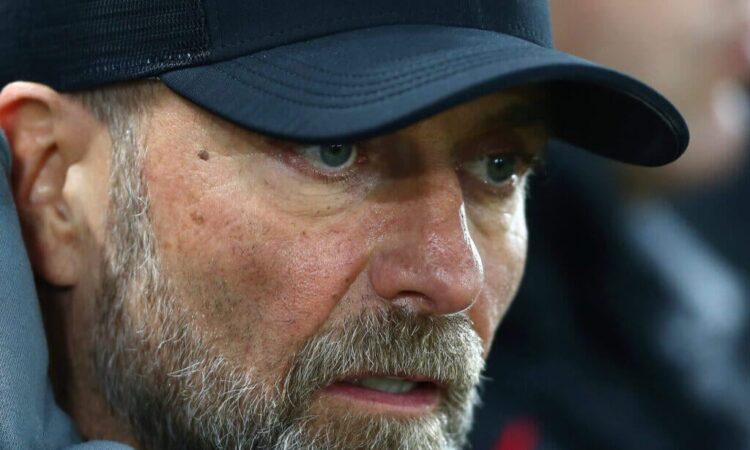

In all the drama of Liverpool’s 2-2 draw with Arsenal last weekend, there was the realisation that even the faintest hopes of qualifying for the Champions League had abandoned Jurgen Klopp’s side.

The gap to the top four has been allowed to grow again and now even the most optimistic Liverpool supporters have been forced to accept a six-year unbroken run in Europe’s elite competition is over.

A dismal season, in truth, saw to that long ago.

Liverpool face a fight to secure any sort of European football in 2023-24 and for that, there will be a price to pay. For the first time since 2016-17, there will be no Champions League money coming to Anfield next season and Liverpool’s turnover cannot escape the hit that is coming.

Klopp’s side have also admitted defeat in their attempts to sign Jude Bellingham, the Borussia Dortmund and England midfielder who would cost around £130million ($162m) plus wages and agent fees.

The deal stopped making sense for Liverpool when the Champions League shortfall and the wider scale of this summer’s rebuild were taken into account.

Then there’s the question of how to attract one of the best young players in the world without the lure of playing in Europe’s elite club competition. Liverpool are also reluctant to pin all their hopes on one footballer — even if Dortmund could have been persuaded to sell — when numbers are needed in midfield as well as defence.

Don’t forget too that the club’s owner, Fenway Sports Group, is still exploring bringing in extra investment. Resources are finite.

The Athletic analyses where a disastrous season leaves Liverpool ahead of the summer transfer window.

How much do Liverpool make from being in the Champions League?

A good old chunk. More is taken annually from the Premier League pot (£152million last season, for example) but since 2017, Liverpool have made roughly half a billion pounds through Champions League distribution money alone.

UEFA’s annual financial reports are published every March and the last five seasons on record detail that Liverpool have earned £422million from their exploits in the Champions League.

Last season’s adventure to the final brought in €119,957,000 (£106m; $131m). Although this campaign’s figure will have dropped after Liverpool were eliminated in the last 16 by Real Madrid, the latest payout from UEFA is still expected to be around the £71million mark.

Liverpool’s recent successes in the Champions League also grant them a bigger slice of the pie. The higher a club’s coefficient ranking — the system that decides how both clubs and their associations are ranked for every season of European football — the greater the benefits. Tottenham Hotspur also exited in the round of 16 but Liverpool will bank as much as £8million more due to UEFA’s distribution being partially weighted in favour of recent achievements in the competition.

And that is not all. Matchday revenues have also been boosted by those Champions League nights at Anfield.

Last season’s accounts showed that £87million had been earned from the 30 home games played since 2017, suggesting that every fixture staged is worth somewhere between £2.5million and £3million. Liverpool have played at least four home games in the Champions League in each of their last six seasons, with sellout crowds as good as guaranteed.

Qualification to the Champions League never brings a specific lump sum but Liverpool’s habit of going far has come to make European football an important revenue stream.

Take last season’s numbers as an example. The £105million earned in prize money from UEFA alone amounted to 17 per cent of Liverpool’s record-breaking total turnover of £594million. Seeing that disappear leaves a significant hole in the balance sheets.

“The figure any club earns depends on how far they go in the competition but even if you just made the group stages and nothing else, that’s minimum £50million for an English club with the way the prize money is set out,” says Dr Dan Plumley, a sports finance expert and lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. “That can then go up to £100m if you go a long way.

“Then you’ve got the other things that come with a Champions League season, like the additional matchday revenue and the commercial benefits. You’ve got to be looking around the £100m mark for a season in the Champions League.

“I don’t think missing one season of the Champions League is a disaster for a club like Liverpool but if you start to miss two or three seasons then it starts to put a real dent in things.”

A big summer ahead then, right?

Absolutely. FSG, Liverpool’s owners since 2010, has made no secret of its attempts to find outside investment and even went as far as considering an outright sale of the club in November.

Crucially, the need for someone to fund a summer rebuild is pressing.

Klopp has admitted that significant changes are required and failure to reach the Champions League on the back of a poor recent run will only have entrenched that belief. Naby Keita, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and James Milner are all out of contract at the end of the season, while Arthur will return to Juventus following the end of his loan spell.

Liverpool had long courted Bellingham as a potential key piece in the jigsaw but hopes of a successful pursuit have receded. Other targets, such as Chelsea’s Mason Mount and Alexis Mac Allister of Brighton & Hove Albion, might be more achievable.

GO DEEPER

No Bellingham, top-four hopes in tatters – FSG must give fans a reason to believe

A clear indication of the funds Klopp will be given is yet to come, but principal owner John W Henry is not about to revise the funding strategy deployed throughout the reign of FSG. “We continue building in a responsible manner,” Henry told the Liverpool Echo last month. “We’ve seen many football clubs go down unsustainable paths.” Investments, he added, would have to be made “wisely”.

Recent history tells us that Liverpool are unlikely to be among the Premier League’s biggest spenders. This season and last both brought net spends of roughly £50million, and the campaign before it was only marginally higher. The season before that — 2019-20, when Liverpool ended their long wait to be champions of England — even saw a profit made in the transfer market.

Unlike Chelsea, who will also miss out on the 2023-24 Champions League (unless they win this season’s competition), it at least ensures financial fair play is not considered a worry.

A failure to back Klopp this summer, though, would make the task of returning to the Champions League for 2024-25 that little bit harder. The ‘Big Six’ is becoming the ‘Big Seven’ with Newcastle United’s transformed wealth but at least there will be the likely prospect of five English clubs featuring in a revised Champions League model from 2024.

Liverpool’s modern period of prosperity has owed much to their success in Europe and it is a revenue stream they can ill-afford to let run dry.

How could Liverpool go about making up the shortfall?

It might be an unpalatable option given the club’s recent glories in the Champions League, but qualification for the Europa League would be the easiest way to plug some gaps.

Not only would matchday revenues be protected with the guarantee of additional home games, but there is also money to be made from the competition where Liverpool finished as runners-up in 2015-16.

Last season’s winners, Eintracht Frankfurt, made €38million from going all the way, while progress to the semi-final stage also earned West Ham United €32million. Liverpool’s strong club co-efficient ranking, with only Bayern Munich, Manchester City and Chelsea higher, would also see them enjoying greater financial benefits given the structure of earnings.

Having to make do with the third-tier Europa Conference League, however, would bring the promise of far less income. Last season’s inaugural winners Roma, who beat Feyenoord in the final, earned €19million.

A fifth-place finish in the Premier League would guarantee qualification to the Europa League group stage next season, with sixth also likely to secure a spot depending on who wins the FA Cup. Unless Sheffield United win the FA Cup, or Brighton win it and finish outside the European places, seventh place would also mean busy Thursday nights next season, but in that instance, it would be in the Europa Conference League. Liverpool are eighth, three points behind Aston Villa in sixth and two behind Brighton in seventh.

“You can claw some of it back (via the other European competitions) but it’s nowhere near the Champions League level,” says Plumley. “You’re looking at something like half the value of the Champions League and that would be going all the way.

“You might make anywhere between £20m and £40m from the Europa League but it’s not at the level of the Champions League. That’s where they want to be.”

Liverpool do have other insulation if next season brings no European football at all. A redevelopment of the Anfield Road stand will boost the capacity of Anfield to 61,000, with an additional 7,000 seats creating the opportunity to significantly increase matchday revenues. Building work, which began last year, is set to be concluded in time for the start of next season.

Liverpool also have new and extended commercial deals with their two main sponsors, Standard Chartered Bank and Expedia, beginning in 2023-24.

One other saving to consider is the wages that Liverpool will need to pay out in 2023-24. Although no player will see a pay cut come directly from missing out on the Champions League, the majority of contracts are heavily incentivised.

Bonuses are typically paid on progression in the Champions League and that was a major factor in Liverpool’s wage bill for the 2021-22 season rocketing to £366million, an increase of nearly 17 per cent on the previous 12 months. No Champions League football in 2023-24, therefore, will inevitably see the club’s wage bill fall.

Where does this leave Liverpool?

Not where they want to be. The last six seasons have had bumps in the road but Champions League football has helped Liverpool become one of European football’s financial powerhouses.

Go back to the 2016-17 season (when Klopp guided the club back to the top four after missing out in six of the previous seven years) and Liverpool were lagging behind other elite clubs.

Deloitte’s Money League, a measure of European football’s most powerful, had Liverpool down in ninth place that season but gradual progression in the subsequent years has brought a climb up to third.

Only Manchester City and Real Madrid had greater revenues last season, with more earned by Liverpool than Manchester United, Paris Saint-Germain and Barcelona. By every metric — broadcast, commercial and matchday revenues — Liverpool have grown in the last six years.

This season will bring falls in revenue but nothing like a campaign without Champions League football. That has become the rock from which Liverpool have built, with a top-four finish assuring them of important financial help.

“That’s always our goal at the start of the season,” chief executive Billy Hogan told German newspaper Bild in Oct 2022. “Qualifying is important because of the turnover we can make in the Champions League but the way we run the club is to make sure we’re as sustainable as possible. You can’t automatically count on Champions League qualification.”

Hogan makes a point but Liverpool, even unwittingly, have grown used to Champions League football.

(Top photo: MB Media/Getty Images)