Why the Fed Can Let the Housing Bust Rip: Mortgages, HELOCs, Delinquencies, Foreclosures, and Who’s on the Hook

Mostly taxpayers, not the banks.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

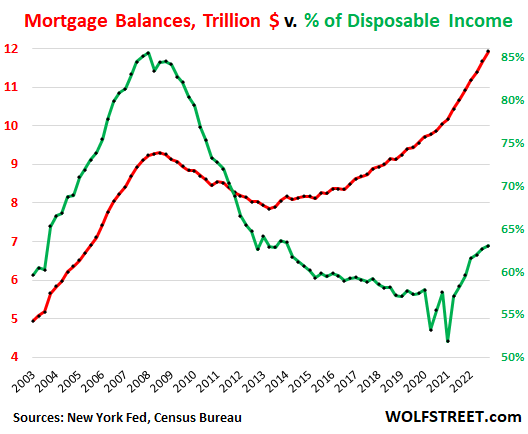

Mortgage balances ballooned because home prices ballooned in recent years, requiring more debt to finance the same home, and so mortgage balances in Q4 rose 2.2%, or by $253 billion, from the prior quarter, and by 9%, or by $1 trillion, from a year earlier, even as home sales volume plunged by 34% in Q4. Mortgage balances now reached $11.9 trillion.

Over the three-year period that covers the Fed’s pandemic-era money-printing binge and interest-rate repression, mortgage balances exploded by 25%, according to the New York Fed’s data on household credit. Over the same period, the median home price ballooned by 34%, according to the National Association of Realtors, even after the 11% drop from the peak in June 2022.

The chart also shows mortgage debt as a percent of disposable income (green), a measure of the aggregate burden of this mortgage debt on households. It shows why the Housing Bust in 2005-2012 was such a mess, and it also shows one of the reasons the same kind of mortgage crisis is now unlikely. But the home-price inflation since 2020 has started leaving its mark on the ratio – after the pandemic monies stopped inflating disposable income:

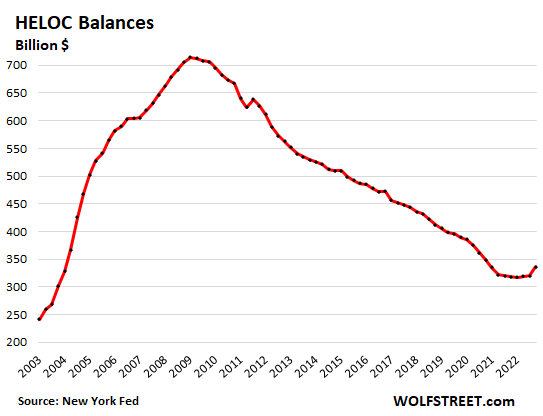

Balances of Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOC) finally ticked up visibly for the first time in years. We’ve been expecting this uptick for a while because cash-out refis stopped making sense when mortgage rates shot higher in 2022. You don’t want to refinance an entire 3% $500,000 mortgage with a 6% $600,000 mortgage. Talk about payment shock! But you could keep the original 3% mortgage and add a 6% HELOC for $100,000, and that would be more manageable.

HELOCs are one of the classic ways to use home equity as an ATM. But cash-out refis at ultra-low interest rates nearly killed the HELOC business. And now it’s coming back in baby steps.

HELOC balances, after creeping along at very low levels since early 2021, rose by 5.0% in Q4 from Q3, or by $16 billion, to $340 billion.

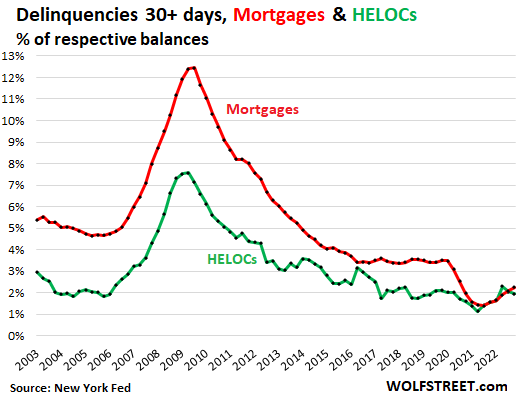

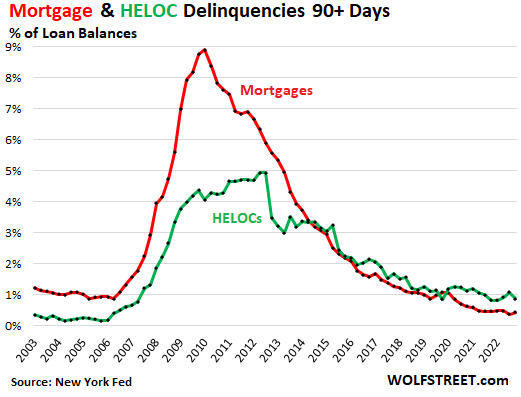

Mortgage and HELOC delinquencies have inched up from historic lows but remain very low.

For mortgages, the 30-day-plus delinquency rate – the rate of borrowers who newly transition into delinquency – ticked up for the third month in a row to 2.3% (red line in the chart below), which was still below any pre-pandemic low in the data going back to 2003.

During the Good Times before Housing Bust 1, in 2005, the delinquency rate bottomed out at 4.6%. During the Good Times before the pandemic, the delinquency rate bottomed out at 3.4%.

The 30-plus-days delinquency rate of HELOCs ticked down for the second month in a row, to 2.0%, right in line with the Good Times:

Balances that transitioned into serious delinquency (90-plus days delinquent) of mortgages and HELOCs remained near historic lows. For mortgages, the 90-plus delinquency rate ticked up to 0.43%, the second-lowest in the data, just above the 0.37% in Q3. During the Good Times, the serious delinquency rate ran at about 1%, and it headed to 9% during the Bad Times.

For HELOCs, seriously delinquent balances dipped in Q4 to 0.9%:

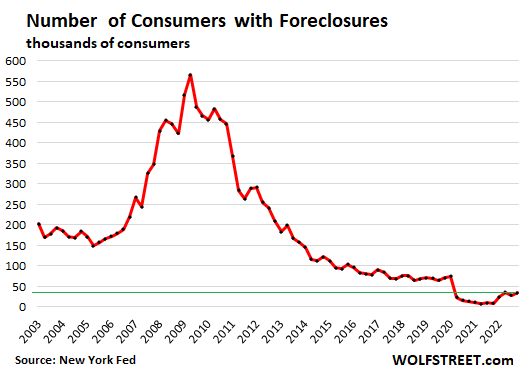

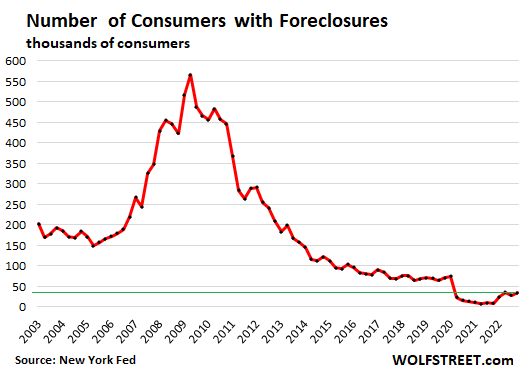

Foreclosures have ticked up from historic lows but remain near historic lows. In Q4, the number of consumers with foreclosures edged up to 34,280, just below Q2.

During the Good Times before the pandemic, there were about 70,000 consumers with foreclosures, more than double the current number. During the Good Times before 2006, at the low point, there were about 150,000 consumers with foreclosures, over four times the current number.

Foreclosures should eventually return to the Good Times normal, they would have to double to get there, which would be normal. But so far, that hasn’t happened yet.

The Fed can let the Housing Bust rip.

The Financial Crisis, which was triggered by the Mortgage Crisis, put the entire US banking system, and thereby the global banking system, at risk, and a big mess ensued. This was kind of a special event.

There may be other special events coming at the US financial system, but it’s unlikely to come from mortgages. This data here tells us that. And the way the mortgage market has been changed since the Financial Crisis also tells us that – because now it’s the taxpayer that is on the hook for much of the mortgage debt, and nearly all of the risky mortgage debt, and not the banks.

The classic consequences on mortgages and mortgage holders that come with a housing bust will therefore remain in the classic range for the private sector – and not enter into the Financial Crisis bloodbath range.

The biggest part of the damage will be absorbed by taxpayers because they’ve been shanghaied into guaranteeing the majority of mortgages that have been securitized into MBS, and into guaranteeing subprime mortgages, and low-down-payment mortgages (via FHA, VA, etc.), and no one cares about the taxpayer anymore, not even the taxpayers themselves.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()