Pon Sagnanert and Xiaoqing Zhou

The U.S. economy has been surprisingly buoyant since the Federal Reserve began tightening monetary policy in March 2022. In the almost two years since then, the effective federal funds rate has increased from nearly zero to almost 5.5 percent. Whether the economy’s resilience will continue in 2024 remains an open question.

One popular view is that historically high interest rates will eventually have their intended effects—damping demand and substantially slowing the economy—though this takes time because of long lags in the monetary policy transmission.

An often-cited example to explain the long lags is the extremely slow adjustment of the mortgage rates that existing borrowers pay. This is because most residential mortgages in the U.S. have 30-year fixed-rate terms, a unique feature of the U.S. housing finance market. However, after comparing economic data of the U.S. and other major advanced economies, we find tentative evidence that the slow adjustment of the outstanding mortgage rate in the U.S. has not played an important role in delaying the intended effects of the monetary tightening.

Outside of the U.S., variable-rate and short-term fixed-rate mortgages dominate most mortgage markets. This distinction means policy rate hikes should pass through to existing borrowers much faster abroad. As a result, we would expect these countries to experience weaker consumer spending, stronger deceleration in inflation and slower house price growth relative to the U.S., all else equal. These outcomes don’t appear to have occurred.

Mortgage market composition impacted monetary policy pass-through

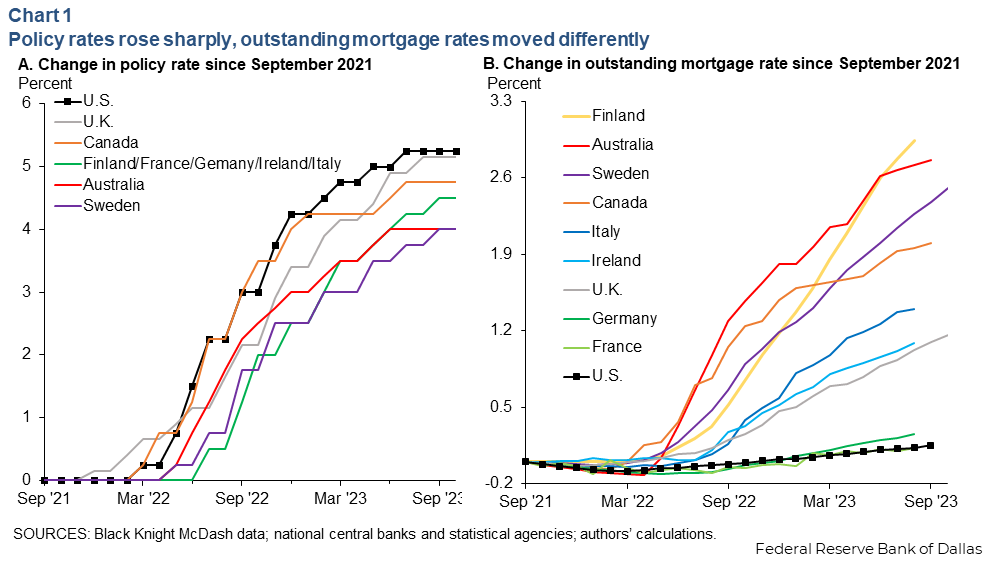

Major central banks seeking to fight surging inflation have raised their policy rates since early 2022. These actions, as well as expectations about further moves, swiftly pushed up long-term borrowing costs on new mortgages. However, changes to the mortgage rates paid by existing borrowers varied across countries (Chart 1).

In the U.S., the average rate on outstanding mortgages increased very slowly, by about 20 to 30 basis points (0.2 to 0.3 percentage points), from late 2021 to September 2023. This is in sharp contrast to a 400-basis-point increase in the rate on newly issued mortgages. France and Germany experienced similarly slow adjustments.

In contrast, the average outstanding rates in Australia and Finland, for example, rose almost 300 basis points, tracking closely the changes in their market rates on new mortgages. In other countries, such as the U.K. and Canada, a large portion of market rate increases was passed on to the average borrower.

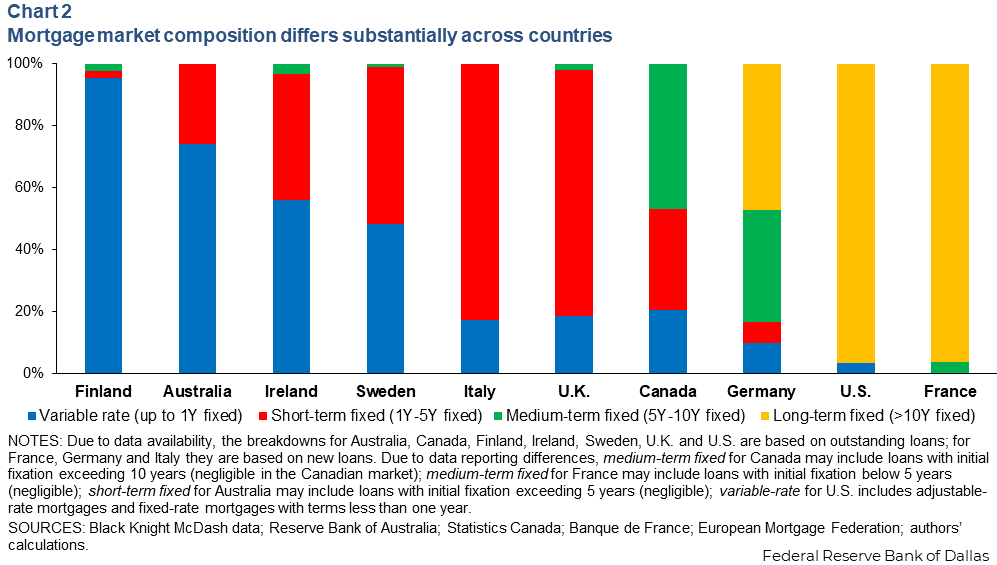

Mortgage product offerings could be behind the stark difference in the pace of policy rate pass-through. Using European Mortgage Federation standards, we categorized mortgage products into variable rate (with an initial fixed rate for up to a year), short-term fixed rate (rates fixed for one to five years), medium-term fixed rate (five to 10 years) and long-term fixed rate (more than 10 years). Chart 2 shows the breakdown of mortgage products by country in the fourth quarter 2021, just before the global tightening cycle.

Long-term fixed-rate mortgages tend to predominate in the U.S., France and Germany, while variable-rate and short-term fixed-rate mortgages are common in Australia, the U.K. and other European countries. The Canadian market, dominated by five-year, fixed-rate mortgages, falls somewhere in between.

The unusually large proportion of long-term, fixed-rate mortgages in the U.S. is partly a result of government-backed secondary market institutions—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, for example—that help lower the costs of these mortgages. Securitization through these institutions allows U.S. mortgages to be held and traded by investors worldwide. Outside the U.S., variable-rate and short-term fixed-rate mortgages are more common because banks (which dominate mortgage lending in these countries) hold loans on their balance sheets funded by deposits.

Retail sales appear less resilient where faster policy pass-through prevails

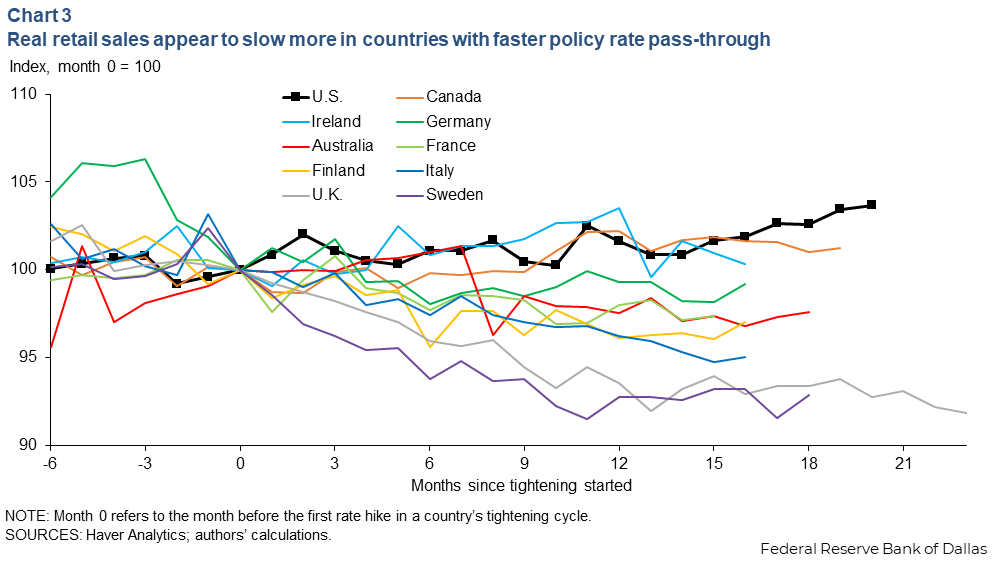

A larger increase in a country’s average outstanding mortgage rate implies higher mortgage payments for borrowers, all else equal. This lowers disposable income and leaves less room for discretionary spending. From a cross-country perspective, we expect countries with faster policy pass-through to have experienced weaker consumer spending and slower inflation relative to countries such as the U.S.

We start by examining real (inflation adjusted) retail sales, a monthly indicator of discretionary spending primarily on goods. Most countries in our sample have experienced gradual declines in retail sales since the beginning of their tightening cycles (Chart 3).

By comparison, U.S. retail sales stand out, increasing and remaining resilient. Likewise, Germany and France, countries with slow policy pass-through, experienced relatively smaller retail sales declines than other countries on average. This supports the view that slower pass-through of rate hikes to the average borrower may have contributed to resilient discretionary spending on goods.

Consumption growth, core inflation not slower in countries with greater policy pass-through

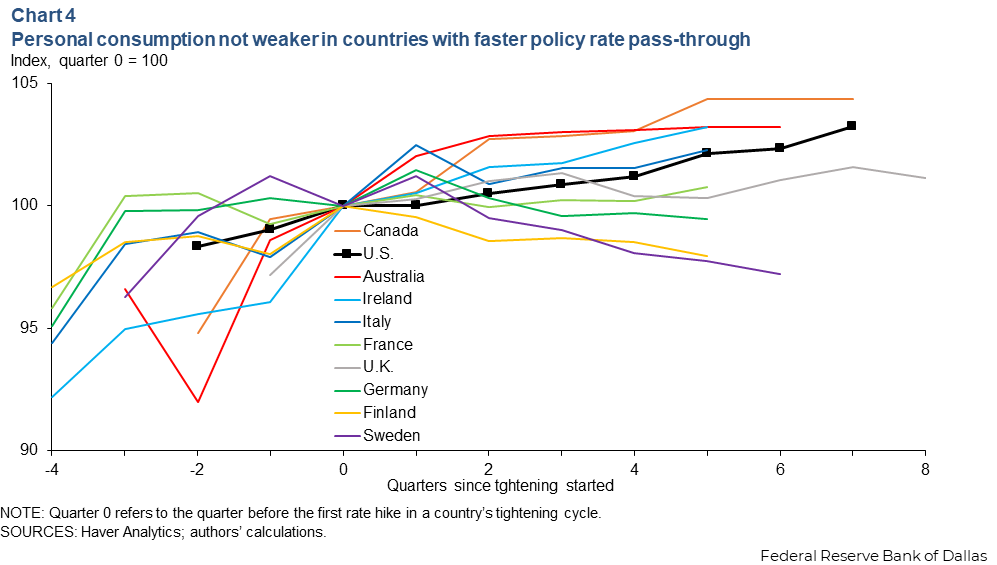

Retail sales, however, only reflect a small part of overall consumption in national accounting. They do not cover spending on various services. For a more complete picture, we turn to real quarterly personal consumption expenditures.

In this case, the resilience of U.S. consumption no longer stands out. Likewise, consumption in France and Germany has, if anything, grown more slowly than in other countries on average (Chart 4). This evidence suggests that overall consumption has not been weaker in countries with faster policy pass-through.

Two additional pieces of evidence support this conclusion. First, vehicle sales—a key measure of durable purchases often employed in academic studies to gauge the effect of mortgage rate changes—do not appear to be weaker in countries with faster policy pass-through. Second, regression analyses that control for country-specific effects and region-specific time trends yield the same pattern: Countries with faster policy pass-through have not displayed significantly lower growth in overall consumption or vehicle sales.

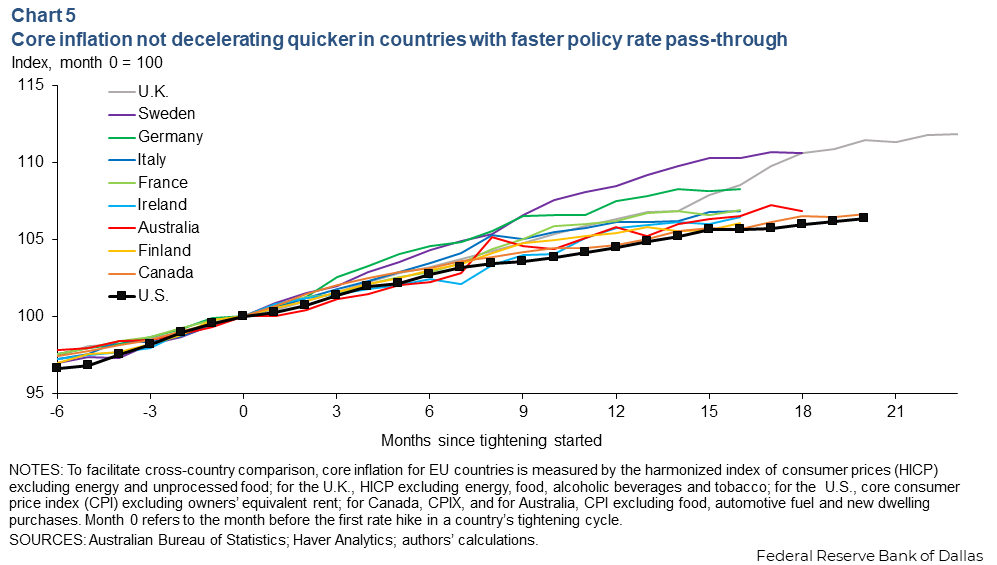

Turning to inflation, we focus on measures of core inflation, ones that abstract from the impact of energy price shocks and seek to control for the different treatment of owner-occupied housing in national consumer price indexes.

Chart 5 shows no support for the view that countries with faster policy pass-through have experienced greater inflation deceleration than countries such as the U.S. In fact, U.S. inflation has been at the lower end of the cross-country distribution since Fed tightening.

Overall, there is no significant difference in the inflation progress between countries with faster and slower policy pass-through. If anything, inflation in the latter group seems to decelerate faster.

House prices rebound after initial declines

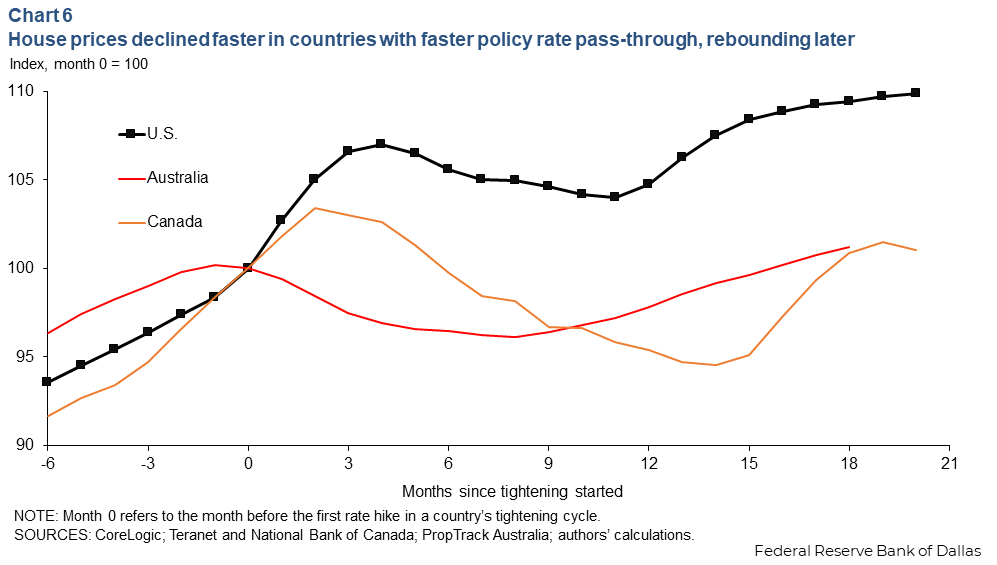

House prices provide another important indicator of the effect of monetary tightening through the mortgage-borrowing channel. While house prices are expected to soften in all countries in a rising rate environment, one would expect them to fall faster and by more in countries dominated by variable-rate or short-term fixed-rate mortgages. This is because expected increases in future policy rates would be more quickly translated into higher mortgage payments for homeowners, making ownership less attractive.

Due to large differences across countries in the construction of national house price indexes, we focus on three countries that have comparable, high-quality and repeat-sales-based indexes available monthly—the U.S., Canada and Australia. These three countries also represent varying degrees of policy pass-through.

Movements in these indexes within the first year of monetary tightening are broadly consistent with our expectations (Chart 6). Australia, where mortgages are mostly variable rate, experienced the fastest weakening of house prices, while declines came later for Canada and the U.S.

Surprisingly, however, house prices started to increase after their initial decline in all three countries. This rebound suggests that, even though the speed of policy pass-through may have affected house prices at the early stage of monetary tightening, this impact appears to subsequently subside.

Monetary policy impacts likely not delayed, but constrained

Most U.S. households had locked in ultra-low mortgage rates before the Fed raised interest rates in 2022—often cited as a prominent reason for seemingly long lags of monetary transmission. According to this view, the intended effects of tightening may have just been delayed.

Our tentative evidence does not support this view: Countries with faster pass-through of rate hikes to existing mortgage borrowers have not experienced weaker overall consumption or slower core inflation. Moreover, house prices have already rebounded in these countries after initially declining.

Our evidence suggests that the surprising resilience of U.S. consumers against the backdrop of monetary tightening may not reflect a delay in the monetary transmission. Rather, it may be due to a weakening of monetary transmission, based on the estimates of the effects of monetary policy (including on inflation and output), or the countervailing effects of other factors. For example, the surprisingly strong labor market may have undermined the intended effects of the tightening.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.