- Every month 150,000 mortgage holders reach the end of cheap fixed deals

- Many find they’re moving to rates that are two, three or even four times higher

- In this six-part series we reveal how British homeowners are coping

Since mortgage rates began rising, many of the nine million mortgaged households in the UK and close to two million landlords have been faced with the prospect of much higher payments.

Before that, many had become accustomed to ultra-low interest rates for more than a decade.

In this six-part series, we look at how much more people are really paying when they take out a new mortgage, how households are coping and if a mortgage crisis is afoot.

Last week, we looked at how much more people are paying when they come to remortgage. Now we investigate how many are finding themselves unable to cope with those higher payments, meaning they face mortgage arrears or even repossession.

Households are spending their savings

How well a household will be able to cope with higher mortgage payments depends to some extent on how much they have in savings.

The amount of savings held by households fell every month last year, according to the trade association for the banking and financial services sector, UK Finance.

This trend was last seen 25 years ago, and suggests that some borrowers might be dipping into savings to meet higher costs, including higher mortgage payments.

Related Articles

HOW THIS IS MONEY CAN HELP

Lee Hopley, director of economic insight and research at UK Finance says: ‘This clearly demonstrates the strain that cost-of-living pressures continue to exert on households.

‘Following the build-up of savings through the period of pandemic-related social restrictions, savings levels are still well above trend.

‘But, whilst it is obviously a good thing that households have these additional savings that they can draw upon now they are needed, this does mask the fact that not all households were able to build up these buffers.’

Households also cut down their unsecured debt. Overdraft levels continued a downward trend, and half of all credit card balances were interest-bearing, which is the lowest proportion since 1995 when UK Finance records began.

Personal loan borrowing also fell in the final three months of last year.

More people are in mortgage arrears

Mortgage arrears are when people fall behind on their mortgage repayments.

The Bank of England’s latest figures showed the value of outstanding mortgage balances with arrears increased by 9.2 per cent in the three months to December 2023, compared to the previous three month period.

Arrears rose to £20.3 billion, which was 50.3 per cent higher than a year earlier.

The proportion of mortgages that were in arrears increased to 1.23 per cent, which UK Finance says is the highest proportion since the final three months of 2016.

Karen Noye, mortgage expert at Quilter, says: ‘The large increase in mortgage rates seen over the last couple of years is really starting to bite for some borrowers and this is unfortunately causing them to fall into arrears, as they simply can’t afford to keep up with their increased payments.’

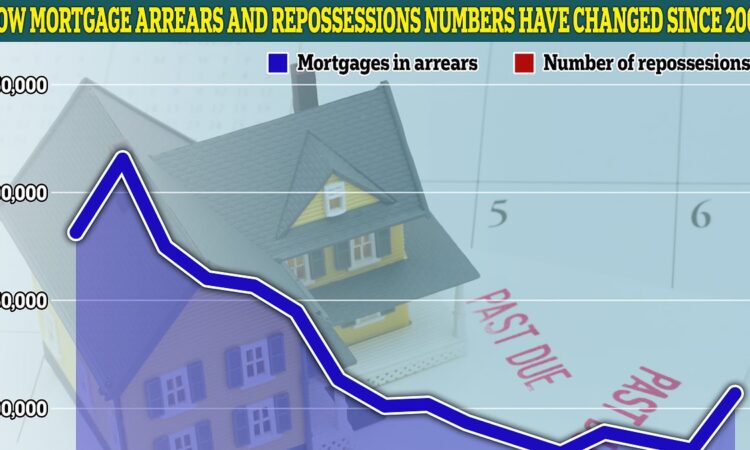

As of December there were 107,250 mortgages with arrears, according to UK Finance. But we are still some way from the levels of arrears seen in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

In 2009. the number of mortgage arrears was roughly double what it is now.

The trade association says that while arrears levels remain low by historical standards, it expects the numbers to continue rising this year.

Are repossessions going up?

A repossession is when a lender takes control of a property after a borrower has defaulted on their mortgage, in order to sell it. This is a last resort after other options have been explored.

In contrast to the increase in mortgage arrears in recent months, the data shows no corresponding rise in repossessions.

The final three months of last year saw 1,150 mortgage repossessions. This number barely changed through the whole of 2023, according to UK Finance.

Leaving aside the pandemic years between 2020 and 2022, the 4,620 repossessions over the course of last year was the lowest number since 1980, when the housing market was half the size it is now.

During the financial crisis in 2009, there were ten times more repossessions – a total of 48,900.

Last year’s repossession figures did represent an 18 per cent increase compared with the 2022 figure.

But according to UK Finance’s Hopley, this was due to delays in the repossession process which were caused by the pandemic.

Hopley says: ‘The year 2022 saw artificially suppressed possession numbers, following the moratorium and issues relating to limited court capacity.

‘So the increase in those numbers last year does not signal a change in market conditions.

‘Rather, it is a timing issue as possessions which, under normal conditions, would and should have taken place in previous years, eventually went through that process.’

Another important point to note, according to Hopley, is that the possessions last year do not relate to mortgage arrears that arose last year.

Hopley adds: ‘Given the substantial backlog, the cases that have been through the process over the last few years relate to mortgage arrears built up some years previously.’

Borrowers opt for more expensive two-year deals

Since rates began surging, two-year fixes have tended to be around 0.5 percentage points higher than five-year fixes.

Currently the average two-year fix is 5.79 per cent compared to the average five-year fix which is 5.35 per cent. Meanwhile, the average two-year tracker rate (which follows the Bank of England’s base rate, plus or minus a certain percentage) is 6.15 per cent.

But last year, the broker L&C Mortgages said roughly half of borrowers opted to fix for two years – despite this being more expensive.

This is because they hoped that rates would come down in two years’ time, and they would be able to get a cheaper rate.

L&C also said that when rates surged, such as in the aftermath of the 2022 mini-Budget, between 20 and 30 per cent of borrowers were opting for tracker rates.

Many trackers are free from early repayment charges, allowing customers to switch as and when they like without paying a penalty.

David Hollingworth of L&C says: ‘Generally, we have tended to see borrowers looking at how they can manage the volatility and keep their options open for a reduction in interest rates further down the line.

‘That saw more borrowers using no penalty trackers during the mini-Budget period so they could still switch to a fixed rate later if they preferred.

‘More recently, borrowers have tended to opt for shorter fixed deals in the hope that rates will come back down and again allow them to mitigate the hike in payments to a shorter timeframe, if they’re right on rate movement.

‘Many will have resisted the possibility of extending their mortgage term where they are not increasing their borrowing which also suggests that they are able and planning to tough things out and hope for better rates to come.’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.