The interest rates currently being seen across Western countries will likely be the norm for many years to come, argues Kensington Mortgages capital markets director Alex Maddox

Due to the high inflation levels experienced in the UK throughout 2022, reaching a peak of 11.1% in the 12 months to October 2022, the Bank of England (BoE) had to significantly increase its benchmark interest rate, the Bank of England Base Rate (BBR), to curb inflation. There have been ten consecutive rises to the BBR, taking it from 0.1% in December 2021 to 4% as of February 2023, the highest rate in 14 years.

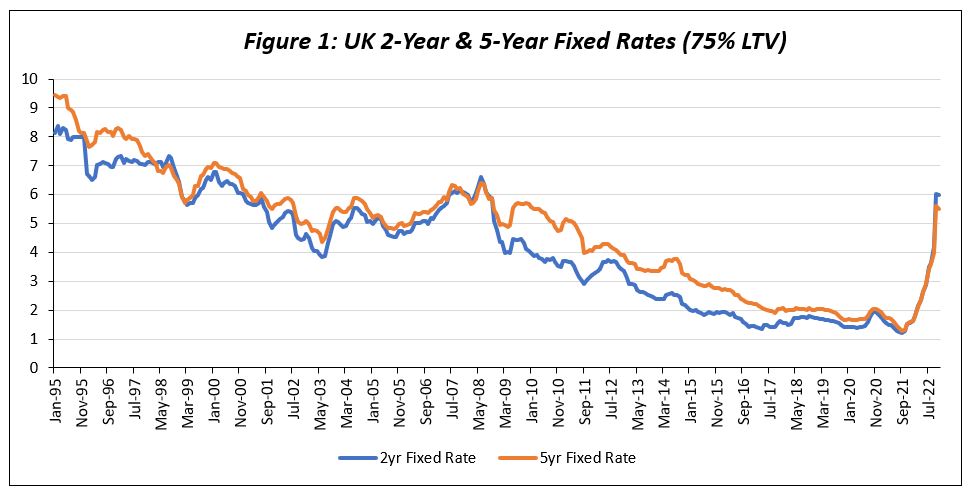

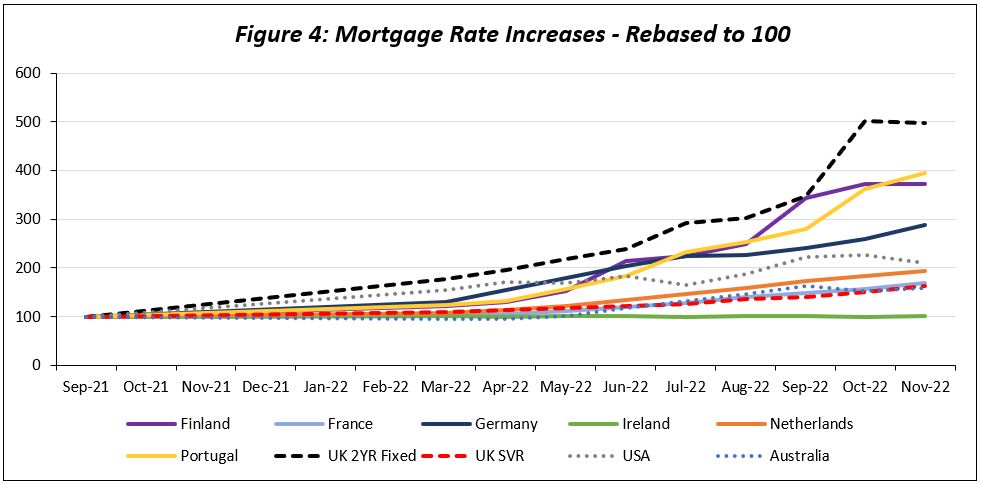

As a result of where markets forecast the BBR in the coming years, swap rates sharply increased throughout 2022 and have naturally been followed by mortgage rates, taking them from historic lows to levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Although current mortgage rates have not reached the highs seen in the mid-90s, the speed at which they increased in the last year will impact millions of UK customers seeking to refinance their fixed rate mortgage in the coming years, with rates up to five times higher within only 14 months.

The current picture

According to recent data, the Bank of England advised that around 2 million mortgages reached the end of their fixed term between Q4 2022 and the end of 2023 and that approximately 80% of them currently have a fixed rate below 2.5% (that is about 25% of the outstanding owner occupied (OO) and buy-to-let (BTL) mortgages expected to be refinanced in the next 12 months). Of those due to refinance in the coming year, the average balance is £130,000 with an average remaining term of 20 years and an interest rate of 2.0%.

Based on these figures, the average UK mortgage borrower is expected to pay £280 more in interest per month if they decide to refinance with another fixed rate mortgage. This is a surplus of more than £3,000 a year in mortgage bills versus what they currently pay, a painful prospect given the ongoing cost-of-living crisis.

Source: BoE Data (Latest data available to Nov-22)

In figure 1, the dramatic increase in mortgage rates at the back end of last year is evident. This was a result of the large jump in swap rates, which reflect the market’s expectations of where the BBR will be in the future. For example, the two-year swap rate is currently trading at around 4.1% which is the level at which markets expect the BBR to be in 24 months. Mortgage lenders use the swap rate levels to price their fixed rate mortgage products. The pricing of a two-year fixed rate mortgage, for instance, is calculated using the two-year swap rate plus a product margin which varies subject to the customer’s circumstances, property, and LTV.

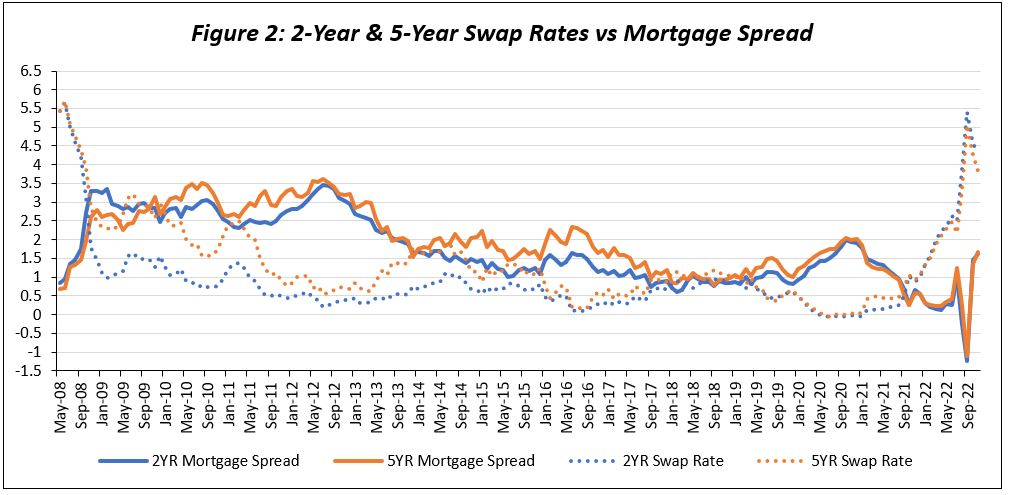

As can be seen in figure 2, the sharp and sudden increase in swap rates was detrimental to mortgage lenders as they were unable to immediately reprice their mortgage products, meaning that while swap rates were at highs, they continued to offer their current range of mortgage products at a loss or a much-reduced margin.

Source: BoE & Bloomberg Data

While we have seen some stabilisation in the swap markets since Rishi Sunak was appointed as prime minister, and a reduction in levels on the back of positive inflation news, rates remain at very high levels. In addition, although inflation is declining, it is still well above the BoE’s 2% target, meaning we expect swap rates to remain heightened in the near term on the back of further rate hikes expected from the BoE.

The outlook for the market, however, it is not entirely bleak. UK GDP has performed better than expected, growing 0.1% in November (it was expected to decline by 0.2%), meaning the UK is unlikely to be in recession just yet. Unemployment also remained at consistently low levels throughout 2022, the lowest they have been since 1974, and the UK inflation rate has fallen for two consecutive months, taking it to 10.5% in the 12 months to December.

Although inflation is still well outside of the 2% target, the BoE has advised that the terminal rate for the BBR is likely to be circa 4.5% in mid-2023 with smaller rate rises expected to meet the target. While mortgage rates remain higher than before, we have seen a slight recovery from the sharp rises at the end of last year. The latest data from November shows the two-year fixed rate at 5.97% and the 5-year at 5.49%, and we expect them to stabilise around these levels.

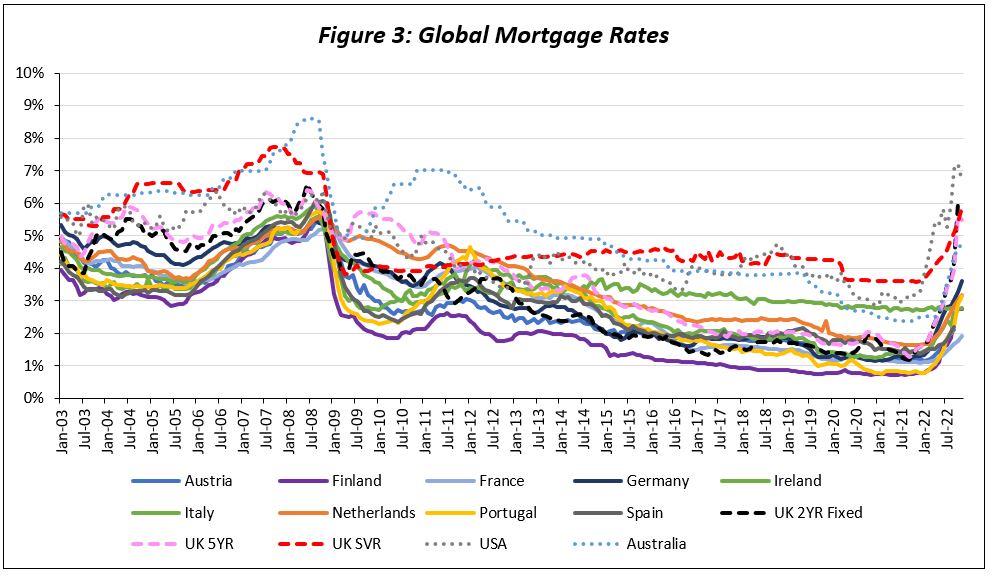

Sharp mortgage rate rises have not been confined to the UK, with increases in mortgage rates also seen across many other geographies around the world.

Europe

Similar to the BoE, the European Central Bank (ECB) increased rates to combat inflation throughout 2022, reaching a peak of 10.6% in the Eurozone in the 12 months to October. The ECB’s key interest rate was raised by 50 basis points in July 2022, the first increase in 11 years and the largest since 2000, and was increased by further 50 basis points in December. The rate is currently set at 2.5%, the highest level since 2008. This in turn has caused mortgage rates across the EU to increase, albeit more moderately than in the UK. Average mortgage rates across the Eurozone were at around 2.9% in November, their highest in seven years and 1% higher than at the start of 2022. With continued rate rises expected by the ECB in 2023, further increases are sure to materialise in the near term.

However, mortgage borrowers in certain geographies have not been impacted as much as the UK by the recent global rise of rates due to different mortgage funding models. In a number of countries such as the US or France, the dominant instrument in the market is long-term fixed rate mortgages (over 30 years). This contrasts with borrowers in the UK and Ireland, where it has long been common to fix for shorter periods of time such as two and five years, although fixing your rate for longer has become a more popular trend recently. Australian borrowers generally choose variable rate products and will likely be most impacted by sharp rate rises in the near term.

US

Last year, high inflation was widespread across the world, reaching a peak of 9.1% in the US in the 12 months to June. The US inflation rate has decreased in recent months and is currently at 6.5% in the 12 months to December. The US Federal Reserve, however, is maintaining its pledge to continue fighting persisting inflation with aggressive rate hikes, increasing rates to a new target of 4.5% to 4.75% in February and with more hikes expected even with falling inflation.

US mortgage rates recently rose above 7% for the first time in 20 years and mortgage applications in the US have been declining, reaching their lowest level since 1997. While those with an existing mortgage are likely to be less impacted due to the longer fixed terms taken, this will impact those looking to enter the housing market and will see first-time buyers pushed out as affordability is severely impacted. Similarly in France, although rates are much lower (currently around 1.91% for 30 years), many banks do not have an appetite to provide mortgages in the current economic backdrop. There are also no specialist lenders in France and only a limited number of banks that offer mortgages, preventing first-time buyers from entering the property market.

Australia

In Australia, the CPI inflation rate reached 7.8% in the 12 months to December, a 32-year high. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) recently raised rates by 25 basis points to 3.35%, a 10-year peak and its ninth consecutive hike, with 325 basis points of rate hikes since March last year.

Like the UK, with the combination of persisting high inflation, RBA rate rises, and a choppy economic backdrop, Australian mortgage rates have increased significantly throughout 2022. Although rates in Australia have been historically higher than the UK, they reached record lows post-Covid and have risen sharply in 2022, with an average three-year fixed term rate currently around 6% and average variable rate at 4.8%. In Australia, most borrowers opt for a variable-rate mortgage, although a much higher proportion during Covid preferred fixed deals due to the exceptionally low rates offered. Last year saw a reversion back to variable rate loans, with many Australians not wanting to lock in at the higher rates. This could put pressure on the budgets of many households, as rates are expected to continue rising to combat inflation and remain elevated for the foreseeable future.

Source: ECB, BOE, RBA & Bloomberg

Nb. The above shows average rates on loans to households each month for house purchases from monetary financial institutions in the respective countries

In figure 3, the US mortgage rate is the highest of those compared (as of the most recent update in November 2022), however looking at figure 4, the rate at which the UK two-year fixed rate mortgage has increased far outstrips it and is also the most increased rate across Europe. Due to the sharp increases, the UK standard variable rate, which is usually 2 to 3% above the two-year fixed rate, fell below the latter in October and November and is seen to be converging in December. Aside from Ireland, it was also the least increased rate across Europe last year.

Source: ECB, BOE, RBA & Bloomberg

Nb.: Total calculated by weighting the volumes with a moving average defined for cost of borrowing purposes and rebased to 100

What’s next?

Across the UK mortgage market, we have seen a reduction in the pipeline for new lending, and the most recent data from the BoE shows new mortgage approvals were down circa 40% between August and November 2022, with borrowers likely holding off on new house purchases in the current environment. We expect a drop in lending on new house purchases as borrowers are currently taking a double hit on their affordability due to increased living expenses and increased mortgage payments.

There are still many people who will be coming off of their fixed term this coming year and borrowers may not want to remortgage onto another fixed rate at current market levels. We therefore anticipate that we may see a temporary shift towards more tracker or floating rate products.

Although mortgage rates in the UK have increased significantly this year, we do not expect to see them returning to the low levels that we have become accustomed to over the last six years. Ultimately, the rates we are seeing now are likely to be our new norm for many years to come.