By Tom Bill, head of UK residential research at Knight Frank

Borrowers are currently rolling off relatively favourable two-year fixed-rate deals agreed at the start of 2022, but the pain from higher rates will reduce as the year progresses.

Last week’s economic data was reassuringly predictable.

On Wednesday we learned that core inflation fell by fractionally more than expected while services inflation proved slightly more stubborn. Meanwhile, the main headline inflation reading was marginally lower than anticipated at 3.4%.

The Bank of England’s unsurprising response on Thursday was to hold the bank rate at 5.25%.

Given the UK housing market is still in recovery mode after a quiet 2023, no news was probably good news. High mortgage rates and persistent inflation meant transactions fell by a fifth last year and average prices dropped by 5% in the year to September.

The mood turned more positive in the final quarter, as headline inflation fell quickly, and money markets priced in five rate cuts of 0.25% in 2024. However, those expectations have cooled since January as underlying inflation persists and the current forecast is closer to three cuts.

The data has sent the sort of mixed messages that are likely to produce friction between buyers and sellers around prices, as we explored last week.

But how much financial pain exactly will enter the system by the end of 2025 as borrowers roll off fixed-rate deals agreed some time ago on better terms?

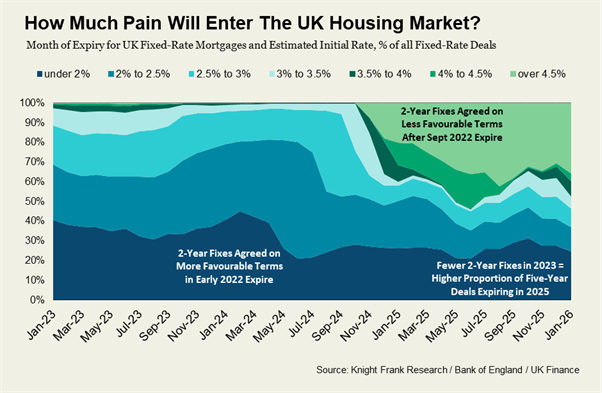

This chart, based on a Knight Frank analysis of mortgage data, provides a good clue.

The figures, which cover purchases and re-mortgages, are based on the monthly proportion of deals taken at different fixed-terms and the corresponding average rate. We also calculated a probable spread of rates based on how many mortgages were taken across the loan-to-value (LTV) spectrum.

The first conclusion is that there are a number of borrowers whose relatively more favourable two-year fixed-rate deals are expiring in the early months of this year.

This is the result of loans agreed as interest rates were in the early stages of climbing at the start of 2022. There were 14 consecutive rate rises between December 2021 and August 2023, pushing the average rate on a two-year mortgage (75% loan-to-value) to 6.18% from 1.57% over that time.

It means that this year, the estimated proportion of all fixed-rate mortgages being renewed where the initial rate was less than 2% will fall from a peak of 45% in February to 26% by December.

By the final months of 2024, the majority of sub-2% deals due for renewal will be five-year mortgages from 2019 (the rest will be three or four-year deals). Sub-2% five-year mortgages will disappear from mid-2027.

Despite more financial pain entering the system, we forecast that UK prices will rise by 3% this year thanks to the greater overall stability in the mortgage market.

It’s also true that as this pain works its way through the system, there will be a growing number of borrowers agreeing a new rate at similar or improved terms later this year. This is the result of two-year fixes taken out when rates spiked following the mini-Budget in September 2022.

By the end of 2024, deals agreed at over 4% will account for a fifth of all fixed-rate mortgages due for renewal. By the end of 2025, the figure will be 33%, according to the estimates.

Meanwhile, the reason behind the increase in deals below 3.5% expiring in the second half of 2025 is that proportionately fewer two-year deals were taken out in the corresponding period in 2023. Variable rate mortgages grew in popularity at the time as borrowers anticipated a peak in the bank rate. At the same time, five-year fixes remained popular among those seeking longer-term stability during a period of rate volatility.

This logic has since altered.

Simon Gammon, head of Knight Frank Finance, said:“Two-year fixed mortgages have become the product of choice again.

“The gap between a two-year and a five-year fix isn’t huge, and many borrowers want to give themselves the opportunity to pick up a mortgage starting with a 3 in two years’ time.”

The lack of a cliff edge moment for mortgage rates is one reason we don’t expect a sudden lurch down in house prices. The prevalence of fixed-rate deals in recent years compared to variable rates means that any financial pain will enter the system gradually. More than 90% of mortgages were fixed-rate in the years before the pandemic.

The relative financial strength of lenders compared to 2008/09 will also prevent large-scale foreclosures.

Not that this overall picture of stability makes it any less painful for anyone taking out a higher-rate mortgage. As the chart shows, there will be more so-called “cold shower” moments for borrowers for a few years yet.