Mustafa Nayyem lived through a Russian invasion as a child. Born in Kabul in 1981, he, his father, and younger brother were forced to flee Afghanistan in 1989 after the Soviets withdrew from the country following a disastrous 10-year occupation. (His mother died when he was young.) The family eventually settled in Kyiv in 1991. After experiencing a second Russian full-scale invasion in 2022—he was put on a Russian kill list as Moscow’s troops threatened Kyiv—he is now in charge of making sure that Ukrainians have a home to return to as head of the country’s nine-month-old reconstruction agency.

“My father had to emigrate from his country when I was 8. My son was 12 when the full-scale [invasion] started. I think it’s very obvious that we don’t want to lose our second motherland,” he told Foreign Policy during an interview in his sparsely appointed office in the Ministry of Infrastructure in Kyiv. He and his team only moved in a few weeks ago.

The scale of the country’s wartime destruction is staggering. In March, the World Bank estimated that Ukraine will need more than $411 billion over the next decade to rebuild. The bank calculated $135 billion in direct damage to infrastructure and buildings, which did not include the broader economic costs of destroyed factories, grain depots, infrastructure, and other facilities. The Kyiv School of Economics Institute estimated the damage to Ukraine’s housing stock alone at $54 billion and counting as of the end of May.

Ukraine has also experienced massive losses of human capital. According to the United Nations, there are more than 6.2 million Ukrainian refugees living abroad. Many of these people are highly educated and young: A recent survey of post-invasion Ukrainian migrant adults in Poland and Germany conducted by the EWL Migration Platform and the Centre for East European Studies at Warsaw University showed that more than 70 percent had at least some higher education and a little over half were between 18 and 35. The U.N. has also estimated that Ukraine has suffered more than 26,000 civilian casualties, including over 16,000 injuries. While Kyiv does not release military casualty numbers, U.S. officials estimate that 70,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed and 100,000 to 120,000 wounded. A report published by the European Commission in March estimated that Ukraine’s population could drop from around 43 million on the eve of the invasion to about 30 million in 2050 in a worst-case scenario.

- Tetiana Bezatosna visits her destroyed apartment in a residential building heavily damaged by Russian strikes in Kharkiv, Ukraine, on Aug. 6. Sergey Bobok/AFP via Getty Images

- Refugees from Ukraine receive food in a cafeteria at a refugee registration center at the former Tegel airport in Berlin, on Dec. 9, 2022. Sean Gallup/Getty Images

The quality of reconstruction will make or break Ukraine’s future. If reconstruction goes well, then it will provide Ukrainians—including veterans, returning refugees, and internally displaced persons—with jobs, housing, and schools to build their lives in Ukraine. If it goes poorly, then Ukraine will see further outflows of people into the European Union, where countries like Poland and Germany face labor shortages and already provide Ukrainian refugees with security, schools, power, and water. The former scenario could see Ukraine turn into a European economic dynamo similar to post-World War II West Germany or post-communist Poland, while the latter would see it turn into a declining war-torn country like Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Appointed as head of the State Agency for Restoration and Infrastructure Development in January, Nayyem and his team—including several hundred in Kyiv and others at 24 offices across the country—have been working days, nights, and weekends to ensure that Ukrainians living in areas destroyed or damaged by war get water, power, and heat—and ultimately housing, schools, and jobs. He said that the mission to bring people back was not only the mission of his agency but the “mission of our country, because I think that the biggest damage we have at this moment is [to] people.”

A major challenge facing Nayyem is that many Ukrainian families are separated. For instance, a father might have gone to the front line to fight, while a mother and children are living in the EU. Under martial law, most men between the ages of 18 and 60 cannot leave Ukraine, but when the war ends, these families will be deciding whether to reunite in the EU or Ukraine. This question is fraught. Vadym Denysenko, a former advisor to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and recent executive director of the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, caused a firestorm on Facebook last month after he suggested maintaining the ban on men leaving for at least another three years after the war to ensure that Ukraine would “survive as a nation.” (The Ministry of Internal Affairs distanced itself from his comments, noting that he no longer worked there.)

While acknowledging that some Ukrainians would emigrate, Nayyem made the case for staying. “Imagine the guy fighting on the front line for a year and a half,” he said. “I can’t imagine that when war will end, they will leave everything and go outside [Ukraine].” He added that the postwar period would be a significant opportunity for people in different professions. “We need designers, experts, lawyers, [people in] finance, ecologists, sociologists, project managers, and engineers,” he said. “But also we should have literally people who can work with their hands.”

This vision is dependent on the international community guaranteeing security for Ukraine, he said, calling it the “zero point” for rebuilding. That would be NATO membership or a “very real” security guarantee, “because we had a very bad experience with the Budapest Memorandum,” the 1994 agreement among Britain, Russia, Ukraine, and the United States that prohibited Russia from using or threatening force against Ukraine in return for Kyiv giving its Soviet-era nuclear weapons back to Moscow.

Prior to joining the Ministry of Infrastructure in 2021 as deputy minister, Nayyem had a career as an anti-corruption journalist, activist, and reformist lawmaker. In 2009, he received national attention for publicly questioning then-presidential candidate Viktor Yanukovych about his luxurious estate, Mezhyhirya, on the Dnipro River north of Kyiv. In a Nov. 21, 2013, Facebook post, he urged people to get out onto the streets to protest Yanukovych’s halting of EU accession negotiations with the rallying cry, “‘Likes’ don’t count.’” After the Maidan Revolution concluded in early 2014, he entered politics as a member of parliament in the party of the new president, Petro Poroshenko, but formally withdrew from the party in 2019 due to disillusionment over the lack of progress on anti-corruption reforms.

Given his bona fides, Nayyem is determined not to let Ukraine’s oligarchic corruption get in the way of reconstruction. “When there is big money, there are big risks, and big money needs to be controlled,” he said. “A human being is weak; they can have some problem[s]. The point is how we are going to react to that.” He said that his agency’s work—including tenders, contracts, and plans—are publicly available online for civil society and journalists to scrutinize.

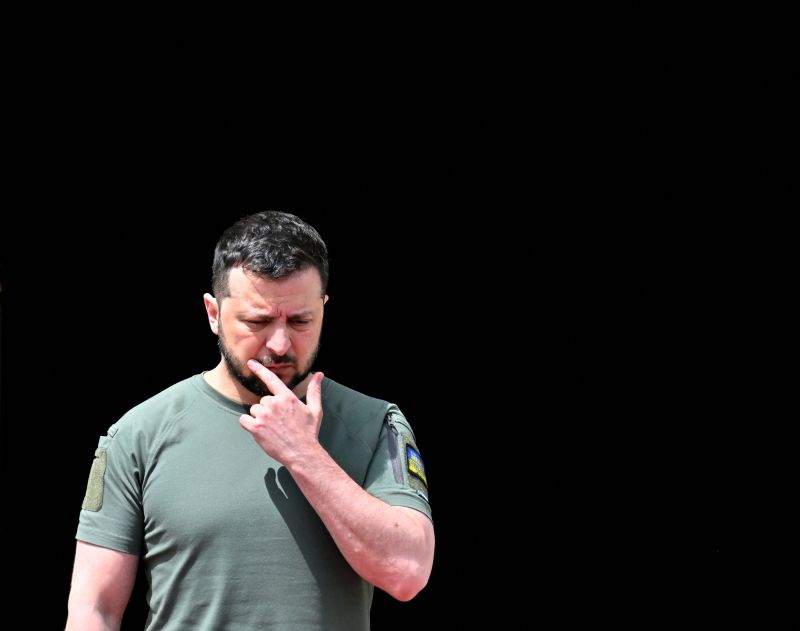

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak introduces Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky onscreen on the first day of the Ukraine Recovery Conference in London on June 21.Henry Nicholls/ AFP via Getty Images

Nayyem’s office coordinates massive inflows of foreign money earmarked for rebuilding Ukraine. At an international conference in London in June, foreign donors pledged to spend $66 billion on rebuilding Ukraine—with $55 billion coming from the EU and most of the rest from Britain and the United States. Nayyem said just before the conference that it would be “very difficult” for Ukraine to absorb this money, since the maximum it had previously received was $6 billion in a year. However, speaking in his office, he added that no country had rebuilt on this scale before with foreign money. “There is no other country in the world which has this amount of government contracts for restoration and rebuilding which we will have in future years,” he said.

Given the large inflows of foreign money and Ukraine’s reputation for corruption, how would Nayyem ensure that reconstruction does not turn into a similar debacle as the one that plagued his home country’s reconstruction following the defeat of the Taliban in 2001? He rejected the comparison of rebuilding Afghanistan to Ukraine. Afghanistan had to build a new state, he said, whereas in Ukraine, the state did not fail and has kept functioning under the strain of a brutal Russian invasion. He noted that the reconstruction agency grew out of successful efforts to keep Ukrainian infrastructure—including energy, transport, logistics, and food production—going in 2022.

In fighting to create a promising future for Ukraine, the Nayyem family has suffered the costs of war. His younger brother, Masi, became a soldier and was deployed following the 2014 invasion as well as in 2022, and he remains on active duty. In June 2022, Masi lost his right eye as a result of wartime injuries. On the second anniversary of their father’s death this past May, Mustafa Nayyem posted a Facebook photo of the two brothers before the injury. He wrote: “But I still can’t take in my brother without an eye, it still hurts.”

Mustafa Nayyem said there was no reason for him to feel “proud” of the long hours he is putting in on behalf of Ukraine’s reconstruction because they didn’t compare to the conditions for front-line soldiers. “I’m sitting in a cabinet [office] in Kyiv and I have light,” he said. “Those people who are now on the front line don’t even have hours for sleeping.” Nevertheless, he keeps going. Earlier this month, he posted a photo on Facebook of the Kyiv sunrise at 7:07 a.m. from his office at the ministry. “We will break through. There is no other option,” he wrote.