With Europe and the US scheduled to go live with Basel III implementation from 2025, Monsur Hussain, head of financial institutions research, and Christian Scarafia, head of northern European bank ratings, at Fitch Ratings, discuss the impact and implications of Basel III for banks under the new guidance

Banks’ internal models and their use in financial regulation have been among the most controversial topics in authorities’ discussions since the global financial crisis that began in 2007–08. The final Basel III reforms, which generally apply to large internationally active banks, mark a key turning point. They limit the influence of internal models on prudential capital by imposing a floor on the benefit from using internal models to 27.5% and fixing internal model risk weightings to prescriptive standardised weightings.

As Fitch Ratings is a credit rating agency, let’s start with a big-picture question: is the Basel regime positive or negative for creditors, and does it change ratings in any case?

Christian Scarafia

Christian Scarafia: All else being equal, more capital in a bank is positive for creditors as it increases the buffer to absorb losses before creditors take a hit.

However, what remains unclear is how banks will change their business mix, and what – if any – unintended consequences the new rules will have. This means it is too early to say if and how bank ratings might be affected – particularly if we take into consideration the transition period, which can be very lengthy.

Banks have always adapted their businesses whenever the rules are changed, and we have seen this in the past – if we remember the impact of Basel II, banks had to implement the rules, build up significant capital and ensure their businesses continued to make adequate returns.

Another point worth highlighting at the outset is that risk sensitivity was one of the reasons internal ratings were introduced into capital requirements with Basel II in the first place. The purely standardised approach (SA) under Basel I meant banks had an incentive to increase risk exposure, as transactions that require less regulatory capital than economic capital under a purely standardised model are more remunerative for a bank.

I believe it is fair to say – from a big-picture perspective – that banks will meet the tougher requirements, but the full consequences on each bank’s business mix and therefore risk profile are not yet clear.

Breaking down where the impact lies, how do Europe, the US and Asia-Pacific (Apac) compare?

.jpg)

Monsur Hussain

Monsur Hussain: For years, regulators’ quantitative impact studies have consistently provided guidance that larger European banks in particular would face the highest increase in minimum requirements of around 15% in Tier 1 capital, which is far more than banks based in the Americas – predominantly North America – which are facing an increase of around 5% in similar minimum requirements. By contrast, banks in the rest of the world – predominantly Apac – could even see minimum requirements fall under the final regime.

Implementing the global standard into legally binding local requirements has also led to differentiation in impact. For instance, the European Union has recently reached a political agreement to implement the final Basel III regime, and it has watered down the impact of that output floor by reducing capital needs for unrated investment-grade corporates and lower loan-to-value (LTV) residential mortgages in particular. The result of that is to halve the expected impact to between a 6–8 percentage point increase in minimum Tier 1 capital requirements.

In contrast, the US has gone in the other direction with recent draft proposals by eliminating the use of credit models for prudential requirements and gold-plating its requirements for residential mortgages, relative to the global standard. In addition, operational risk and market risk requirements weigh quite heavily on the largest US banks, relative to their European peers, meaning the increase – in particular for the largest US banks – will be more akin to that for European banks.

Did that move come as a surprise? What are the structural and other features of the European banks that are leading to this outcome?

Christian Scarafia: US banks don’t hold large volumes of low-risk mortgage loans on their balance sheets, and for a long time they have had the Collins Amendment backstop – meaning capital ratios calculated under the SA are the binding constraint whenever they are tighter than those resulting from internal models. This – alongside leverage ratio requirements that have been in place in the US much longer than in Europe – incentivises banks to hold higher risk-weighted exposures.

Output floor restrictions most impact banks that make extensive use of internal models for capital calculations with relatively low-risk assets on their balance sheets – and northern European banking groups fit that profile particularly well, given the long history of very low loan losses or credit losses – particularly on housing loans.

However, these banks generally operate with high capital ratios, well in excess of regulatory minimums. So the increase in risk-weighted assets (RWA) can be accommodated and, as previously mentioned, the glide point of when the fully loaded requirements will bite is quite lengthy.

Focusing on Europe, are there any regional disparities between banks?

Christian Scarafia: Within Europe, the big picture is that southern European banks make less use of internal ratings-based (IRB) models than their northern European peers, and their loan portfolios have historically been riskier because of economic performance at the time. Modelled IRB risk weights have been higher there, so there is less of an issue when the output floor hits than for some northern European banks.

Turning our attention to credit products, are particular products offered by banks impacted more than others because of the output floor interacting with the IRB and standardised weightings?

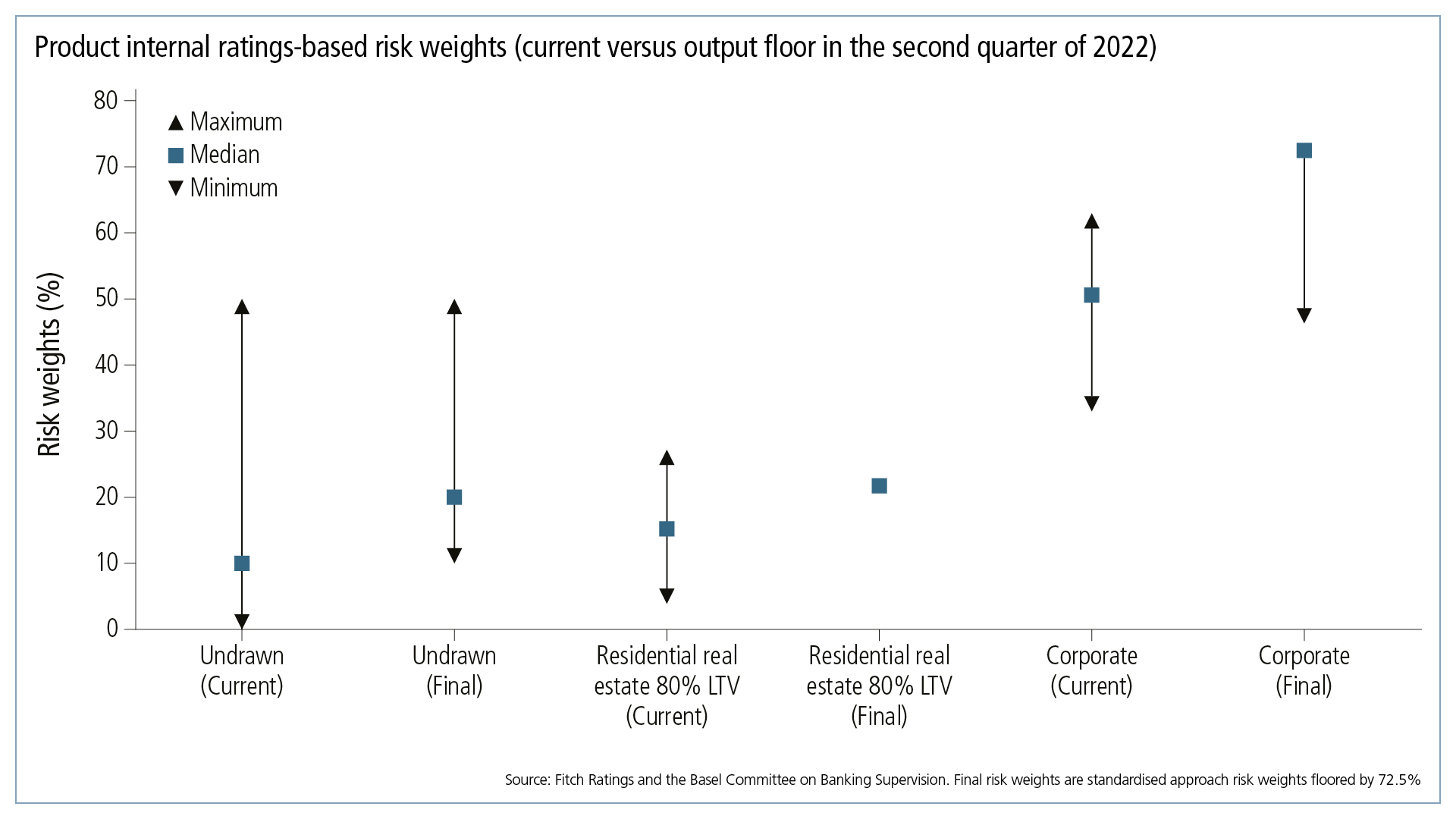

Monsur Hussain: Absolutely. The key point here is comparing and contrasting the prevailing capital requirements via the models on the one hand versus the increase that occurred to these products because of the application of standardised weightings due to the output floor on the other.

So we’ve run a rule across different products and found that non-traded equity positions see a big increase under the new regime – as do corporate loans and facilities.

However, the type of corporate counterparty here is really the key. Unrated corporates are potentially experiencing quite a big jump in terms of capital requirements versus rated corporates – in particular credit ratings above investment grade, where they see a much smaller capital increase, if at all, under the new regime.

Mortgage loans – in particular low-risk, low-LTV mortgages – currently, under modelled approaches, attract very low capital requirements. These will also see an increase, in some cases more than double. Project and infrastructure finance loans also face a steep increase in capital requirements – including transactions that are unrated as an intended consequence of deliberately removing some low-risk weights generated by internal credit models.

Is that fair on banks?

Monsur Hussain: The valuation of banks’ equity positions can be volatile, so increasing weightings above those given for corporate senior debt exposure does make sense in the new regime, and the standardised weightings under the revised framework pretty much line up with the IRB weightings in some respects under the output floor.

However, that could impact, for instance, Japanese banking groups with their extensive cross shareholdings and other banks that have significant equity exposures.

Otherwise, for most commercial banks, changes to corporate exposure classes can lead to large shifts in capital requirements, considering the materiality of corporate exposures or facilities generally on banks’ balance sheets. As previously mentioned, this is particularly the case if the counterparty is unrated. To that point, facilities might see a big increase in capital requirements because, ultimately, the conversion of those undrawn facilities to a drawn equivalent under the SA carries a minimum floor that does not exist if you’re using internal models to estimate the potential of that facility to be drawn.

Going forward, the behaviour of customers becomes much more important under the new regime as clients who fully repay their outstandings at the end of each month, as transactors, will require far less capital to be held against those facilities than if the outstandings remain, so banks might start differentiating charges based on behaviours more stringently.

It is worth stressing Christian’s point that, for residential mortgages – particularly in northern Europe – small percentage point risk-weight increases can still amount to a material increase in capital requirements. In some cases more than doubling, which can then matter for banks with large mortgage portfolios or those that have a mono-line business.

Since the output floor increases capital requirements even for low credit risk products, will banks be incentivised to dial up their risk appetite?

Christian Scarafia: That could certainly be the case. An example might be when leverage requirements were introduced for European banks some years ago. Then, some European banks that had concentrated on very low-risk and low-margin businesses saw that the leverage ratio was becoming a binding constraint, which meant they had to optimise between the leverage ratio and the risk-weighted ratio, resulting in the RWA density of some balance sheets increasing, indicating that risk exposure had increased.

Something similar could happen this time around, as banks will now have to redo their calculations and optimise for the output floor.

Monsur Hussain: You could also take the example of what we saw in the US, where there has long been a structural balance sheet tilt towards higher risk density products, as there is a great deal more credit intermediation via the capital markets than via the banks. There’s also a more conservative risk-weighting regime in the US, generally, because of the permanent output floor in place under the Collins Amendment, which has incentivised US banks to hold or originate generally more risky or risk-weight-dense products. The US agencies also play a key role in shaping banks’ balance sheets by taking those low-risk mortgage products off of the US banks’ balance sheets and putting them through to the capital markets, and the US banks end up holding the agencies’ debt.

The latest proposals might convince banks to dial up their risk appetite or divest themselves of portfolios where the economic capital for a given product is much lower than the regulator-defined capital requirement.

Otherwise, the pricing of products might be impacted, although Fitch Ratings would argue the cost of capital is just one aspect, alongside the cost of funding and competition, including that from the non-bank sector.

To what degree will non-banks be tempted to intermediate on credit to the extent some bank executives have indicated recently in the US, and over the past few years in Europe?

Christian Scarafia: This has been an ongoing trend for some time. In the US, more than half of residential mortgage originations are from the non-bank sector and via capital markets intermediation. The rise of private credit has already accelerated, bringing in credit funds and the insurance sector.

Tougher bank regulations will force banks to look at their business models, and this means some products could go to the non-bank sector – and that includes life insurers that might find longer-duration assets attractive given their long-duration liabilities.

Monsur Hussain: To add to Christian’s point: some of this is intended from the regulators, and we’ve seen regulatory authorities in the insurance sector tweaking the rules to make it easier for insurers to do some heavy lifting to substitute for the banks. This is particularly true on long-duration assets where there’s good matching between insurance risk profiles and their desire for long-duration cash flows and returns.

However, there are potential implications here from a financial stability perspective if significant credit intermediation activity arises from the less well-regulated spheres. That might then lead authorities to intervene if non-bank lenders become systemic, for instance, or to prevent disorderly contagion risks. Ultimately, we believe that growth from the non-bank sector will lead to pressure for greater regulation of intermediaries that are currently less regulated. So watch this space.

For more insights on this topic, visit Fitch Ratings’ website