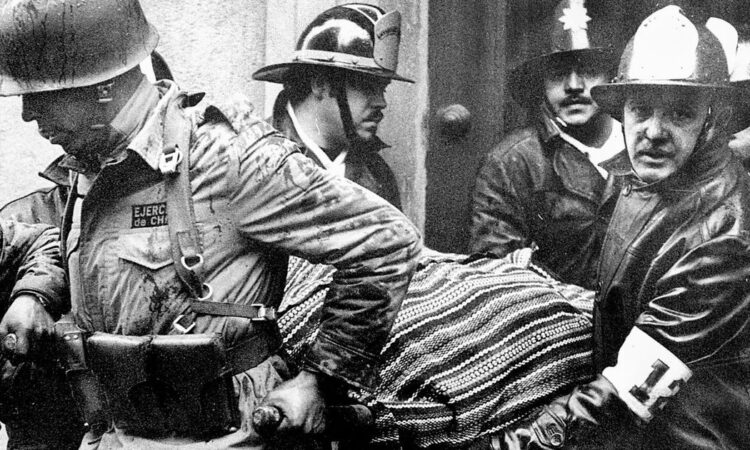

Fifty years ago this Monday, Chilean air force fighter jets strafed the La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago as democratically elected socialist President Salvador Allende delivered a rousing final speech and died by suicide amid the palace’s burning flames.

The coup was particularly tragic because historically Chile was an island of democratic peace in a region too often punctuated by violence and right-wing military coups. It brought an end to one of the longest-standing democracies in Latin America and initiated a 17-year brutal dictatorship headed by Army Gen. Augusto Pinochet that killed over 2,300 people, tortured more than 30,000, and sent tens of thousands into exile.

While U.S. intervention in Chile is documented and acknowledged by virtually all, interpretations of it vary. For the left, the coup illegally unseated a freely elected democratic government, deposed because it threatened U.S. business interests. They often suggested, without concrete evidence, that the Nixon administration and CIA effectively stage-managed the coup. For the right, the coup derailed Allende’s dangerous communist experiment, and U.S. involvement short-circuited Chile’s descent into authoritarianism, providing a bulwark against the spread of communism.

The widespread classification of documents has complicated the understanding of the role of the United States in Chile’s democratic breakdown. Both sides of the ideological debate seized on the trickle of declassified documents released over the years in response to pressures by the National Security Archives, and its Chile specialist, Peter Kornbluh. Still, despite his tireless efforts, many documents potentially central to understanding the role of the U.S. in Chile during the 1960s and 1970s remained classified.

In the lead-up to the 50th anniversary of the coup, Chilean officials formally petitioned the Biden administration for a wider release of documents to help Chileans close this painful chapter in their history. In response, the CIA and State Department released a series of documents two weeks ago that shed new, but not dramatic, light on the extent of U.S. involvement in the coup. Of particular interest to those seeking more transparency were the presidential daily briefs in the days leading up to the coup, which had remained classified for decades.

Previously declassified documents demonstrated that the U.S. undoubtedly helped set the stage for the coup by supporting Allende’s opposition, fomenting strikes, advocating for an invisible economic blockade, and actively intervening in copper markets on which Chile relied for most of its income. Still, the potentially direct role played by the CIA remained unclear. The recently released briefs show that while the Nixon administration knew of and supported a coup, the CIA was not directly involved in its execution. Presidential daily briefs in the days leading up to the coup informed Nixon of the “possibility of an early military coup attempt,” and noted that the military was “determined to restore political and economic order” but still lacked “an effectively coordinated plan that would capitalize on the widespread civilian opposition,” and that there was “no evidence of a coordinated … coup plan.”

Fifty years on Chile is heralded for its relative success in the region in economic and political terms. Throughout the ‘90s, its democratic transition was repeatedly held up as a model for other countries. Today, Chile regularly ranks in the top two most democratic and cleanest countries in Latin America along with Uruguay. Chile is also by far the most successful economy in Latin America, and post-transitional governments made remarkable strides in eliminating extreme poverty, diversifying export markets, and providing widespread access to higher education.

Still, the dictatorship’s economic free market model left Chile as one of the least equal countries in the world, and the health care, education and pension systems regularly fall short in providing all Chileans a dignified existence. A massive and destructive social uprising in 2019 shed light on this growing sense of injustice and inequality. Recent public opinion polls also show an almost universal rejection of Chilean political institutions and its political class.

The near victory of far-right and Pinochet admirer José Antonio Kast in the 2021 presidential elections suggests that Chile is not immune to the type of right-wing populism increasingly common in the world. Finally, the hopeful opportunity that the 2019 uprising provided to do away with the Pinochet-era constitution now seems destined to fail. Despite success, today a sense of democratic precariousness remains in Chile.

U.S. involvement in Chilean politics was just another chapter in the litany of Latin American interventions prompted by Cold War politics. U.S. concern for the region has always responded to its wider strategic interests. Current U.S. interests and the interests of the region now rest firmly with underwriting democracy in the region, but the urgency of supporting democracy has, unfortunately, faded along with the Cold War.

Democracy is not invincible. If anything, the 50th anniversary of Chile’s military coup provides us a moment to reflect on the ever-present fragility of democracy in Chile and around the world and the need to tirelessly defend it against very real threats at home and abroad.

Peter M. Siavelis is professor of politics and international Affairs at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. He is a long-time analyst of Chilean politics and recently co-authored Chile’s Constitutional Chaos in Journal of Democracy and Chile’s Constitutional Moment in Current History. He wrote this column for The Dallas Morning News

Part of our “The Unraveling of Latin America” series. In this column the author discusses recent revelations about the U.S. involvement in one of the darkest chapters in the history of the region: the Chilean coup of 1973.

We welcome your thoughts in a letter to the editor. See the guidelines and submit your letter here. If you have problems with the form, you can submit via email at letters@dallasnews.com