Fed’s Balance Sheet Drops by $626 Billion from Peak, Cumulative Operating Loss Grows to $38 billion: Update on QT

Quantitative Tightening is starting to add up.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

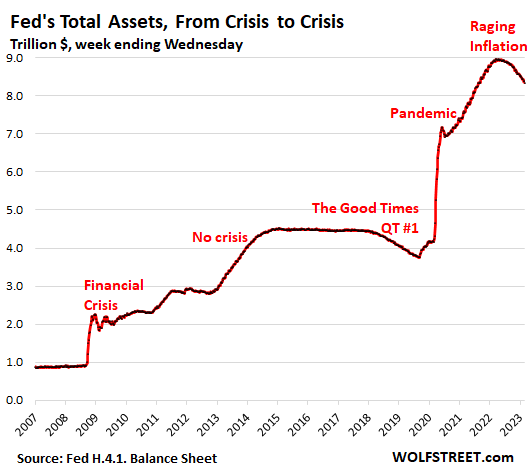

The Federal Reserve has reduced its balance sheet by $626 billion since the peak in April 2022, with total assets now down to $8.34 trillion, the lowest since August 2021, according to the weekly balance sheet released today. Compared to a month ago, total assets dropped by $94 billion.

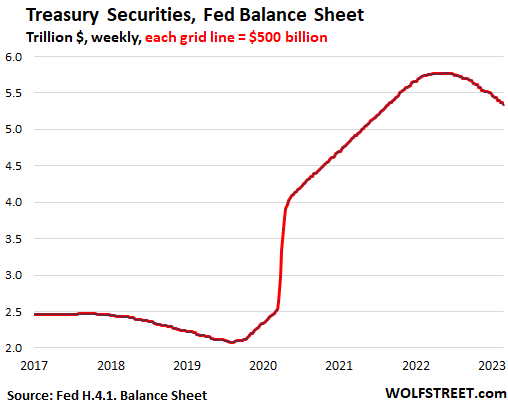

Treasury securities: -$435 billion from peak.

Since the peak in early June, the Fed has shed $435 billion in Treasury securities, bringing the total balance down to $5.34 trillion, the lowest since August, 2021. Over the past four weeks, the Fed has shed $61.2 billion in Treasury securities, exceeding by a smidgen the monthly cap of $60 billion.

Timing: Treasury notes and bonds “roll off” the balance sheet when they mature. Their maturity dates fall either on the middle of the month or at the end of the month. At that point, the Fed gets paid face value for the maturing Treasury securities.

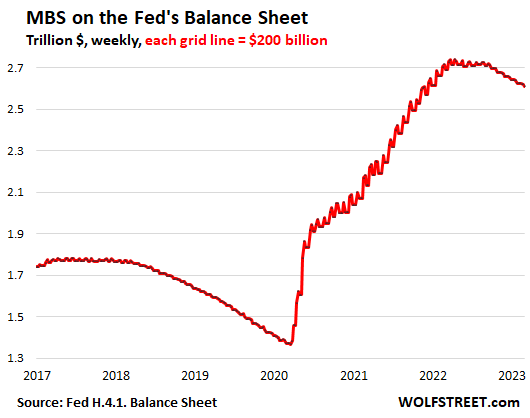

Mortgage-backed securities: -$130 billion from peak.

The Fed’s holdings of MBS have dropped by $130 billion from the peak, to $2.61 trillion. Over the past four weeks, MBS have dropped by $15 billion.

These MBS are all backed by the US government (“Agency MBS”), and the taxpayer carries the credit risk, not the Fed.

The cap for the monthly roll-off is $35 billion. But each month, the roll off has been below the cap, and over the winter by about half. This has to do with the plunge in home sales and the collapse in mortgage refis as mortgage rates have risen.

MBS roll off the balance sheet primarily through the pass-through principal payments that all holders receive when mortgages are paid off, such as when mortgaged homes are sold or mortgages are refinanced. The principal portion of regular mortgage payments are also passed through to MBS holders.

The downward zigs in the chart below reflect these pass-through principal payments that reduce the MBS balances on the Fed’s balance sheet. The upward zags reflect the Fed’s MBS purchases during QE.

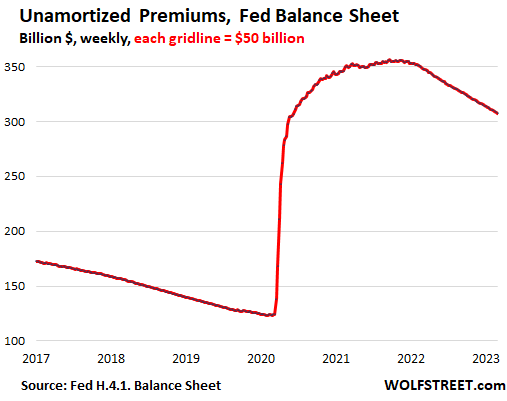

Unamortized Premiums: -$45 billion from peak.

Unamortized premiums fell by $48 billion from the peak in November 2021, to $308 billion. Over the past four weeks, they fell by $3 billion.

Every investor that buys bonds in the secondary market has to deal with this issue when market yields for that maturity are lower than the coupon interest rate of the bond: The bonds trade above face value. This “premium” above face value becomes a capital loss when the bond matures and the holder gets paid face value. That premium is the price paid for the above-market coupon interest payments. So over the life of the bond, it works out. But how do you account for that premium?

The Fed writes off the premium in regular increments over the life of the bond, and by the time the bond matures, the premium has been written off entirely. This amortization matches the higher coupon interest income from the bond with the corresponding write-down of the premium. The Fed accounts for the premiums in a separate account, “unamortized premiums,” and each week, the amortization of the premium reduces this balance:

Keeping an eye on potential warning signs.

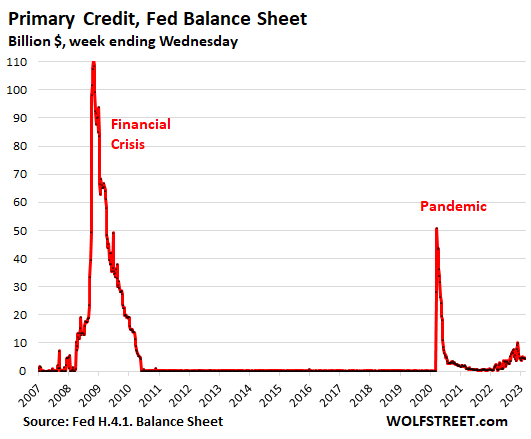

“Primary Credit” – the Discount Window. The Fed lends money to the banks at the “Discount Window,” for which it charges banks currently 4.75% in interest. This is not free money for the banks. They could borrow money for much less from depositors, if they can find depositors willing to accept lower rates on their deposits. They usually can. But when they can’t, the balance of primary credit begins to spike, indicating that at least some banks are coming under some funding stress.

Primary Credit started edging higher about a year ago, as interest rates were rising, and at the end of November 2021 reached $10 billion, which is still minuscule. Since then, the balance has dropped to $4.4 billion on today’s balance sheet. So far, so good:

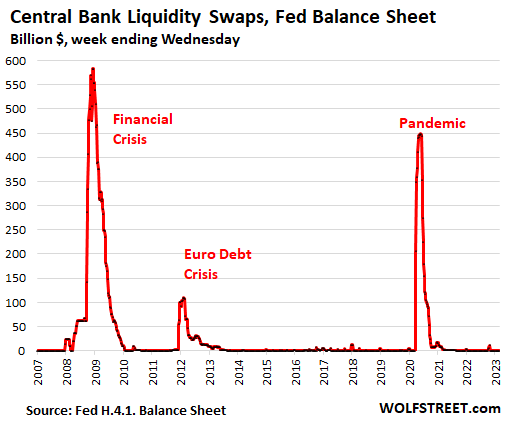

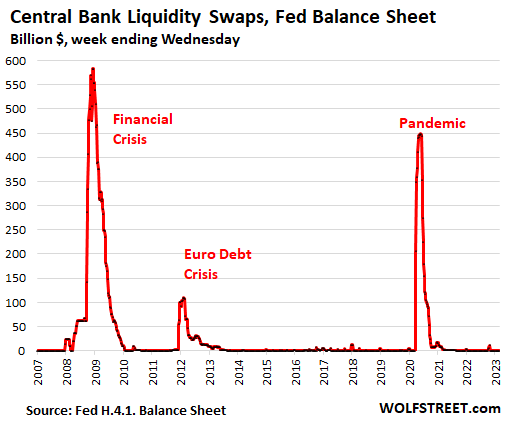

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps. The Fed has well-established swap lines with major central banks, where that central bank can swap local currency for US dollars with the Fed. Swaps have maturities, such as seven days. When they mature, the Fed gets its dollars back and the other central bank gets its currency back. There are currently only $419 million (million with an M) in swaps outstanding. So far, so good:

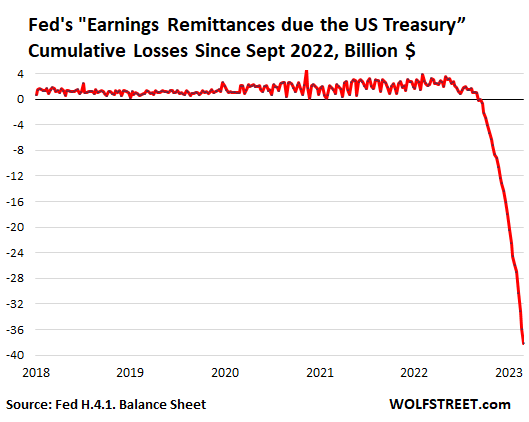

The Fed’s cumulative operating loss since Sep 2022: $38 billion.

From September 2022, when the Fed first started making operating losses, through today’s balance sheet, the Fed lost $38 billion.

The Fed’s trillions of dollars of bond holdings generate interest income. But the Fed bought these bonds when yields were low.

The Fed is paying interest on the cash that banks deposit at the Fed (“reserves”) and on overnight reverse repurchase agreements (RRPs) where the counterparties are mostly Treasury money market funds. But the Fed jacked up these interest rates as part of the rate hikes.

In 2022 up to September, the Fed still had made an operating profit of $78 billion, which it remitted to the Treasury Department, as it is required to do – a sort of 100% income tax. Since 2001, the Fed has remitted $1.36 trillion to the Treasury.

But by September 2022, the interest expense started exceeding the interest income from its bond holdings, and the Fed started having operating losses. The remittances stopped.

The Fed tracks the operating losses in the same liability account, “Earnings remittances due to the U.S. Treasury” (chart below).

At some point, as QT shrinks the reserves and the RRPs, the interest expense begins to decline, and eventually, the Fed is going to make profits again. Those profits will be taken against the cumulative losses in this account. The Fed will not remit any profits to the Treasury until the cumulative losses have all been reversed, and the account starts having a positive balance again.

As a reminder: Losses don’t matter to a central bank that creates its own money. It can never run out of money, obviously, and therefore it can never run out of capital. The Fed’s capital is set by Congress and it has not fallen since the Fed started making operating losses.

So these losses aren’t an issue for the Fed, but the taxpayer misses out on a special QE gravy train, namely the remittances.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()