When the Bucur family purchased their three-bedroom home in Romania 12 years ago, they took out a mortgage of around €80,000. Today, they owe the equivalent of over €140,000, despite having regularly made their monthly payments. That is because the original loan was denominated in Swiss Francs: the Swiss currency has strengthened by over 50% against the Euro since 2007, rising steeply during the Euro crisis in late 2008.

Eventually, the Bucur’s monthly payments also jumped massively, leaving them unable to keep up with payments. The two artists, along with their son and Ms. Bucur’s father who lives with them, are on the brink of losing their home.

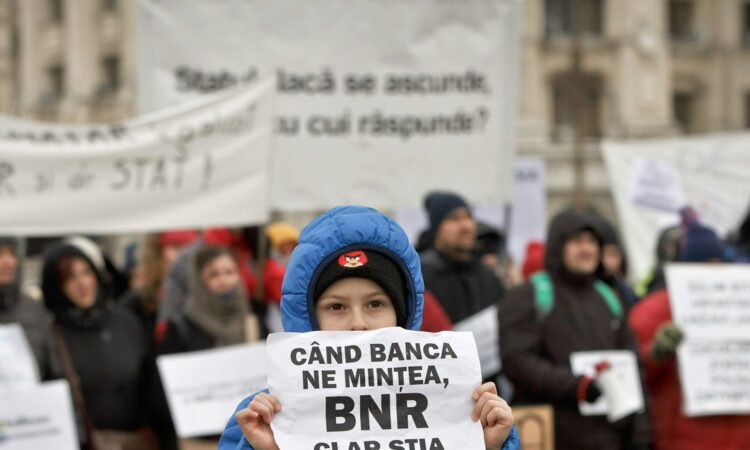

They are not alone. Tens of thousands of people not only in Romania, but across East and Central Europe, took out Swiss Franc denominated mortgages during the lending boom of the mid-2000s, attracted by low interest rates, only to be plunged into deep debt by the shift in currency exchange rates.

The Bucurs’ case stands out because of the approach their lawyer, Alexandra Burada, is taking in the Cornetu District Court with the support of Open Society Justice Initiative: raising human rights arguments in defense of the place they have called home for so many years. For the first time ever, a Romanian court is being asked to tackle the question whether repossession is a proportionate response, in light of the EU rights that apply when people fall into arrears repaying a home mortgage and face the loss of their home.

This argument may be new in Romania, but it has already been successfully made in Ireland, where the Open Society Justice Initiative and the Open Society Institute for Europe first engaged with local partners to introduce EU consumer and fundamental rights arguments into home possession cases, in the framework of the Abusive Lending Practices Project. As part of this cooperation, Open Society Justice Initiative’s Economic Justice Project has in recent years supported Irish lawyers and consumers’ in using the EU’s Unfair Contract Terms Directive and decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) interpreting the directive in these cases.

Specifically, we have been making the case that EU law requires that domestic courts review mortgage agreements on their own initiative to determine whether they contain any unfair terms, and delete those terms. We have also been arguing that EU law requires that domestic courts, when requested to do so by consumers, assess the impact of possession on the residents of the home, and, in particular, on their human rights under the European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights before entering a possession order.

Our interest in the intersection of consumer and human rights was spurred by a line of decisions in which the EU’s top court showed an increasing willingness to consider EU fundamental rights to protect consumers in mortgage enforcement procedures. In March 2013, the CJEU ruled in the Aziz case that evictions carried out in Spain violated EU consumer protection and human rights law because they did not allow national courts to stop evictions taking place due to possible unfair terms in mortgage agreements. The court concluded that Spain’s harsh possession laws did not comply with the right to an effective remedy and a fair trial, as guaranteed under the Charter (Article 47). The Aziz case was the first to demonstrate CJEU decisions are capable of addressing (at least part of) the abusive lending problem in Europe.

Then in 2014, in two further important decisions (Morcillo and Kusionova), the CJEU applied procedural protections from the Charter to protect consumers’ rights and stated that a fundamental right under the Charter—in that case, the right to accommodation (Article 7)—must be considered when member states implement EU law.

But these legal developments will not translate into meaningful change on the ground for consumers if European lawyers are not using EU law and CJEU case law in their arguments in domestic courts, or if judges across Europe do not apply them. That is why we have been arguing that the substantive protections in the Charter (which also include rights to dignity, respect for physical and mental integrity, private life, a high level of consumer protection as well as the rights of the child, the elderly and people with disabilities) must be considered when courts enforce any mortgage debt where borrowers face the loss of their home.

Our efforts have already yielded considerable success in Ireland. In March of this year, the Irish High Court in the Grant decision confirmed that EU law protects people at risk of losing their home. As a result, it is now clear that Irish courts are obliged to assess mortgage documents for unfair terms on their own initiative, even if borrowers do not specifically ask them to do so. They will then have to delete any terms they find unfair before entering a possession order, in accordance with the EU Unfair Terms Contract Directive. In addition, when asked to do so by borrowers, Irish courts must take Charter rights into account and consider the impact of the loss of the family home on the residents.

Will Romanian courts follow suit? The Bucurs certainly hope so.