The cost-of-living crisis threatens to tip over into a housing crisis. Prevention is better than cure.

Spiralling housing costs are causing despair across the European Union. Many are anxious they will be overburdened financially. Others have become homeless or live in substandard accommodation. Many young people are unable to leave home.

As a forthcoming Eurofound report on the cost of, and access to, housing in Europe will show, renters in the private market are particularly insecure: nearly half (46 per cent) say they may have to leave their accommodation in the next three months because they can no longer afford it. Private tenants also report problems with the quality of their accommodation—such as poor energy efficiency and lack of space—to a greater degree than homeowners, especially, but also tenants of social housing.

Housing problems are not confined to private renters, however. Homeowners with variable-rate mortgages are having to deal with rapidly increasing interest rates and, more broadly, the rising cost of living. There is evidence of this in Poland, for example, where the Borrower’s Support Fund for mortgage-holders with payment problems has seen a surge in demand. An economic downturn would put even more at risk.

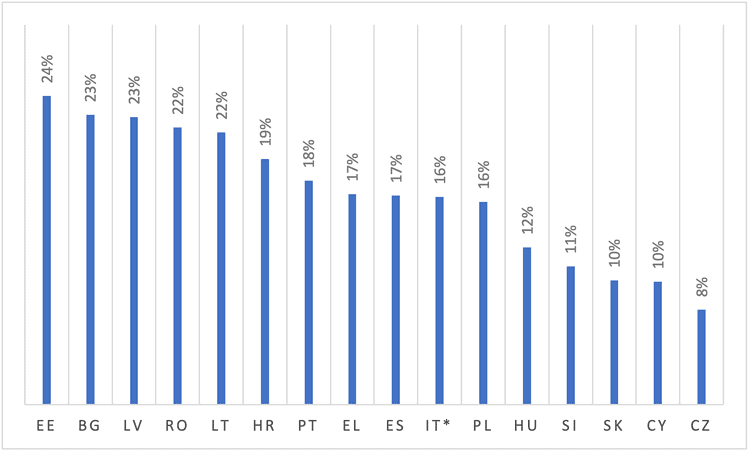

Even among those who own their home without a mortgage, many are struggling to meet other, related costs, such as utility bills. The figure shows the 16 EU member states with the highest rates of outright home ownership (which varies from 38 per cent in Portugal to 95 per cent in Romania). Many of these outright owners are at risk of poverty—from 8 per cent in Czechia to 24 per cent in Estonia. Furthermore, many are unable to maintain their homes at a suitable temperature, due to poor energy efficiency and financial strain: this is true of at least 15 per cent in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Lithuania and Portugal.

Homeowners without a mortgage at risk of poverty, in EU member states with highest rates of ownership without a mortgage, 2020

Compared with homeowners, tenants of social housing on average rate the quality of their accommodation lower and worry more that they might be forced to leave their homes. And they are more likely than private tenants to have difficulty paying for utilities. Comparing those on similar incomes, however, fewer social than private tenants expect problems with these bills, implying that social housing acts as something of a buffer. Nevertheless, many do encounter difficulties and supply of social housing is limited in many member states.

Homelessness on the rise

While some countries have seen homelessness decrease (notably Finland, which pioneered the ‘housing first’ approach), the problem is getting worse in others. In Ireland, for instance, the number in emergency accommodation has increased steadily, from 7,991 in May 2021 to 11,754 in January 2023, with a risk of further increases now that a pandemic-related ban on evictions has been lifted. More generally, the winding down of cost-of-living support measures poses a risk for those households that have depended on them.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Housing support is a tricky area. Support for renting or buying housing can push up rents and selling prices generally. Mortgage support benefits disproportionately those on higher incomes, more likely to buy a home, while encouraging some to take on debt which they cannot pay off. Many dependent on renting meanwhile remain ineligible: those without a fixed address or in shared accommodation, migrants and mobile citizens, those lacking formal contracts and those on low incomes just above the entitlement threshold.

Even among those entitled to housing benefits, some are unaware that this is so or do not avail themselves for other reasons. Nor are social-housing rights always realised: even member states with large stocks have waiting lists.

Expanding supply

By contrast, expanding supply of quality housing puts downward pressure on rents and prices. Homes need to be built and renovated, while the practice of leaving accommodation vacant needs to be discouraged. Improving supply is however a long-term solution and the challenge needs to be addressed in the here and now, and on different fronts simultaneously.

Early warning of payment problems, so that personalised support can be triggered, is fundamental. Sweden, for instance, requires anticipated evictions to be reported to a designated organisation, which approaches the household and provides support to prevent that eventuality.

Access to debt-settlement procedures and debt advice is also key, for those struggling with mortgage payments or accumulating rent or utility arrears. Ideally, again, support is set in motion early, as soon as payments are missed.

Prevention remains better than cure. Policy-makers need to ensure households are not facilitated to take up mortgages beyond their likely repayment capacity. In Belgium, most mortgage rates are fixed and creditors are required to fund debt support, their contributions depending on the proportion of loans with arrears.

Energy efficiency

As to utility bills, more needs to be done to ensure that investments in energy efficiency, which the EU is funding massively through the Recovery and Resilience Facility, reach low-income tenants and homeowners. This will protect households against price increases by decreasing their dependence on external energy—whether because they need less or generate their own.

Housing support should not be seen as separate from other social benefits and services. General social protection, such as a minimum income, and good access to services such as education and healthcare can help maintain the living standards of those who do not have access to housing benefits yet feel the pressure of high housing costs.

To guarantee access to accommodation, stable and independent housing should be provided to those who are homeless or about to become so. ‘Housing first’ policies are effective but they need to be scaled up. About three-quarters of member states have such schemes in place but few have the capacity to house more than 1 per cent of the homeless. And many do not offer housing to individuals who refuse service support or offer shared accommodation, which is at odds with the underlying values.

Europe’s housing situation calls for rapid and effective implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights. Obviously, the rights directly linked to housing play a crucial role here. But so does implementation of the rights to access to quality services and other forms of social protection—key to preventing and addressing housing problems.