Assessing the Incremental Costs of Regulation and Supervision Faced by EU Banks Compared to Their US Peers

2

By Leticia Rubira, Engagement Manager, Public Sector and Policy Practice, and Oliver Wünsch, Partner, Sovereign Finance and Public Policy, Oliver Wyman

By Leticia Rubira, Engagement Manager, Public Sector and Policy Practice, and Oliver Wünsch, Partner, Sovereign Finance and Public Policy, Oliver Wyman

Oliver Wyman recently published a reference study, commissioned by the European Banking Federation (EBF), on the impacts of the EU banking regulatory framework on European banks and economies. The report has spurred a debate on the role regulators, supervisors and banks should play in fostering financial stability and growth, while also acknowledging that banking and regulation operate within a broader economic-policy context and recognising the risks and constraints emerging from this.

≈≈≈≈≈

The availability of financing is instrumental in enabling the transition to a more competitive and sustainable economy. Given the vital role of banks in unlocking such financing, ensuring the regulatory and supervisory impacts on financial institutions are adequate, both from a financial-stability and growth perspective, should be high on policymakers’ agendas. Our recent reference study,1 commissioned by the EBF, aims to bring this discussion to the table. Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the European Union’s (EU’s) banking sector has trailed behind the United States’ and is nowadays, on average, not earning its cost of capital. Healthy profitability is the first line of defence and a prerequisite for banks’ abilities to attract investors and raise capital if needed—very much required to enable them to realise their core function: financing the economy.

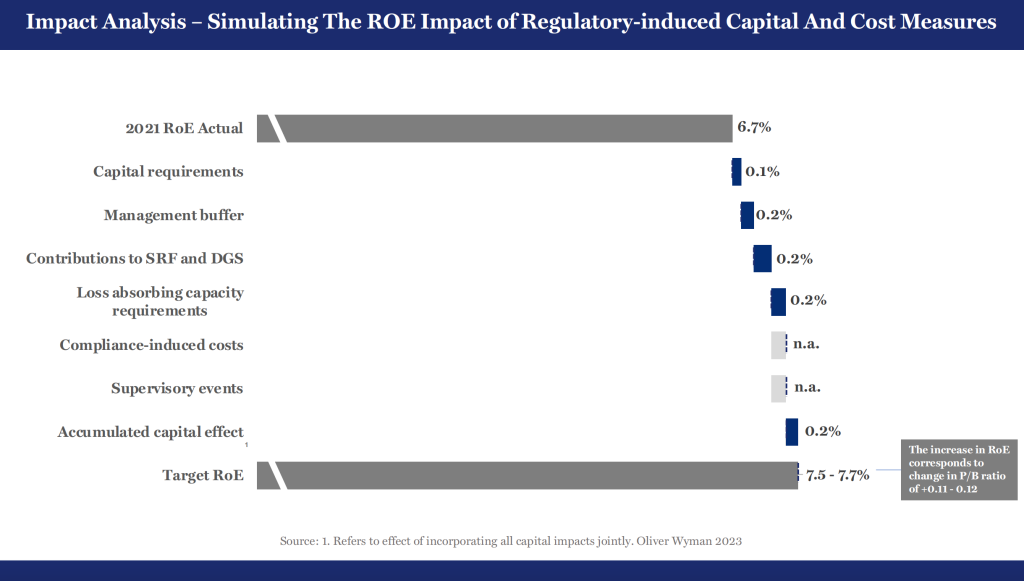

In our study, we strived to provide a holistic and independent assessment of the regulatory and supervisory costs for EU banks compared to US banks, accounting for structural differences between both regions. We have concluded that the incremental difference in regulatory-induced costs at EU banks compared with their US peers can explain 0.8-1.0 percentage points of the return-on-equity (ROE) gap between the banks of the two regions. This difference is mostly driven by Europe’s more complex capital-requirement framework, which is also perceived as less predictable; higher contributions to the safety-net architecture; compliance requirements; and resource-intensive supervisory processes.

On the capital-requirement front, the main takeaway should not be that requirements are on average higher in the EU than in the US; one also needs to account for different business models and balance-sheet structures and the regulatory objective of keeping the banking system safe and sound. Rather, the aim of making the EU’s regulatory framework more granular and having supervisory approaches based on stringent methodologies made them, in fact, more complex and provided for wider supervisory discretion than in the US. There, a single stress capital buffer (SCB US) contrasts with the methodologically elaborate but less pragmatic approach of having multiple, partially overlapping requirements and buffers imposed by EU and national supervisors. This complicates the capital-management efforts of EU banks and is one of the reasons why EU banks are more prone to hold higher management buffers than their US peers.

Additionally, the costs associated with the European safety net (deposit insurance and resolution funds) impose a considerable burden on banking union banks. Since the Global Financial Crisis, the EU has established an elaborate multi-institutional structure to break the sovereign-bank loop while staying within the constraints of the eurozone’s monetary and fiscal architectures, providing limited risk sharing across the Union. EU banks today face the costs associated with building up the safety net, as opposed to simply maintaining it. Furthermore, the EU has targeted a higher coverage rate (2.4 percent of covered deposits, compared to 1.35 percent in the US) and, from the perspective of building bail-in capacity, a higher target for bail-in-able instruments, with a wider scope of application.

Compliance and supervisory requirements have become increasingly resource intensive across both Europe and the US. In terms of compliance, the main cost driver in Europe is the high pace of regulatory reforms in recent years, leading to recurring change-the-bank costs. Member states typically retain some discretion on compliance-related topics, leading to disparities between countries and consequent needs to comply with local-market standards in preparation for closer scrutiny of national regulations—something that is also an issue that drives costs and the complexities of compliance-related processes for those banks that operate in the EU and the US simultaneously.

But it is not only the rules that make the difference. Supervisors across the globe retain significant discretion in how they design the processes to implement these rules. The EU supervisory interaction is perceived as being relatively formalistic, with an exhaustive review relying on frequent on-site examinations and demands for ad hoc analyses and measures—compared to the US supervisory process, which relies on more standardised outputs, continuous interactions and bank-led processes. This is partially driven by the fact that particularly at the inception of the SSM (Single Supervisory Mechanism), there were different degrees of maturity levels across the EU banking sector, and the need for harmonisation and establishing a level playing field was of utmost importance. Ensuring banks had adequate arrangements as well as capital and liquidity gave more relevance to “qualitative” elements and horizontal reviews—also considering the heterogeneity of the EU economy.

All that said, it would be a mistake to believe that banking regulation is the main driver of the differences in performance between US and EU banks. In the end, the fate of banks is closely connected to the economy’s well-being and the overall economic policy. The same applies to regulatory and supervisory strategies, which need to pay significant attention to broader economic risks. Unfortunately, the economic conditions to which EU banks are exposed in their home markets have not been favourable in the years since the GFC. The eurozone was hit by the European sovereign debt crisis, exacerbating the impact of the GFC and restricting fiscal capacity, while US public policy after the GFC allowed US banks to stabilise and recover more quickly. Additionally, compared to the US, eurozone growth has been slower, leading to fewer lending opportunities. Furthermore, the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) highly accommodative monetary policy led to lower interest rates for longer, compressing NIMs (net interest margins) and hitting the net profitability of lending businesses, the main revenue driver of EU banks.

Structural factors, such as market fragmentation and less vibrant capital-market limits as a result of historical developments and slow convergence, have put the EU financial sector at a disadvantage compared to its US peer. The banking sector in the EU is much less concentrated than its US counterpart and is thus facing higher competitive pressures and more limited potential to benefit from economies of scale. Impediments to liquidity transfers within banking groups across member-state borders remain—also due to the incomplete integration of safety nets, making truly pan-EU business models expensive from a capital and liquidity perspective and, therefore, less attractive.

EU and US banks operate with different business models, influenced by the deep capital market of the US. The prevailing business model for banks in Europe is that of a universal bank that retains loans on its balance sheet in the long run, often until full repayment is made. In contrast, US banks can leverage the US’ deep capital markets in their lending businesses. For secured lending, such as mortgages, US banks employ an originate-and-distribute model, through which loans are quickly securitised and placed into financial markets. In a hypothetical scenario in which EU banks could transfer half of their current mortgage portfolios to non-bank investors, banks’ CET1 (Common Equity Tier 1) ratios would increase by around 0.9 percentage points, and banks’ lending potential could increase by about EUR 0.9 trillion.

The differences between jurisdictions, while many, should not undermine the conclusions of the report on the basis of limited comparability. Forward-looking and constructive dialogue between banks, EU regulatory authorities and policymakers on the directions of regulatory and supervisory measures and the broader economic environment is essential. Banks play an important role in providing funding to the EU economy, with 70 percent of corporate borrowing being intermediated by banks—as opposed to the US, where 77 percent of corporate funding is provided through capital markets.

The report suggests that a review of current capital requirements and supervisory processes could free up capacity for approximately EUR 4.0-4.5 trillion of additional lending in a best-case scenario, representing an increase of almost 30 percent compared to current bank-lending volumes. This lending boost would need to be assessed against the eurozone economies’ practical abilities to absorb additional funding without marked increases in banks’ risk profiles or any potential associated financial-stability risks, especially in a recessionary environment. The availability of private-sector and bank financing will be crucial to supporting green and digital transitions and improving the European economy’s competitiveness.

While the scope of our mandate did not include defining and recommending remedial actions, our report demonstrates that policymakers should redouble their efforts to complete the banking and capital-markets unions, and they should also simplify the current complex and costly resolution regime. Supervisors should place greater emphasis on streamlining key processes and making them more efficient while remaining vigilant in ensuring that EU banks are not placed at a disadvantage within and outside of the Union. Banks are the cornerstone of materialising policy objectives. They should position themselves for the long-expected process of consolidation and engage in more programmatic risk-transfer solutions, with private investors as strategic tools to manage bank capital and risk in order to strengthen the Union. All that said, both banks and their regulators act within a broader economic context that comes with constraints and risks. A healthy, innovative and growing economy is the precondition for financial intermediation to thrive without creating undue risks to financial stability.

References

1 Oliver Wyman: “The EU Banking Regulatory Framework and Its Impact on Banks,” Oliver Wuensch, Kai Truempler and Leticia Rubira, full text of the study.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of Oliver Wyman.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Oliver Wünsch is a Partner in Oliver Wyman’s Financial Services and Public Policy practices based in Zurich. For more than 20 years, he has worked at and with governments, central banks, supervisors, supranational institutions and private-sector firms, advising on various aspects of sovereign finance and financial and monetary policy.