The Bank of England’s governor has repeatedly warned that it will not cut UK interest rates any time soon, even with a recent sharp fall in consumer price inflation.

Like central banks in the US and eurozone, the bank has been sharply increasing its base rate to try to tame a spike in inflation. But this has increased the interest people must pay on loans like mortgages, as well as businesses’ financing costs, leading to an economic slowdown.

Inflation has roared back around the world over the past two years after many years of “low-flation”. A period of slow consumer price growth since the mid-2010s had left central banks struggling for ways to stimulate economic activity. But how they have tackled inflation since have diverged in line with the specific issues and items driving price growth in each economy. Understanding these differences could shed light on the likely direction of interest rates in the coming months.

When COVID hit and lockdown measures stopped the economy altogether, price pressures fell even more than they had during the low-flation period. Some inflation gauges even turned negative. The world’s major central banks used more monetary stimulus to keep their economies afloat. The eurozone implemented the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), while the UK and the US came up with similar measures.

The COVID recession also had a particularly pronounced effect on energy prices – US oil prices even went negative for a few days in March 2020.

But this shock was temporary. As lockdowns eased throughout the western world in the second half of 2020 and into 2021, the economy jumped back quickly. This happened faster and to a greater extent than anyone had anticipated thanks to the stimulus programmes countries enacted.

Diverging fortunes

Of course, since every country didn’t experience this snapback at the same time, global supply chains could not keep up. Production in some countries was still in lockdown, while in others factories were ramping up production as people in recovering countries were starting to buy again. Orders became backlogged and shipments were queued.

These bottlenecks led to shortages and price hikes for many goods – from cars to phones to over-the-counter pain meds and baby formula.

Energy prices also shot up again. Crude oil prices reached pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2020 and surpassed them throughout 2021. So even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, energy prices and the reopening of the economy were pushing inflation up.

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine gave energy prices another jolt, of course – especially natural gas in Europe. This led central banks to argue they were fighting global cost-push inflation. This means external factors were pushing up the prices of key goods, leaving central banks with little control.

But a closer look at the figures shows that the inflation stories in the three major economies of the US, UK and eurozone had already started to diverge at this point. Since then, they have become even more different.

In all three, inflation peaked at close to 10% in the second half of 2022, but the drivers differed. The following charts show the major contributors to overall consumer price inflation in each of these regions were energy, food and then services and other goods.

In the eurozone, inflation was mostly due to higher energy and, later, food prices:

But in the UK the prices of non-energy, non-food items were more important to the inflationary push:

As they were in the US:

The current inflation picture

Now the height of the pandemic is behind these economies, supply chain pressures have eased, and energy prices are back to pre-war levels – hence the fall in inflation that’s now being reported relative to last year.

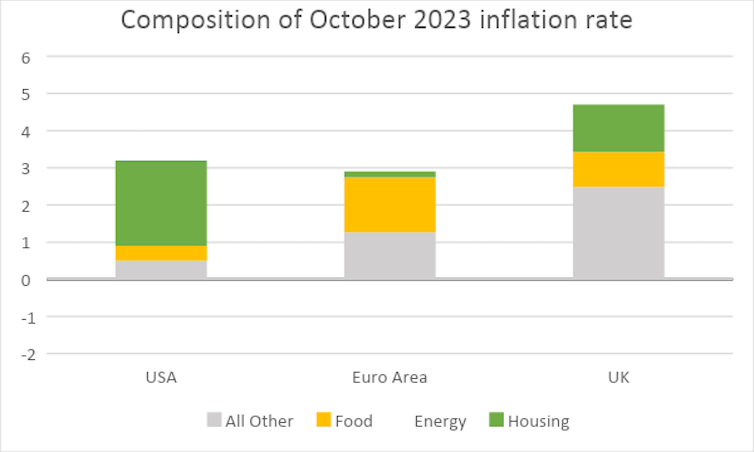

But the latest headline inflation figures (October 2023) show that another item is now causing these three economies to diverge: housing.

The US and the eurozone have similar headline inflation rates. But in the US, inflation is mainly driven by housing costs (which may be partly due to the way housing costs are measured in the US). In the eurozone, however, energy prices are now dragging down the rate of inflation – although that is offset to a large extent by food prices, which have continued to rise.

On the other hand, the UK has a higher inflation rate and the “all other items” category is now the biggest driver of price rises. So, in the UK, price increases across the board mean that inflationary pressures have spread from a few sectors, like energy or housing, to the broader economy. This makes inflation more sticky and requires more policy tightening to cool down the economy.

More interest rate rises to come?

All of this shows that, in the US and the eurozone there is little sign of broad-based inflation pressures at the moment. If energy prices remain constant and food prices stabilise, inflation might soon return to close to the 2% target most central banks aim for, even without further action by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

The UK, by contrast, seems to have a more standard inflation problem with price pressures across a wider set of items that still need to be contained. This leaves the Bank of England with a harder job to do to bring inflation under control.

And so, we can expect inflation to keep slowing in the eurozone and the US without much intervention. In the UK, however, further action might be needed if the Bank of England is to keep price rises under control.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pietro Galeone, Research fellow, Bocconi University and Daniel Gros, Professor of Practice and Director of the Institute for European Policymaking, Bocconi University