Analysis: property prices in Ireland and across Europe are falling for the first time in around a decade

We’ve become used to sky-high property prices. In fact, they recently surpassed Celtic Tiger record highs. But in recent months something different has been happening: house prices are falling across Europe. This is true in Ireland, too, where the housing market has appeared insulated against any change in the weather for quite some time.

But are we now looking at a bubble bursting — and a further fall in prices — or just a bit of a cooling off period? “I think there’s a couple of different dynamics at play in the housing market at present,” says Kieran McQuinn, Research Professor with the ESRI and adjunct professor of economics at TCD.

First, we need to talk about the pandemic because it had “quite an impact” on the housing market in Ireland, McQuinn notes. Then, people weren’t spending their money and going out because of the public health measures. “So demand was fuelled in that sense: people had extra savings that they could use to purchase housing. There’s survey evidence to suggest that’s exactly what happened.”

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s Drivetime, indications that house prices are falling for the first time in a decade

On the supply side, health measures initially hit the construction sector and then inflation caused the cost of building materials to go up, causing the supply of housing to fall back at the same time as demand was increasing. “That led to this huge surge in prices that we witnessed, particularly last year, but even before that in 2021 as well,” he says. By January 2022, prices were 15% higher in Ireland than the previous year and they finally began falling in January 2023.

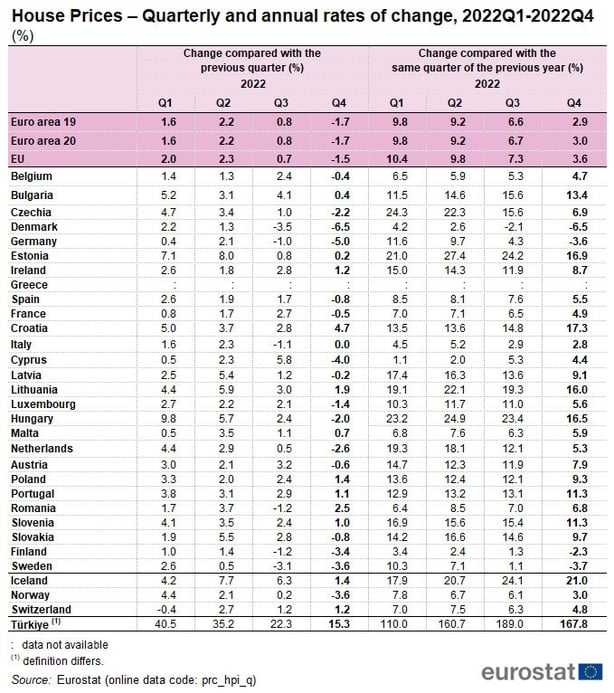

But although prices are technically falling across Europe, they’re falling from great heights. Public broadcaster LSM reports the Latvian housing market saw a 10% rise in prices between 2021 and 2022, while Slovenian prices also reached record highs in 2022, according to national broadcaster RTV. Finnish prices are also down on last year and demand is at a seven-year low, reports broadcaster YLE. Lithuanian property prices saw a whopping 22% increase at their peak in 2022 and unlike in most other European countries, price increases have slowed but not actually decreased, for now, reports Lithuanian National Radio and Television, LRT.

Sweden has seen its property prices plunge by around 15% and faces a recession. Česká televize, public television broadcaster in the Czech Republic, reports the demand for rental properties is up in the face of high interest rates and increased mortgage prices, which is increasing average rents. Similarly, German public broadcaster BR reports a trend reversal towards increased renting, as fewer and fewer people can afford real estate due to rising financing costs.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ News, national house price growth slowing in Ireland

Prices “simply can’t keep increasing at the pace at which they did last year because people can’t afford it. It’s as simple as that,” says McQuinn. So what we’re seeing is the market ‘cooling quite a bit’ in response. But this correction is being ‘aided and abetted’ by rising interest rates. “The rising interest rates really affect demand, it really hits affordability very quickly indeed.”

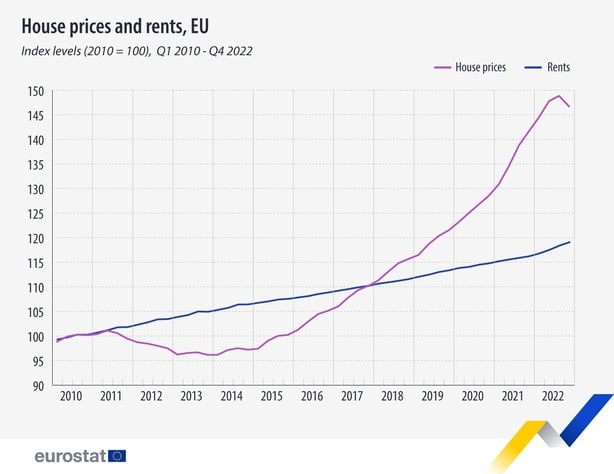

On the topic of interest rates, they seem to have played a part in reversing a very long trend. House prices in Europe had been steadily on the rise since the last bubble burst. Eurostat data shows prices have increased by 47% overall since 2010. Of the 24 EU countries whose data Eurostat recorded, prices increased in 24 countries and decreased in just three. House prices more than doubled in Estonia (+199%), Hungary (+174%), Lithuania (+142%), Luxembourg (+136%), Latvia (+133%), Austria (+126%) and Czechia (+125%). Meanwhile decreases were observed in Greece (-14%), Italy (-9%) and Cyprus (-4%).

But for the first time in a decade the European Central Bank (ECB) raised its interest rates in July 2022 as a response to a steep rise in inflation, against a backdrop of war in Ukraine and a cost-of-living crisis. Before this, interest rates had been on a downward trend for the best part of 15 years. The ECB’s sixth hike came in March of this year, pushing the rate up to 3,5%. It’s likely that we could see at least one more hike before the year is out.

Higher interest rates makes borrowing money, and therefore mortgages, more expensive. Eurostat figures show that by the end of 2022, house prices began declining in most EU countries. Based on cross-country evidence, the International Monetary Fund says a rule of thumb is, every one percentage point increase in real interest rates slows the pace of house price growth by about two percentage points.

“Crash” is too strong an expression to use about the current situation, says Andrea Lippi, Associate Professor of Economics at Cattolica University in Milan. “I would identify a possible real estate re-pricing in Europe,” he says, adding it’s difficult to generalise across unique, geographical differences. He highlights the vulnerability of variable mortgages to changes in interest rates.

Big interest rate increases contributed to the plunge in house prices in Sweden, where those particularly vulnerable variable (floating) and short-term mortgages are popular and interest rates have been very low, Sveriges Radio reports. In general, the Irish market has tended to vary over the years in terms of whether most people have had variable or fixed rate mortgages, and sometimes it’s been a 50/50 split, says McQuinn.

Of course, you can no longer get the infamous tracker mortgages, though many are still on them. Those on fixed rate mortgages are protected from rate changes for the duration of the fixed term, but once the contract is up, it’s a different story. A new report by Central Bank economists has found a fifth of Irish borrowers may face a hike of up to 50% in mortgage costs.

But the banking system, especially in relation to the mortgages granted in recent years, is much less exposed today compared to the crash in 2008, says Dr Enrico Cestari, Scientific Director of Executive Master in Real Estate, Luiss Business School. “Public authorities and central banks are doing their best to keep “panic” out of the equation,” he says.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s Today with Claire Byrne, Irish Independent’s Charlie Weston and Mortgage Switching Expert Martina Hennessy on the impact of rising interest rates on mortgage holders

Although interest rates are now high compared to the “all-time lows” we’ve had in recent years, they’re still below the “danger level” of the highs between 2013 to 2018, adds Cestari. “However, there is no doubt that this increase poses a period of uncertainty,” he says. The high levels of inflation erodes household savings and this reduces the possibility of getting access to bank credit for many. “Therefore, the combination of high interest rates and a high level of inflation can actually generate a slight contraction in some European zones.”

Cestari says the countries most immune to the current combination of high inflation and high interest rates, are those that have already started the process of expanding or renewing their real estate stock. In other words, those that are working on the issue of supply.

When it comes to supply, “it’s no secret that we haven’t really been building enough houses in the Irish economy over the past ten years,” says McQuinn. In Ireland, we had a “huge collapse” in supply levels that persisted up until about four years ago, he says. When the pandemic hit, this set the stage for soaring prices against a backdrop of persistent imbalance between supply and demand. The lag in supply of new housing has been a factor in price rises across many countries, including in France, where professionals in the housing sector have estimated a need to build 500,000 new homes a year, Franceinfo reports.

We need your consent to load this comcast-player contentWe use comcast-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Brainstorm, how did we deal with a housing crisis in the past?

Ultimately, any increase in prices in Ireland is going to be quite marginal this year, says McQuinn, and we may see prices falling. “But I think over the longer run prices will continue to remain pretty much where they’re at, if not to start increasing again. Because again, we are just not building enough housing at present.”

“It’s obviously very uncertain really, as to where the market is going over the next period of time,” he says. “On the one hand you have these very, very high prices that are correcting after having risen so sharply. Then you have the interest rate compounding that correction at present. Even though we’re building more housing, the demand is still very high. So that imbalance is always going to put upward pressure on prices. It’s just whether the increase in the interest rates is enough to offset that: at this stage it’s a case of, I’m afraid, only time will tell.”

Additional reporting by Alina Trabattoni for the European Broadcast Union‘s A European Perspective initiative.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ