The selloff in government bonds in recent days is being called the “one of the most violent recalibrations” of the bond market in recent years, and the shock waves are being felt around the world.

What is happening?

The rout has pushed long-term borrowing costs to its highest level in more than a decade, with the yield on 30-year U.S. Treasuries on Oct. 4 breaching five per cent for the first time since 2007. When a bond yield rises, its price falls.

It’s the speed of the selloff that is unnerving, and the volatility is spreading to stocks and corporate bonds.

“These moves are starting to cause worries across all asset classes,” James Wilson, a money manager at Jamieson Coote Bonds Pty in Melbourne, told Bloomberg. “There’s a buyer’s strike at the moment and no one wants to step in front of rising yields, despite getting to quite oversold levels.”

Why is it happening?

Markets are reckoning with higher-for-longer interest rates. Long-term yields on government bonds have been rising since mid-July, but accelerated after the United States Federal Reserve drove the higher-for-longer message home in September.

Even countries with more dovish central banks have had their bonds affected by the rise in Treasury yields. Swelling government deficits and increased bond supply are compounding concerns.

What about Canada?

Yields in Canada are rising as well. Earlier this week, the Government of Canada five-year bond yield jumped to a high of 4.46 per cent before retreating, Steve Huebl for Canadian Mortgage Trends said in an article. Over the past two weeks, yields have risen by more than 30 basis points.

Since bond yields lead fixed-rate mortgage pricing, these rates are also on the rise.

“Fixed-rate [mortgages] are flying,” mortgage analyst Rob McLister said in his MortgageLogic.news newsletter this week.

On Oct. 3, HSBC Bank Canada raised its leading uninsured five-year fixed to 6.14 per cent, which McLister said is Canada’s lowest nationally advertised bank rate. That puts the minimum qualifying rate above eight per cent for the first time since 1995.

McLister expects more lenders to raise their rates this week, and some could be by 20 basis points or more.

There are bigger risks

Considering the last breakout in yields resulted in the collapse of several U.S. banks, many are beginning to question whether the financial system can absorb such large losses this time, said Jocelyn Paquet of National Bank of Canada, who believes Europe is especially vulnerable.

The problem is that banks’ assets include government bonds. As the value of these assets declines, unrealized losses increase. This by itself may not lead to a banking crisis, but it is likely to force banks to pull back on their lending, which will slow the economy.

Governments will also feel the strain because bond yields determine their funding costs.

Bank of Montreal chief economist Douglas Porter said Canada’s extraordinary spending looked affordable when interest rates were near zero during the pandemic.

“With yields now rocketing to levels not seen since pre-GFC days, the calculus just changed rather abruptly,” he said. “Interest costs on government debt are rising rapidly.”

Canada’s public debt costs hit $3.85 billion in July, the highest in 27 years. And because government debt rolls over slowly, he said these interest costs are bound to rise.

When will it end?

Nobody has the answer to that, but there are theories.

Barclays PLC analysts said there is only one thing that will bring bond yields back to earth: a slump in stocks that makes fixed-income assets appealing again.

“There is no magic level of yields that, when reached, will automatically draw in enough buyers to spark a sustained bond rally,” analysts led by Ajay Rajadhyaksha said in a note. “In the short term, we can think of one scenario where bonds rally materially. If risk assets fall sharply in the coming weeks.”

Additional reporting by Bloomberg and Reuters

__________________________________________________

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

_____________________________________________________________________

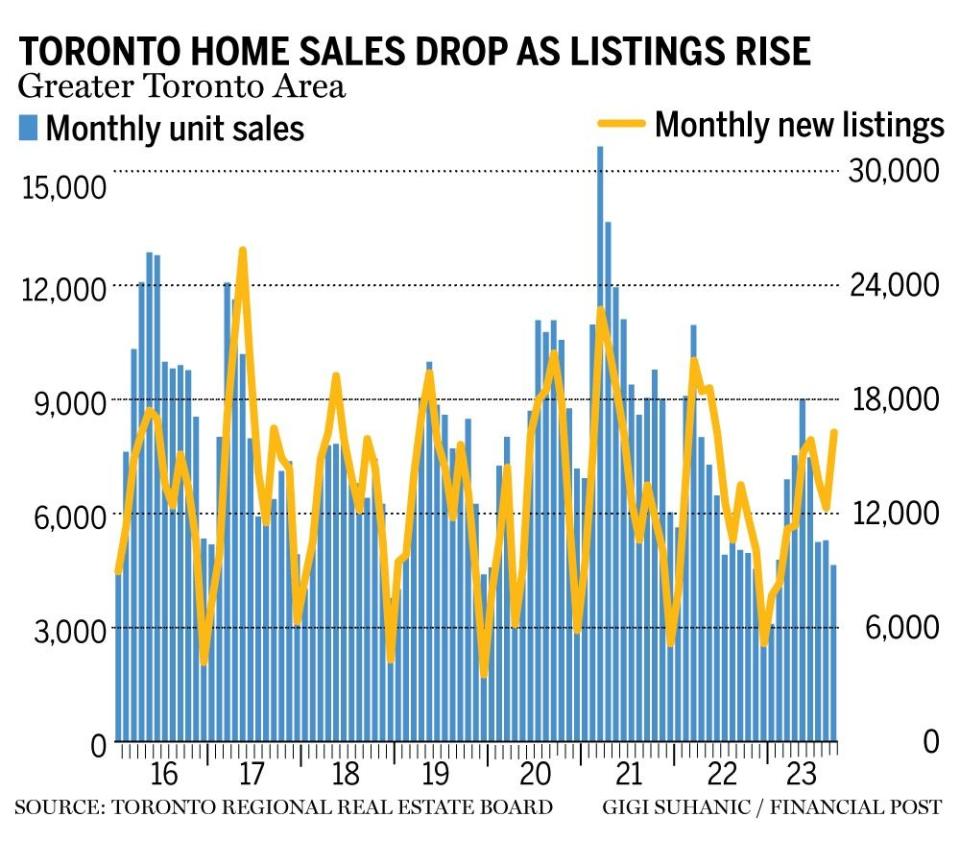

Canada’s biggest real estate market has fallen into buyers’ territory, the latest numbers reveal. Toronto home sales fell sharply in September, while new listings surged, pushing the sales to new listings ratio to 28.6 per cent. Anything below 40 on this ratio suggests a buyer’s market.

That might mean better deals for buyers to come, but prices in the GTA are still rising. The average price rose about three per cent in September to $1,119,428, from the month before.

Today’s Data: Canada trade numbers for August come out today and the trade deficit is expected to widen. Also on tap, U.S. goods & services trade balance and the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

Earnings: Constellation Brands, Conagra Brands

Get all today’s top breaking stories as they happen with the Financial Post’s live news blog, highlighting the business headlines you need to know at a glance.

_______________________________________________________

Defined-benefit pension plans may be poised for a comeback after a recent contract win by Canadian auto workers. David Sali looks at how higher interest rates and a shift in power toward employees are helping to fuel a DB renaissance. Read more

____________________________________________________

Today’s Posthaste was written by Pamela Heaven, @pamheaven, with additional reporting from The Canadian Press, Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg.

Have a story idea, pitch, embargoed report, or a suggestion for this newsletter? Email us at posthaste@postmedia.com, or hit reply to send us a note.

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.