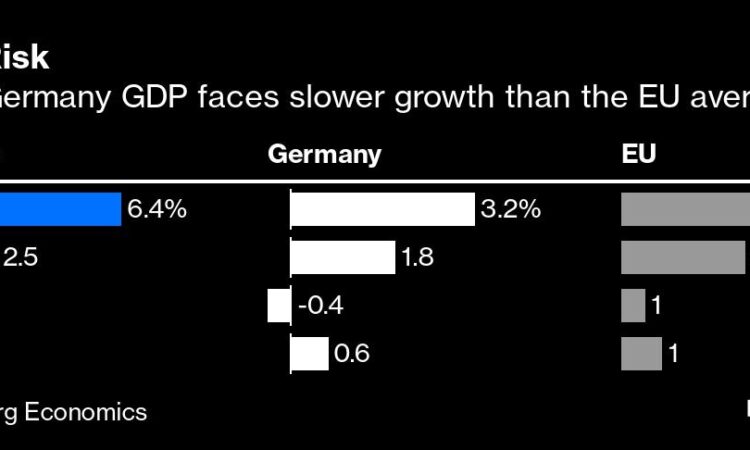

The leaders are very much in the same boat (pun intended). A rising far right is no longer just a French phenomenon, with support for Alternative for Germany (AfD) surging amid anger over migration and the impact of the Ukraine invasion. Their economies are slowing, with Germany’s in particular crushed by a decades-long reliance on Russian gas, while France’s also is sputtering even as inflation starts to ease. They both support more state aid and a less naive approach to trade. Macron is hamstrung by his lack of a parliamentary majority; Scholz struggles to be heard above coalition infighting.

Yet despite this week’s friendly handshakes and solid show of support for Israel after Hamas’ attack, the two men are furiously paddling in opposite directions. The confusion and shock inside Germany over the return of the “sick man of Europe” tag after years of export-led success has seen Berlin scramble to defend its turf — protecting combustion-engine cars, exports to China and energy-intensive industry. That has run up against Macron’s preferences for nuclear power (which Germany fully dumped in April), more pooling of EU defense and more flexible budget rules; Paris’s priorities are sharper and tainted by schadenfreude. Germany’s economy minister, Robert Habeck, said last month: “We agree on nothing.”

Energy policy is a case in point. The impact of the Russian gas shock on electricity markets saw widespread appetite for state intervention, with wholesale electricity prices rising 254% in France and 210% in Germany between the second quarters of 2021 and 2022, according to Jacques Delors Institute researcher Phuc-Vinh Nguyen. But whose intervention? Paris wants to use new long-term power contracts to reap the benefits of nuclear power’s dominance in France, where prices are now 12% cheaper than across the Rhine. Berlin fears including existing nuclear fleets will disincentivize investment in renewables and help French industry while Germany feels the pain of costlier gas. Macron — worried about Marine Le Pen making populist hay out of anti-nuclear Germany — has shown little sign of backing down, pledging Brexit-style to “take back control” of prices.

This is all pretty gloomy stuff for the European project, which is in dire need of unity as it eyes more enlargement, autonomy and energy security as gas prices start to pick up again. It’s also a far cry from past power couples like Charles De Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer or Valery Giscard d’Estaing and Helmut Schmidt, who were better able to smooth over long-running misunderstandings such as Germany’s attachment to the NATO security umbrella or France’s clinging to its world-power status. When the Franco-German engine stalls, so does the EU.

Former French ambassador Claude Martin, whose new memoirs detail the ups and downs of the Franco-German relationship, tells me: “Every time things go wrong, we tell ourselves the engine will start again … But we’ve grown used to not understanding one another.” The spirit of the €800 billion ($850.7 billion) pandemic recovery fund launched by Macron and Angela Merkel seems gone for good.

In the short term, there is some hope that efforts to unlock the specific issue of electricity-market reform will pay off, with Green Party politician Sven Giegold recently touting a “grand bargain.” That might mean Paris finds a way to support its industry via state operator Electricite de France SA while also granting Germany concessions elsewhere, such as by unlocking more cross-border energy infrastructure projects in hydrogen. Rather like the squabbles over an EU taxonomy labeling energy sources as green, which ended up including both nuclear and gas to placate France and Germany, this looks like one of those fights where both sides get their way — ideally without permanent market-distorting subsidies.

However, reconciling Scholz and Macron in the longer term would need 50 boat trips rather than one. Better for Paris to shift its own approach by seeking to build stronger ties with other EU members, rather than spinning out more Franco-German initiatives from drones to battle tanks (or a European aircraft carrier). Meanwhile, Germany should also step up and realize that France and Europe lie at the heart of healing its sick-man status, as a recent paper co-authored by Nils Redeker of the Hertie School points out: The road to energy competitiveness, industrial policy and more exports runs through a stronger and more integrated EU single market. “France and Germany should stop tiring themselves out with head-on fights,” says AXA Group Chief Economist Gilles Moec.

Another Hamiltonian leap looks like a distant prospect; but a steadier boat ride next time would be progress.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

• Telling Nations Not to Be Poor Is Bad Climate Tip: Mark Gongloff

• Ireland’s Economy Is Like a Billionaire Tech Bro: Lionel Laurent

• Did James Bond Have a License to … Globalize?: Max Hastings

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist writing about the future of money and the future of Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for Reuters and Forbes.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion