“It was a great pleasure to meet with you all and share common views on PNGF opportunity. I here also confirm my availability to support you on this project and provide the best effort to make this dream a reality for all of us.”

With just one email Paul Kionga, the son-in-law of Congolese president Denis Sassou-Nguesso, summed up the story. He sent the message to the executives of Hemla, a Norwegian company, after meeting them in Paris in October 2016. In a few lines, Kionga offered to back their bid for stakes in the PNGF Sud oil field operated by Franco-British giant Perenco.

But the Sassou-Nguesso clan didn’t lend a helping hand for free. When Hemla and Perenco won the lucrative drilling permit in January 2017, the family that rules Congo-Brazzaville with an iron fist made sure they got a slice of the pie.

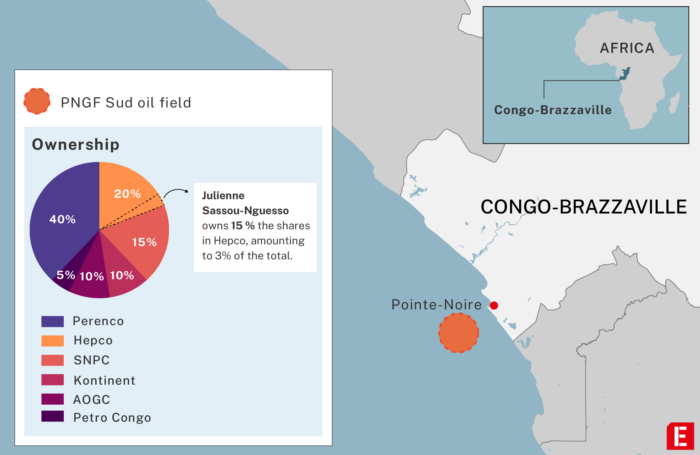

According to sources and documents shared with IE, the president’s daughter, Julienne Sassou-Nguesso, used a string of companies and proxies to secretly acquire 15% of a Hemla subsidiary that got a 20% interest in PNGF Sud. At the same time, Perenco was awarded a 40% stake and operating role.

While Ms Sassou-Nguesso’s name was concealed behind nominees, she was able to reap dividends for years behind the scenes. In 2018 alone she was entitled to at least $3.3 million thanks to her hidden shares in the oil block.

Emails seen by IE also reveal how Kionga, her brother-in-law, and Valentin Tchibota-Goma, a prominent Congolese politician, lobbied the government on behalf of Hemla in late 2016.

At the end of the negotiations, Hemla, Perenco and their local partners paid the Congolese state a one-off $25 million signature bonus for drilling rights, with a further commitment to spend $5 million on local projects. It proved a fruitful investment. In 2021, Hemla’s 20% asset was valued at $212 million in corporate filings, which suggests the PNGF Sud concession could be worth more than $1 billion. In 2017 alone, the company declared an $8.8 million profit in Congo.

“Such scandals should convince European companies to be extra vigilant or to refrain from entering into those business relationships,” Transparency International’s Sara Brimbeuf said in reaction to the findings. “The looting of resources cannot be explained solely by the corruption of oil-producing countries,” she added. “It is the failing of the oil majors’ compliance that allows such practices to flourish.”

Hemla was founded in 2009 by Norwegian businessmen Knut Søvold and Gerhard Ludvigsen. When they entered the Congolese market in 2017, they teamed up with Emirati firm Petromal to create Hepco, their local subsidiary that counts Julienne Sassou-Nguesso as a shadow investor. Between 2019 and 2021 the Norwegian pair and Petromal progressively passed on their Hepco shares to Petronor, another company that mostly belongs to them.

Norway’s authority for fighting economic crimes, Økokrim, detained Søvold and Ludvigsen in December 2021 on suspicion of corruption in Africa. Økokrim told IE that the probe is ongoing but wouldn’t confirm if it is connected to Congo. In April 2022, Petronor announced that Eyas Alhomouz, its current chair and the Petromal chief, was also considered a suspect by both Økokrim and the US Department of Justice, as he is a US citizen. The DoJ declined to comment.

When approached for comment, all three men denied wrongdoing. Alhomouz said he could not add anything because of the Økokrim investigation, but Søvold and Ludvigsen sent a joint statement via their lawyers, in which there was no mention of Julienne Sassou-Nguesso, despite IE’s specific questions about her. They added that comparisons between the signature bonus paid and the current value of stakes in the project were “not meaningful” and that the investment was all above board.

Petronor, which is listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange, refused to comment. The Congolese state and Ms Sassou-Nguesso did not reply to emails sent via their lawyers and the president’s communications team.

Congo-Brazzaville is one of the most corrupt countries in the world with half of its 5.2 million citizens living in extreme poverty. Following a series of coups, Denis Sassou-Nguesso became president in 1979 and has held that office almost uninterrupted since. His authoritarian rule, marked by years of civil war, has muzzled dissidents while filling the pockets of his cronies.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons For years members of Denis Sassou-Nguesso’s family have been accused of siphoning off the nation’s oil revenues. In 2020 US prosecutors alleged that his son, Denis-Christel, stole millions of dollars of state funds to purchase real estate. In 2017, Julienne Sassou-Nguesso was charged with corruption in France in the so-called “ill-gotten gains” affair. Judges have been probing whether she bought a luxury mansion near Paris with misappropriated money in 2006.

An insurance agent by profession, Julienne Sassou-Nguesso was described as “Congo’s most influential woman” by one Congolese oil businessman who spoke to IE on condition of anonymity. “The president can’t refuse her anything,” he said.

Sassou-Nguesso used proxies to get oil shares

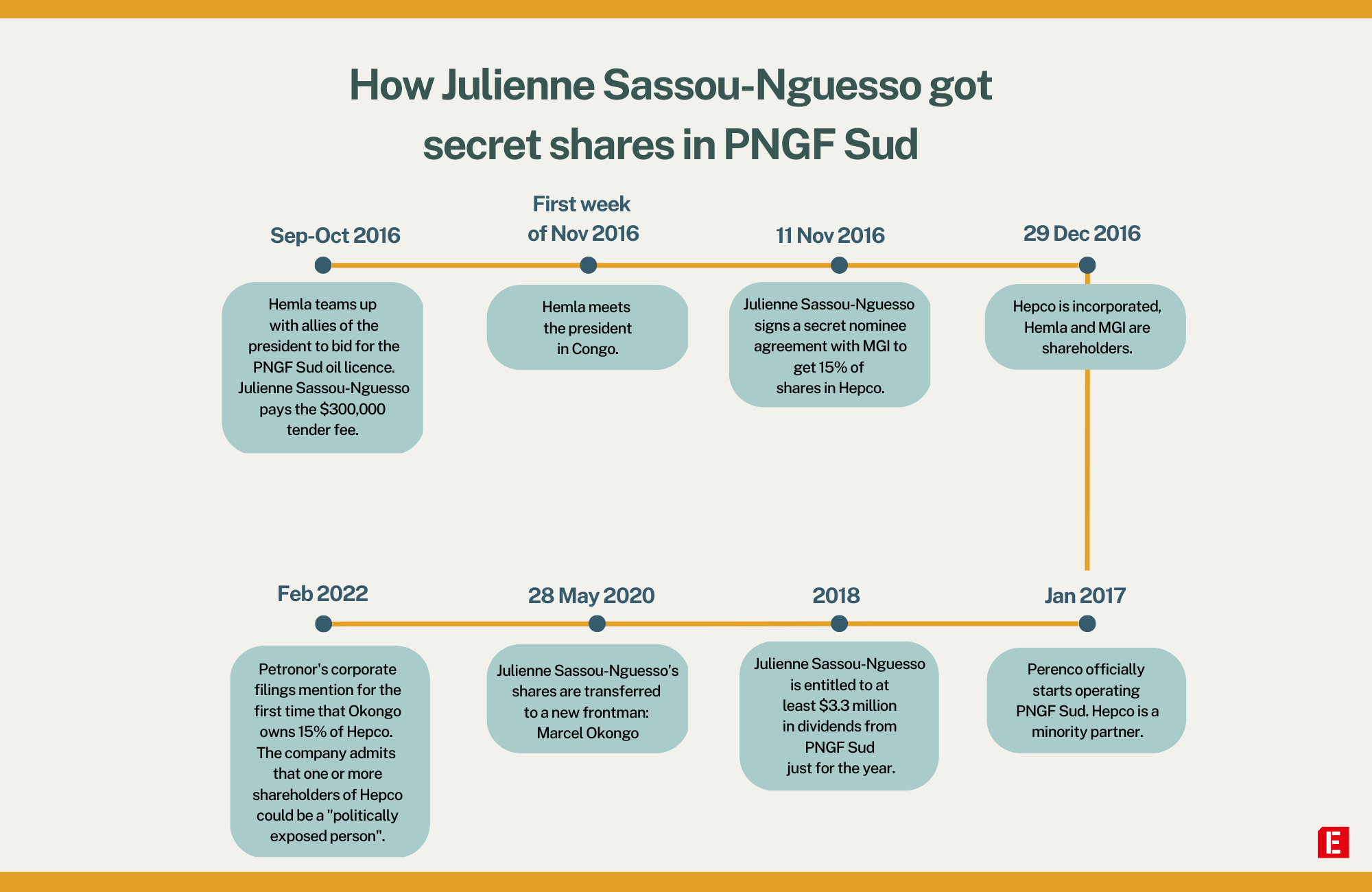

Sources suggest that Ms Sassou-Nguesso got involved in PNGF Sud as early as the autumn of 2016, when she paid the $300,000 tender fee required by the government so that Hemla could enter the bidding process.

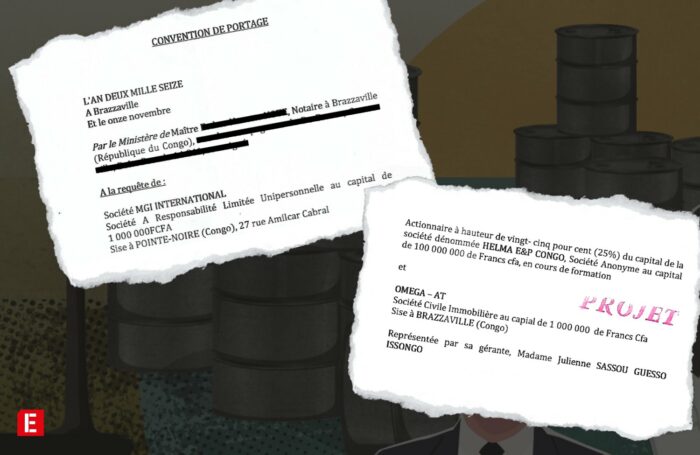

In the first week of November, the president met Ludvigsen and Alhomouz in Congo to discuss their plans for PNGF Sud. Shortly after, on 11 November, Ms Sassou-Nguesso devised a secret pact to enter the capital of Hemla’s new Congolese branch: Hepco.

“Neither Søvold nor Ludvigsen had or has reason to believe that the tender process was in any way compromised,” the pair’s lawyers said. “Such courtesy visits are customary all over the world.”

According to contracts shared with IE, the president’s daughter acquired 15% of Hepco via Omega-AT SCI, one of her real estate companies. To conceal her involvement and ensure her name wouldn’t surface in incorporation deeds, she had a nominee agreement with a second entity managed by allies of the family: MGI International, an oil and trading firm. On paper, MGI was Hemla’s local partner in Congo, owning 25% of Hepco. But in reality, MGI only had 10% of the subsidiary and held Ms Sassou-Nguesso’s 15% on her behalf.

As a result, the president’s daughter never appeared publicly, while MGI was still sending her the dividends of Omega’s share in PNGF Sud, where Perenco has been pumping over 20,000 barrels of oil a day in the Atlantic Ocean. If precautions were taken to hide Ms Sassou-Nguesso’s involvement with Hemla, less care was applied to other partners close to the ruling family.

MGI itself is littered with red flags. One of its top managers is Paul Kionga and the company is reportedly owned by Valentin Tchibota-Goma, the general secretary of the Action and Renewal Movement, a political party in the government majority. Both Tchibota-Goma and Kionga were successively named directors of Hepco in 2017 and 2018, regardless of their conflicts of interests. Neither responded to requests for comment.

For several years, MGI discreetly guarded the ruling family’s interests in PNGF Sud. But a financial dispute between Petronor and its Congolese partner started to draw unwanted attention. In 2018, the Norwegian group listed in its public accounts a $7 million interest-free loan granted to MGI. What could justify such a transactions? Lawyers for Søvold and Ludvigsen said “all business decisions have been taken on a transparent and open basis on commercial terms.”

On this question, like others, Petronor did not reply. But what’s certain is that in February 2021, the group publicly announced that the loan’s conditions had been breached and a Congolese court ruled that the multinational could seize 9.9% of MGI’s shares in Hepco. Still Ms Sassou-Nguesso’s stakes were safe. A contract from 28 May 2020 shows that her shares were transferred from MGI to a new proxy: Marcel Okongo, a cousin of the president and a construction magnate. Sources clearly identified him as a “frontman”.

When Petronor listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange in February 2022, it issued a 390-page prospectus. Several paragraphs detailed how the group clawed back MGI’s shares in Hepco but little was mentioned about the subsidiary’s new shareholder: Marcel Okongo. The name occurred only twice, in very small print. However, by Petronor’s own admittance, “one or more ultimate beneficial shareholders of one of the Company’s subsidiaries, HEPCO, may also be a [politically exposed person].”

‘Congo’s oil sector works like a cartel’

Okongo isn’t the only questionable associate in PNGF Sud. Since 2015, Congolese law means that all new drilling licences must award rights to the state-controlled National Petroleum Company of Congo (SNPC) and private local companies.

So when in 2017 Perenco and Hemla inherited the oil field from its previous owners, French and Italian majors Total and Eni respectively, they had to team up with a handful of local firms linked to controversies in Congo’s oil sector.

The first, SNPC, got a 15% interest in PNGF Sud. Under the heel of the Sassou-Nguesso family and close allies, the national oil company has been cited in various court cases around the world. In 2020, US prosecutors claimed that the president”s son, Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso, embezzled millions of dollars from SNPC to purchase a Miami penthouse.

The second with 10% is Kontinent, a company registered by Yaya Moussa, a former International Monetary Fund envoy to Brazzaville. Just before the IMF granted Congo a nearly $2 billion bailout in 2010, Moussa quit his job and moved to the oil sector.

In 2021, Moussa was identified by Italian prosecutors as “linked to Congolese public officials” as part of a probe into Eni’s permit renewals in Congo. However, no charges were bought against him at the time. A confidential contract shared with IE also shows how Moussa and the Congolese government signed a deal in 2011 so that Kontinent would be paid nearly €700,000 to advise on the rules of future sharing agreements that were enacted in 2015. Simply put, the former IMF employee was asked to contribute to shape laws that allowed him to gain shares in PNGF Sud and other blocks the following years.

Lawyers for Kontinent and Moussa told IE their clients didn’t know about Julienne Sassou Nguesso’s involvement in PNGF Sud. They denied any conflict of interest or business links with the president’s family (read here).

The third, also with 10%, is AOGC, a business founded in 2002 by the former SNPC boss Denis Gokana. The president’s special hydrocarbons advisor, he also serves as a member of parliament. Another firm mostly owned by AOGC, Petro Congo, won a further 5% stake in PNGF Sud.

In 2005, the London High Court described how Gokana embezzled oil money from SNPC, and in 2021, he was labelled by Italian judges as a “corrupt official” following the Eni investigation.

“Congo’s oil sector works like a cartel, all the actors know each other and make super-profits together,” Andrea Ngombet, a Congolese anti-corruption activist told IE. Ngombet, founder of the Paris-based collective Sassoufit, regrets that European multinationals sustain the system. “All the most dubious operators regard Congo as land of plenty,” he said. “They can come with empty pockets and leave as billionaires as long as they’re ready to work as proxies.”

Perenco itself has maintained close ties to powerful local businesses since moving into Congo over two decades ago. Today, the group extracts 85,000 barrels of oil per day in the country. It is in partnerships with AOGC and Petro Congo in two other permits and set up a local firm as a joint venture with SNPC to operate two more.

Perenco declined to comment on the beneficial owners of its Congolese partners but said it identified no risks in working with them. “There are no failures of compliance with regards Perenco’s activities on the PNGF Sud permit,” a spokesperson said, adding that licence shares are allocated directly by the government.

In the next few days, French president Emmanuel Macron will visit his counterpart Denis Sassou-Nguesso in Brazzaville. If the topics of their meeting were not disclosed, it will be hard to avoid discussing oil, which accounts for a third of the country’s GDP and virtually all its exports to France.

Perenco Files is supported by the IJ4EU Investigation Support Scheme.