A question. How much money have me and my fiancée spent paying rent? Answer: just under £100,000. That is £1,389 a month and around £46 a day over our six years renting.

And have we come out of this experience as owners of a one bedroom flat somewhere – anywhere- within an hour’s commute of our work? No, don’t be silly.

I’m 29 – the age at which my parents were already onto the second home they owned – my dad paid just £25,000 for a brand new flat in Eastbourne while my mum had a two-bed, semi-detached house for £34,000. I had hoped a price crash would help me buy, but oh no.

Just as prices start to fall, mortgage rates have rocketed – with landlords passing on their increased costs to tenants – and, just for good measure, Help to Buy has just been axed.

There are a lot more of us who rent now than when my parents were young.

Nearly one in five UK homes are now rented, and across England, rents have risen by 30 per cent in five years – up from £1,056 to £1,354.

Despite soaring rents, demand is through the roof, meaning market values are up – and rent is extortionate.

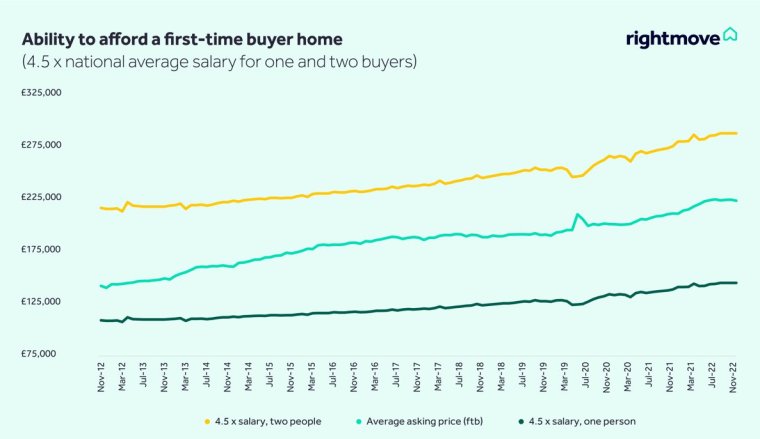

There are a whole host of reasons young people can’t own their own property but, of course, the main one is affordability.

A potted history of our renting story. My partner, Adam, and I’s first home – I use the word loosely as you can’t make any adjustments without a hefty chunk being deducted from your deposit – was a one bedroom in Canterbury.

We lived there for two happy years six years ago, paying £775 a month between us, with my partner footing more of the bill after I went back to university to study.

We then moved to the Big Smoke, renting out a tiny one bedroom flat on a housing estate in Tooting for a £1,350 a month.

Everything you can think of going wrong in a property went disastrously wrong.

The fridge-freezer broke, the dishwasher wouldn’t work, the wires above the electric shower sparked when you were washing, and the bathroom fan wouldn’t turn off when you turned the light switch off, leaving a constant humming noise rattling in your brain.

Every time I called the landlord, he would say: “You can’t call me with every problem, Grace. Why don’t you sort some yourself?”

We couldn’t wait to leave that flat but when our break clause of 18 months finally came up, we didn’t go far. In fact, we moved on to the same estate, just a 60-second walk up the road, to a wonderful two-bed, this time costing £1,550.

More on Home Ownership

This flat could not be more different to the one before – it was light, airy and homely. The neighbours were great and all of the household appliances – shock, horror – worked.

Then, with very little warning, we were turfed out after nearly two-and-a-half-years. It was a stark reminder we were occupants in someone else’s home – this was not our own space.

To be fair, the landlord had kindly agreed to move in a family of Ukrainian refugees, who, of course, were much more deserving of the space than us. That is not in question.

But it did leave us, in July, with a month or so to find a new property. The market was crazy – though not as crazy as it is now – with a lack of supply pushing up prices exponentially.

We landed on a two bedroom, terraced house, again in Tooting Bec – this time five minutes away from the estate.

However, we are now paying £1,800 a month. For other Londoners, this is unlikely to be shocking but for people from other parts of the country, this seems like a staggering amount.

Our renting journey continues but I think anyone can agree the sum of £91,950 would be a handsome deposit. Even in London, this would go a long way towards a mortgage but instead the money has been used to line landlords’ pockets.

This doesn’t even cover the three years renting at university – although some of that was covered by grants.

The amount made me feel a bit sick when I added it all up, I won’t lie, and my fiancée’s expletive laden response to the figures cannot be published in a family newspaper.

But what can we do? We’re already in a fortunate position to be in two, full-time, well-paid jobs. But even so, with rent, bills and other regular outgoings, there’s little left over to save.

And even with what we can scrape together, it will take years to amount to anything close to the tens of thousands needed for a deposit in the current market.

There needs to be radical change to help younger generations on the property ladder – at the very least, the amount people have paid in rent for years should be taken into consideration when approving a mortgage loan.

As it stands, lenders are bound by FCA rules which mean mortgage applicants have to prove they can still afford to keep up their mortgage repayments if interest rates are to rise, which is even more likely as of now in an inflationary period.

But this doesn’t include taking into account a person’s ability to pay their rent on time, every time, as proof they can afford to meet an equivalent mortgage repayment.

It would also be good to bring back a similar scheme to Help to Buy, that enables people to get on the housing ladder with government funds they can pay back at a later date.

More from Property and Mortgages

Labour recently said it would introduce a “consumer rights revolution” for renters, if in power, which includes giving renters security by making three-year tenancies the norm and control on rent rises so that rents do not rise by more than inflation.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives have, on numerous occasions, pledged to help “generation rent”, by reviewing the system and allowing rent payments to be used as part of the affordability assessment for a mortgage.

However, after 12 years in power and not much to show for it, I think it’s safe to assume their heart isn’t much in it.

Generation Rent suggests changing the rules for landlords. Right now, they face much less strict affordability tests, and can also borrow mortgages they only need to pay the interest on. It means they can borrow more and often outbid first-time buyers, which ultimately pushes up house prices.

Other suggested alternatives include building housing that cannot be snapped up by Buy to Let landlords and is instead meant for first-time buyers only.

All – or indeed any – of these ideas would help first-time buyers immeasurably, but years have passed and young renters still find themselves in a similar situation.

Now, I am left to wonder how many more tens of thousands I will spend on rent in my lifetime – and how many houses I could have bought if the system was fair.