Labour markets are bustling in North America based on April employment data, released last week. US job growth handily beat expectations, whilst Canada is enjoying its longest run of monthly jobs gains since 2017.[i] Considering the two North American nations comprise more than 70% of the developed world stock market, economic trends there receive attention globally.[ii] The April jobs reports are great, but we don’t think it is necessary to draw broader lessons from them—our research has found backward-looking labour data tell you little about future economic conditions or inflation (broadly rising prices across the economy).

In the US, April nonfarm payrolls rose by 253,000 following March’s 165,000 gain, whilst the unemployment rate ticked down from 3.5% to 3.4%.[iii] Hourly earnings—which many observers we follow monitor due to wages’ purported (and misperceived, in our view) connection to inflation—accelerated from March’s 0.3% m/m growth rate to 0.5%, the fastest since March 2022.[iv] Canada’s April Labour Force Survey told a similar story: Total employment rose by 41,000 after March’s 34,000 addition, holding the unemployment rate at 5.0%—unchanged since last December.[v]

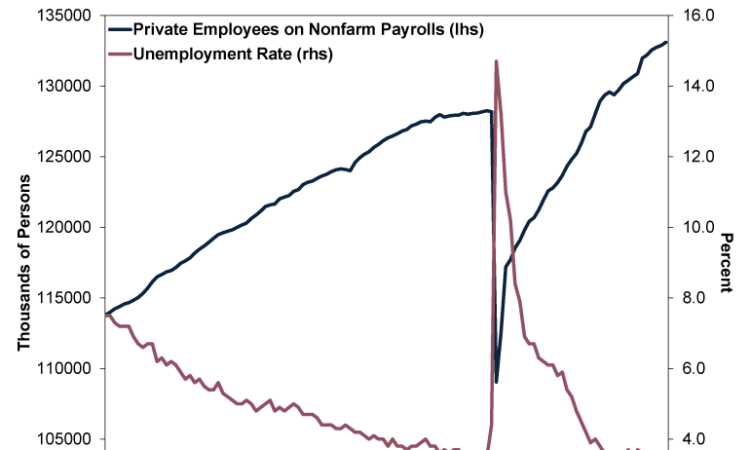

April’s numbers extend recent trends in both nations: Employment levels and the unemployment rate have recovered from the COVID lockdown hit and continue to improve. (Exhibits 1 – 2)

Exhibit 1: A 10-Year Snapshot of the US Labour Market

Source: FactSet, as of 8/5/2023. Private employees on nonfarm payrolls and unemployment rate, monthly, May 2013 – April 2023.

Exhibit 2: A 10-Year Snapshot of the Canadian Labour Market

Source: FactSet, as of 8/5/2023. Total employment and unemployment rate, monthly, May 2013 – April 2023.

We think healthy job markets are a positive, but they are a positive that derives from economic conditions. Said another way, jobs trail economic growth, so the labour market won’t indicate where the economy is going, in our view. In our experience, hiring costs significant time and money, so a company tends to add headcount when it makes business sense to do so (i.e., firms have maxed output and need more workers to meet customer demand). Tied to this, we have found the time and cost it takes for workers to ramp up also means companies typically won’t reduce headcount unless necessary. Accordingly, unemployment tends to rise well after an economic downturn begins. (Exhibits 3 – 4)

We think April hiring in America and Canada confirms past economic growth, but it doesn’t—and can’t—say recession (a broad-based decline in economic activity) is off the table. As Exhibits 3 and 4 illustrate, low unemployment preceded every recession. It didn’t forestall a downturn.

Exhibit 3: US Unemployment Rate, January 1990 – April 2023

Source: FactSet and National Bureau of Economic Research, as of 8/5/2023. Recession dating from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Exhibit 4: Canadian Unemployment Rate, January 1990 – April 2023

Source: FactSet and C.D. Howe Institute, as of 8/5/2023. Recession dating from the C.D. Howe Institute Business Cycle Council.

We have seen experts in America and Canada speculate about how strong jobs data may influence monetary policy, especially since wages in both countries keep rising.[vi] Based on our review of some monetary policy officials’ comments, a common concern is that businesses will pass higher labour costs to customers, keeping inflation elevated—and necessitating further interest rate hikes. But in our view, the critical error in this wage-price spiral theory—as we have seen play out in Japan—is that wage growth follows inflation, not the other way around.

Moreover, monetary policy officials’ actions aren’t predictable according to our research. Entering the year, we noticed plenty of expressed concerns in North America that ongoing rate hikes would weigh on the economy and markets. Then March’s US regional bank scare prompted experts we follow to update their views, with many now anticipating a pause in rate increases. As we wrote last week, maybe that happens—but maybe they keep hiking, too. Consider, too, America’s Labor Department will release its May jobs report before the US Federal Reserve’s next meeting in mid-June. How will those figures influence the Federal Open Market Committee, which makes US monetary policy decisions? Canada won’t have another jobs report before the Bank of Canada’s 7 June meeting, but April inflation comes out next week—and who knows how the latest consumer price data will impact the Governing Council (the Bank of Canada’s policy-making body)?

Rather than getting into the weeds about the potential trickle-down effects of April labour data, we suggest keeping it simple: The latest jobs numbers confirm some past economic growth. We see no need to dig for deeper meaning than that.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 8/5/2023.

[ii] Source: FactSet, as of 11/5/2023. Statement based on the US and Canada’s percentage of the MSCI World Index market capitalisation (a measure of company size calculated by multiplying shares outstanding and current share price), as of 11/5/2023. Whilst America comprises the lion’s share (67.7%), Canada’s 3.4% ranks 5th of the MSCI World’s 23 country constituents.

[vi] Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Statistics Canada, as of 8/5/2023.