component of CPI, as it is known at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”), is a lightning rod for this type of criticism.

That said, the Shelter component of CPI does correlate very strongly to various rent indices, such as CoreLogic Single-Family Rent Index and the Zillow Rent Index, albeit with a lag of about nine months. This lagging property made it clear in March 2021 – when credible rent indices, which measure leading-edge rents, were rising by high-teens percentages on a year-over-year basis – that six to twelve months in the future there would be considerable upward pressure on inflation statistics. Conversely, today’s asking rents have cooled considerably with several leading-edge rent indices suggesting low single-digit year-over-year growth of rental rates, while others are approaching zero. Yet, CPI Shelter data today continues to show shelter costs rising by roughly 8% year over year due to the statistical lag. Why is this important? If one does a quick bit of math, it is clear that the 8% year-over-year increase for the Shelter component of CPI, which comprises 34.5% of CPI by weight, contributed approximately 2.75% of the 4% headline CPI inflation in the most recent month. While we are not suggesting that the Shelter component of CPI will come down to zero in the near term, it does seem very reasonable to expect a substantial amount of downward pressure on headline CPI as we move through the second half of 2023. It is not hard to fathom a scenario in which inflation statistics fall sufficiently close to the Fed’s stated 2% goal to support the arguments of those eager to declare victory in the war on U.S. inflation. To be fair, the Fed has focused more on PCE inflation, which weights Shelter somewhat less heavily than CPI, but the public fixation on CPI still seems to be the focus of public debate.

Furthermore, it’s hard to say what U.S. headline inflation approaching 2% might mean. One outcome might be growing pressure on Fed governors to not only extend the current “pause” but to lower the Fed Funds rate, even though interest rates in the United States today are merely approaching long-term average levels and the macroeconomy is not in any obvious need of support. We don’t particularly understand this logic but we can’t rule it out. Furthermore, implicit in these comments is an “all else being equal condition,” which very well may not hold. There are also “unknown unknowns” we are not even in a position to consider. All of this is to say merely that, even if we are mostly correct about where inflation statistics might be in the short run, the future remains highly uncertain with many potential macroeconomic paths. Finally, and possibly most importantly, we can’t emphasize strongly enough how history shows that capital markets often move in directions that may seem counterintuitive in the context of macroeconomic developments. Steadfast consciousness of this uncertainty strongly discourages us from structuring the Fund’s holdings on the basis of a specific interest rate or macroeconomic view.

As it relates to longer timelines more relevant to our investment approach, regardless of what inflation statistics may appear to show in the latter half of 2023, the jury will still be very much out as to whether broader global inflationary forces have been brought to heel. Over a multi-year time horizon, we continue to see a variety of countervailing economic forces. On one hand, during the protracted global era of virtually free money, a huge amount of cheap debt financing was employed in many areas of finance in order to engineer low returns, offered by overpriced assets and companies, into more respectable leveraged returns. This phenomenon played out across most developed economies. As more and more capital allocators pursued strategies with increasing use of cheap leverage and were richly rewarded for doing so, strategies of that type gained momentum. With more and more capital deployed into leveraged strategies, debt-financeable assets experienced asset price inflation, which produced gains for the asset owners and led to further multiple expansion, which served to compress unlevered returns even further and encouraged the use of even more leverage.

That virtuous cycle for leveraged returns, most obvious in areas such as private equity buyouts and commercial real estate, was enabled not just by a very low cost of debt financing, but by debt costs becoming continuously cheaper. However, that cycle has now been halted and put into reverse. It hasn’t taken long for some overleveraged areas of finance to be exposed by an inability to support the stepped-up cost of huge amounts floating rate debt. Areas with lots of fixed-rate debt may have a delayed reckoning, but unless interest rates fall substantially from here, there will be a lot of reckoning and deleveraging to do as covenants are gradually tripped and maturities roll through the system. It appears very likely that we are just at the beginning of that process. Substantial deleveraging across large swaths of the global economy is likely to act as a strong economic depressant and a deflationary force, as will the negative wealth effect resulting from declining asset values.

However, on the other hand, we also see a number of potentially powerful inflationary forces burbling throughout the global economy. Labor shortages and upward wage pressure are not exclusive to the United States. Tight labor markets and some of the strongest wage gains we have seen in decades feature in several parts of the world today. The U.S. Fed’s focus on cooling the U.S. labor market stems from fear of an upward wage and price spiral, which does not strike us as unreasonable. Meanwhile, U.S. home price affordability statistics fell to the lowest level (least affordable) in about 40 years, as higher interest rates drove mortgage costs materially upward. And yet the combination of incredibly low inventories of existing homes for sale, undersupply of newly built single-family homes, and rising wages has already produced a small upward inflection in the price of U.S. single-family homes. U.S. homebuilders have been reporting shockingly robust demand, given the macroeconomic circumstances. Should upward wage pressure continue, which, all else equal, would lead to gradually improving affordability, it is not inconceivable that we could see home price increases again in coming years, even with elevated financing costs.

Further, we perceive several important commodity markets as having the potential to contribute materially to inflation. Energy market pricing, globally speaking, has been surprisingly weak, in our view, particularly in light of recent inventory draws, the imminent end of U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve releases, and OPEC functioning about as cohesively as it has in recent decades. We perceive financial market participants’ considerable influence over energy futures markets to be a primary cause of separating current pricing from physical market fundamentals. Be that as it may, recent energy market pricing weakness has been an important part of the softening of inflation statistics in recent months. That said, U.S. onshore oil and gas production, which has been by far the world’s largest source of energy production growth over the last decade, essentially adding another Saudi Arabia to the supply equation, has flatlined well below pre-COVID levels. Onshore drilling activity hasn’t recovered anywhere close to 2019 levels and the active U.S. onshore drilling fleet has fallen materially in recent months. We think U.S. oil production has little prospect of recovering to previous highs in the foreseeable future and may even begin to fall based on shrunken levels of investment and drilling activity, along with the gradual maturation of several U.S. oil basins. In the international arena, offshore upstream oil and gas investment remains nearly 40% below the levels of a decade ago. On this last point, even though global offshore investment remains anemic by historical standards, rates for use of the service equipment employed in the investment process – such as drilling rigs, service vessels, subsea installation vessels, etc. – have increased very sharply over the last two years as utilization of that equipment has approached 90% or so, depending on the type of equipment, and demand continues to accelerate. In our view, the probabilities look pretty strongly in favor of growing energy market tightness and increasing cost of production. The potential for energy supply to continue to tighten is broadly important because pricing can, and may, move very sharply upward, and energy pricing filters into the pricing of almost every aspect of the global economy in one way or another.

Similarly, the intersection of looming shortages of absolutely essential industrial metals, such as copper, with government development plans, such as the ironically-named Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S., and a global renewable energy production push, has the potential to proliferate strong inflationary pressures. Also, to the extent near-shoring or friend-shoring of global supply chains begins to gather momentum, one impact would likely be an acceleration of materials-intensive investment, which depends upon access to inputs in limited supply. For example, the United States is structurally undersupplied in cement production capacity, a commodity essential to the construction of infrastructure and buildings of virtually any kind. Today, there is a growing camp of investors and economists beginning to analyze global capital market neglect of industrial production capacity during the most recent decade or two and a broad lack of attention to ensuring the supply of materials.

Whether the deflationary forces of debt reduction or the inflationary forces of shortages ultimately win out, we do not know. It is conceivable that both manifest and a stagflationary environment develops marked by low or no real economic growth along with rising prices. It is also possible that several governments, presiding over some of the world’s largest economies, ultimately come to embrace much higher levels of inflation because it is simply a far more politically expedient way to reduce the burden of indebtedness than raising taxes, cutting spending, and running budget surpluses. Again, we think it is important to consider a wide range of outcomes.

“Now is always the hardest time to invest.” – Bernard Baruch

OUR APPROACH

First, as is hopefully clear from the dissertation above, we are not making specific inflation, interest rate, or macroeconomic predictions and we don’t believe you should either. Capital markets are famous for moving in directions seemingly opposed to macroeconomic developments and we are aware of very few investors who have been able to approach investing on the basis of macroeconomic forecasting and achieve success over multiple cycles. However, during the last few years, equity investors have suffered from a growing obsession with the outlook for interest rates due to the perception that low rates favor fast-growing, low-profit, or no-profit companies, while high rates favor cheaper companies producing profits today. Yet, we believe that history shows this recent relationship between rates and value strategies is contrived and newly minted to rationalize this most recent bubble (See Rates, Ruses & Regime Changes Whitepaper). This relationship is simply not an apparent feature in historical equity markets and it is likely to fade and disappear. In other words, even if one was in a position to make accurate macroeconomic forecasts, predicting capital market reactions to macroeconomic developments is another matter altogether.

Second, a focus on investing in well-capitalized companies has rarely in my multi-decade career seemed more sensible. This has been a pillar of the Third Avenue Management investment approach for more than three decades of operation. In recent years, however, in an environment which bestowed fabulous gains upon those employing evermore cheap debt, this component of our approach may well have acted as a drag on our relative performance. Yet, as the liability side of corporate balance sheets is repriced in a higher interest rate environment, either in the short-term or the medium-term, some of the excessive leveraged risk-taking behavior is likely to be painfully exposed for what it is. On the other hand, companies with excess resources on the asset side of their balance sheets have found themselves in a new regime in which excess cash and securities actually earn meaningful yield and contribute to profit. Further, financial wherewithal not only greatly improves the chances of survival in depressed economic conditions but may also be utilized offensively to build businesses during times of economic stress, as leveraged competitors become weakened or as attractive assets become available for sale by companies needing to reduce indebtedness.

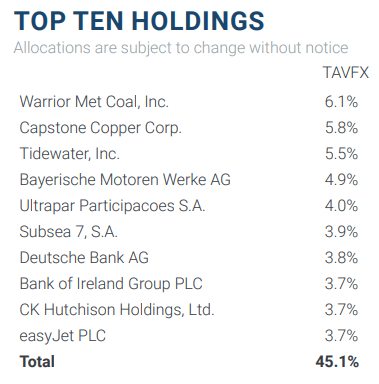

Third, we believe that one of the most important things one can do to protect capital from permanent loss is to avoid overpaying for investments. Overpaying is one of the most significant risks investors of any type face in all operating environments, but I would suggest that the danger is particularly acute and pervasive today. In 2022, the Third Avenue Value Fund produced its strongest year of relative outperformance in 32 years of operation. This was accomplished by building a very cheap portfolio of companies that were, on average, producing very attractive returns relative to our purchase price. As important, however, was the Fund’s avoidance of huge swaths of overpriced U.S. large-cap companies, which performed very poorly during 2022. The first half of 2023 has, in our view, perpetuated an environment marked by rampant overpricing of many U.S. equities. In contrast, as we pointed out earlier in this letter, smaller-capitalization companies look once-in-a-generation-cheap compared to large-cap companies and it would be our expectation that, from this starting position of a very unusual valuation distortion, smaller-cap companies would offer both lower investment risk and higher relative returns, prospectively. We have similarly strong views related to the relative attractiveness of value strategies versus growth strategies and non-U.S. listed companies versus those listed in the U.S. To be very clear, Third Avenue Management does not approach investing from this type of top-down perspective but rather by identifying attractive investment opportunities one at a time from the bottom up. It just so happens that the bulk of the most attractive bottom-up investment opportunities we have been able to identify in recent years happen to corroborate what the top-down view would suggest about areas of relative attractiveness.

Fourth, to the extent that higher levels of inflation develop as a result of the shortages and price pressures, the best way to protect against those pernicious inflationary forces is to own businesses involved in the production of absolutely essential and fundamentally supply-constrained products, provided that can be done at a reasonable price. One bit of good news, as we see it, is that widespread investor neglect of the commodity space over the last decade has left a number of commodity producers and service companies priced inexpensively. In other words, we think copper mining companies are, in general, pretty attractively priced based on today’s metals prices, but see a material looming shortage in coming years. To the extent that labor and natural resources shortages continue to build, pushing inflationary pressure into the broader global economy, it is hard for us to identify a way in which one might be better protected than by owning long-lived mines, producing an absolutely indispensable commodity, that has obvious global supply challenges looming. To the extent that government programs and the energy transition supercharge demand, all the better.

QUARTERLY ACTIVITY

During the quarter ended June 30th, 2023, the Fund initiated a position in HORIBA, Ltd. (“Horiba”) (OTCPK:HRIBF) and exited positions in Dassault Aviation SA (OTCPK:DUAVF) and Daimler Truck Holding AG (OTCPK:DTRUY, OTCPK:DTGHF).

Headquartered in Japan and led for the past three decades by a son of the firm’s founder, Horiba specializes in the measurement and analysis of gases. The company applies this expertise to the development and manufacturing of critical instruments primarily for the semiconductor and automotive industries. Specifically, Horiba produces mass flow controllers (MFC), which are a critical component embedded within the equipment used to make semiconductors. The company has steadily grown market share over the past two decades to the point where it now supplies more than half of all MFCs sold to major semiconductor capital equipment manufacturers. It also has a strong position in other components that go into semiconductor cleaning equipment. The result has been that Horiba’s semiconductor business has been able to grow sales and profits faster than the semiconductor and semiconductor capital equipment industries broadly, over the long-term. By the end of last year, Horiba had already far exceeded its 2023 sales and profitability goals for its semiconductor business set a few years ago. The company’s other major business is the production of emission measurement systems (EMS) for automotive manufacturers. While Horiba has dominant market share in EMS, depressed automotive industry capital expenditures, and Horiba’s own investments in new business lines that have yet to pay off, have led to losses within this segment. A recovery of the operating performance of the automotive business would be highly additive to company profits. Yet, even including the negative contribution from the automotive business, Horiba’s stock trades at a single-digit multiple of consolidated earnings. The company also benefits from the safety of a large net cash position on its balance sheet, which comprises a large percentage of its market capitalization. Horiba’s strong balance sheet and growth in earnings allowed the company to pay an annual dividend in 2022 more than six times larger than the dividend paid ten years ago. Finally, to the extent that the political sensitivity surrounding semiconductors continues to grow, and a reconfiguration of global semiconductor supply chains gains momentum, the construction of new semiconductor fabs will likely entail large orders of new semiconductor capital equipment, many of which would be embedded with Horiba mass flow controllers.

Thank you for your confidence and trust. We look forward to writing again next quarter. In the interim, please do not hesitate to contact us with questions or comments at [email protected].

Sincerely,

Matthew Fine, CFA

1 The MSCI World Index is an unmanaged, free float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index that is designed to measure the equity market performance of 23 of the world’s most developed markets. Source: MSCI.

2 MSCI World Value: The MSCI World Value Index captures large and mid-cap securities exhibiting overall value style characteristics across 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries. The value investment style characteristics for index construction are defined using three variables: book value to price, 12-month forward earnings to price and dividend yield. Source: MSCI

3 The Russell 1000® Index measures the performance of the large-cap segment of the US equity universe. It is a subset of the Russell 3000® Index and includes approximately 1,000 of the largest securities based on a combination of their market cap and current index membership. The Russell 1000 represents approximately 93% of the Russell 3000® Index, as of the most recent reconstitution. The Russell 1000® Index is constructed to provide a comprehensive and unbiased barometer for the large-cap segment and is completely reconstituted annually to ensure new and growing equities are included. Source: FTSE Russell

4 The Russell 1000® Index measures the performance of the large-cap segment of the US equity universe. It is a subset of the Russell 3000® Index and includes approximately 1,000 of the largest securities based on a combination of their market cap and current index membership. The Russell 1000 represents approximately 93% of the Russell 3000® Index, as of the most recent reconstitution. The Russell 1000® Index is constructed to provide a comprehensive and unbiased barometer for the large-cap segment and is completely reconstituted annually to ensure new and growing equities are included. Source: FTSE Russell

5 The MSCI World ex USA Large Cap Index captures large cap representation across 22 of 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries* excluding the US. With 376 constituents, the index covers approximately 70% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country. Source: MSCI

6 The MSCI World ex USA Small Cap Index captures small cap representation across 22 of 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries* (excluding the United States). With 2,489 constituents, the index covers approximately 14% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country. Source: MSCI

7 The NASDAQ-100 Index includes 100 of the largest domestic and international non-financial companies listed on The NASDAQ Stock Market based on market capitalization. The Index reflects companies across major industry groups including computer hardware and software, telecommunications, retail/wholesale trade and biotechnology. Index composition is reviewed on an annual basis in December. Source: Nasdaq

8 S&P 500 Index, or Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, is a market-capitalization-weighted index of 500 leading publicly traded companies in the U.S. Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices

9 S&P 600 Index, or Standard & Poor’s 600 Index seeks to measure the small-cap segment of the U.S. equity market. The index is designed to track companies that meet specific inclusion criteria to ensure that they are liquid and financially viable. Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices

10 Forward price-to-earnings (forward P/E) is a version of the ratio of price-to-earnings (P/E) that uses forecasted earnings for the P/E calculation. While the earnings used in this formula are just an estimate and not as reliable as current or historical earnings data, there are still benefits to estimated P/E analysis.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.