When police shot a teenager dead this week in Paris, a rumbling pressure-cooker of social grievance exploded.

Riots broke out this week in Nanterre, a suburb of Paris, following the lethal police shooting of a 17-year-old boy named as Nahel M. An investigation into his death is continuing but the situation has already triggered protest and anger well beyond. Whatever the investigation concludes, the incident forms part of a complex, deep-rooted problem.

It raises the memory of the violence that spread across the city’s suburbs in 2005, lasting more than three weeks and forcing the country into a state of emergency. Many of the issues behind the unrest back then remain unresolved and have potentially been aggravated by ever-worsening relations between the police and the public.

During my extensive fieldwork in the suburban estates of Paris, Lyon and Marseille I have seen and heard first-hand the grievances now being articulated on the streets of Nanterre.

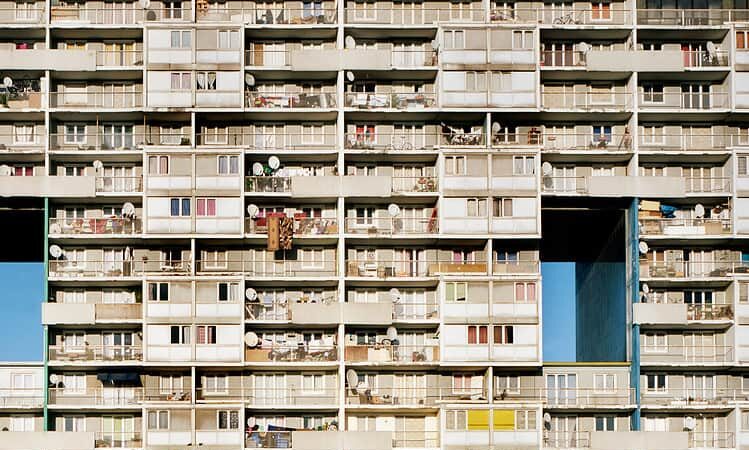

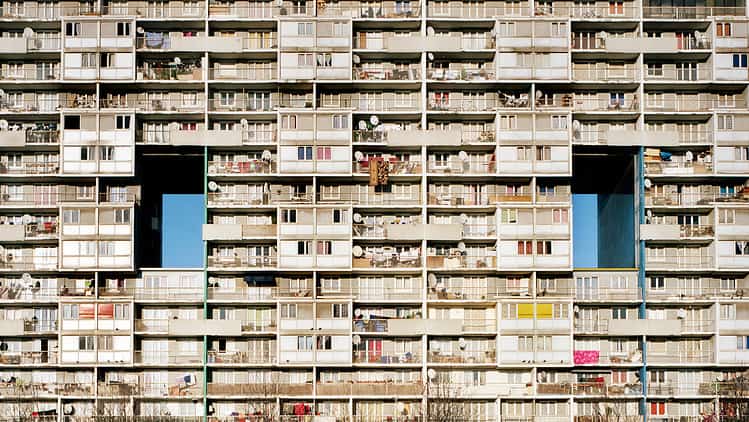

The suburbs and poverty

Certain suburbs of large French cities have, for decades, suffered from what has been labelled the worst ‘hypermarginalisation‘ in Europe. Poor-quality housing and schooling combine with geographical isolation and racism to make it virtually impossible for people to stand a chance at improving their circumstances.

Become part of our Community of Thought Leaders

Get fresh perspectives delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for our newsletter to receive thought-provoking opinion articles and expert analysis on the most pressing political, economic and social issues of our time. Join our community of engaged readers and be a part of the conversation.

Evidence has long shown that people living in poor suburbs can expect to face discrimination based on the very fact of living in those suburbs when they apply for a job. Even just having a certain name on your CV can rule you out of employment thanks to widespread racial discrimination.

Discontent among young people in these places has been brewing for decades as a result. The first riots of the kind currently happening in Paris took place in Lyon as far back as the 1990s. And yet, outside moments of crisis, there appears to be practically no discussion by the French leadership about how to tackle the problems that drive so much anger in the suburbs.

The president, Emmanuel Macron, presents himself as committed to reindustrialising France and revitalising the economy. But his vision does not include any plan for using economic growth to bring opportunity to the suburbs or, viewed the other way round, to harness the potential of the suburbs to drive economic growth. In two presidential terms, he has failed to produce a coherent policy for solving some of their key problems.

Police brutality

Police brutality is a topic of great concern in France at the moment, beyond the Nanterre incident. Earlier this year, the European commissioner for human rights of the Council of Europe took the extraordinary step of lambasting the French police for ‘excessive use of force‘ during protests against Macron’s pension reforms.

Policing appears stuck in an all-or-nothing approach. In a recent interview I helped conduct for a documentary in the suburbs of Marseille, residents pointed to successive cuts to community-based police officers, based in the estates, as key reasons for increases in tension between the population and the police. Protests, meanwhile, are met with tear gas and batons.

Successive governments have used policing to control the population to prevent political turmoil, eroding the legitimacy of law enforcement along the way. And yet, the police are extremely hostile to reform, a stance aided and abetted by their powerful unions and Macron himself, who needs the police to crush opposition to his reforms.

Macron versus Sarkozy

The former president Nicolas Sarkozy is infamous for inflaming tensions during the 2005 riots by referring to the people involved as ‘scum‘ who needed to be pressure-washed from the suburbs. Macron, too, has been repeatedly criticised for striking an arrogant tone during his political career, making numerous gaffes—including suggesting an unemployed worker only needed to ‘cross the street‘ to find work.

His conciliatory response to the death of Nahel could not however be further removed from Sarkozy’s stance. He called the killing ‘inexcusable‘ and held a crisis meeting to seek a solution. A trip to see Elton John perform while the riots occurred was perhaps not advisable and comments about young people being ‘intoxicated’ by video games were somewhat misguided, but Macron has at least tried to calm tensions and not inflame them.

Support Progressive Ideas: Become a Social Europe Member!

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. You can help us create more high-quality articles, podcasts and videos that challenge conventional thinking and foster a more informed and democratic society. Join us in our mission – your support makes all the difference!

A key problem for him, however, is the diffuse, decentralised nature of the protestors. There is no leadership to meet and negotiate with, and there are no specific demands that need to be met to defuse the tension. As in 2005, the riots are occurring spontaneously, sometimes estate by estate.

That makes escalation very difficult for the government to stop. And it underscores the need for a far more wide-reaching, thoughtful response to tackle the entrenched, decades-old problems of poor social prospects and police brutality in the suburbs of French cities.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence