Viewed from France, where real estate loans are made at a fixed interest rate over 20 or 30 years, the system seems crazy, yet it is widely used. Almost everywhere in Europe – but it is also true in a large part of the world – households are taking out mortgages with fluctuating interest rates, with the risk that their monthly payments will go up as central banks raise their key rates.

This is precisely what is happening with the inflation shock, which has been spreading across the world for the past 18 months. The European Central Bank (ECB) has already raised its interest rate from -0.5% to 2.5% (and will raise it to 3% on Thursday, March 16), the fastest increase since the creation of the Eurozone. The same thing is happening in neighboring countries, including the United Kingdom, Sweden and Central Europe.

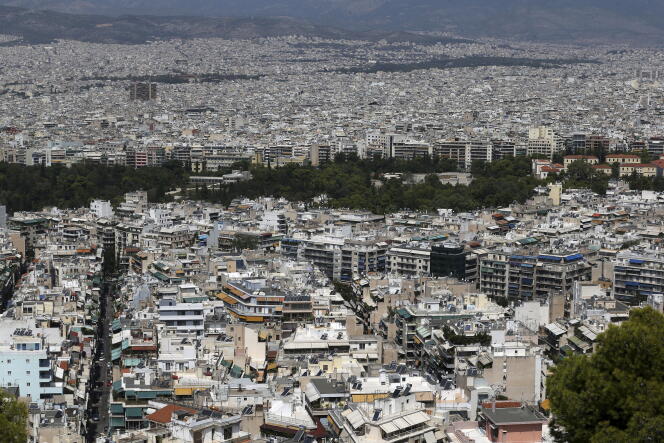

In this context, Europe is divided in two. France, Germany and the Netherlands, which operate mainly with fixed rates, are relatively spared. This is not the case in Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy, where “households are facing higher interest rates and therefore higher repayments and a higher cost of living,” explained Alessandro Pighi, an analyst at the rating agency Fitch.

Two countries in particular are becoming “the canaries in the coal mine,” warned Gilles Moëc, chief economist at Axa insurance: Sweden and the UK. In a recent note, he was concerned about the cold snap in the real estate sectors of the two countries, both of which have entered recession. “Housing is often the first shoe to drop – and then it hurts!” he wrote. In Sweden, home prices, which had been swelling steadily, are already down 12% from their peak. In the UK, the drop since the summer of 2022 is 4%.

But the current situation is nothing like the great financial crisis of 2008, when real estate experienced a global crash. “In the last decade, banks have met much stricter lending criteria, with significant supervision by regulators,” said Pighi. “But to have a real turnaround, there would have to be a sharp rise in unemployment.” And this is currently not the case.

The situation remains no less delicate in many countries: rising foreclosures in Greece, households in difficulty in Spain, a 40% jump in monthly payments in the United Kingdom. In Sweden, a country that wants to be financially rigorous, the political debate even revolves around a possible moratorium on the repayment of home loans.

What is happening in the floating-rate countries, Moëc pointed out, is a harbinger of what is to come in the rest of Europe. “Monetary policy transmission may be swifter, particularly because of the structure of the housing market there, and pain will be felt earlier, but ultimately, the global tightening will end up affecting everyone in the global economy.” The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in the United States, precisely due to the rise in US interest rates, caused major tremors in the financial markets and is a reminder that the context is tense.

You have 84.52% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.