State DOTs are spending far too much of their most flexible federal infrastructure dollars on highway expansions — and unless they shift that money to sustainable modes fast, it will have dire implications for the climate crisis, an alarming new analysis finds.

As part of their decades-old and entirely useless quest to reduce congestion by widening roads, state departments of transportation have so far used roughly a quarter (24.5 percent) of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s “formula” funding on highway expansions — despite the fact that a century of research shows that doing so simply doesn’t work, and agencies could shift up to 50 percent of that money away from auto-centric uses entirely.

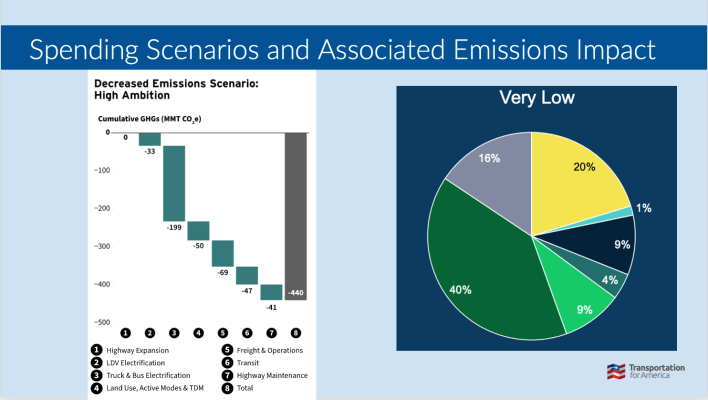

And because formula grants make up nearly half ($270 billion) of the infrastructure law’s $600 billion for surface transportation across five years, the climate impact of all those expansions will be colossal. If DOTs continue pouring asphalt at the same rate until the bill expires in 2026, they’ll increase emissions by more than 180 million tons of CO2 equivalent above the national baseline, according to preliminary estimates from Transportation for America.

That’s roughly equal to running 49 coal-fired power plants for an entire year — and it’s easily enough to overwhelm any emissions reductions that will be made under the infrastructure law’s more explicitly climate-focused discretionary grant programs, which comprise just a tiny percentage of its total funding.

Put another way: the legislation that the Biden administration once promised would “strengthen our nation’s resilience to extreme weather and climate change while reducing greenhouse gas emissions” is poised to do the opposite — at least if the state agencies don’t radically change how they spend the money. And advocates aren’t optimistic they’ll do so without a massive public outcry.

“There’s an old adage that if your job depends on you not knowing something, you’re not going to know it,” Chris Rall, Transportation for America’s Outreach Director, said in a webinar about the new findings. “And there’s just a whole industry of … state departments of transportation — some are still called state highway departments — who are in the business of building highways. If it gets out that there’s this whole induced demand issue, that all this widening of highways isn’t actually going to solve congestion … then they’re going to be out of a job.”

Even worse, state DOTs’ collective appetite for highway expansion is more voracious than many advocates feared. Last year, for instance, the Georgetown Climate Center and the Rocky Mountain Institute modeled the climate impacts of various ways that agencies could split up their formula grant budgets between highway expansions and other uses; in real life, though, DOTs spent 2.5 percent more on expansion than the analysts assumed they would under their worst-case “high emissions” scenario.

Even that depressing number might be an undercount. Because some DOTs erroneously classify highway expansions under other categories like “resurfacing” initiatives, Transportation for America’s analysts are still weeding through tens of thousands of projects to find widenings disguised as other types of projects — and with more than 55,000 projects already reported and roughly 61 percent of formula dollars yet to be obligated, that process could take a while.

However the math shakes out, though, advocates say it’s already clear that highway expansions don’t make climate or fiscal sense — and it’s time for states to put their flexible funds to better use. For instance, states could spend formula dollars to cover transit agencies’ capital budget needs, like building bus lanes and replacing vehicles, in order to free up less-flexible transit agency funds to cover sorely-needed operating expenses, like hiring more drivers.

“Highways are not, in fact, paying for themselves,” said Chris Van Eyken, director of research and policy for TransitCenter. “If other modes were treated the way highways were, they would continuously see government infusions. … I wouldn’t say highways are not facing fiscal cliffs; it’s just that we don’t ever expect to get to the point where we’d stop building them. We always come to their rescue — and we don’t come to the rescue of public transit or biking or walking.”

When the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act expires in two years, of course, America could throw a lifeline to other modes — and Van Eyken says “the time for organizing [for the next federal transportation bill] is now.” In the meantime, though, it will be up to communities to band together and demand that their state DOTs stop the highway-expanding madness and start spending their money more sustainably. Because without that public pushback, there’s little to stop agencies from firing up the bulldozers to add more lanes.

“The National Environmental Policy Act … is more like a series of boxes to be checked, rather than, ‘If you exceed X threshold in terms of environmental impact, you can’t build this project,’” said Ben Crowther, policy director for America Walks. “So lawsuits end up being more like delaying tactics — tactics to get increased public participation, to mobilize folks who are against these projects to show up and put public pressure on their political leaders. That’s really been one of the most effective ways of stopping highway projects.”