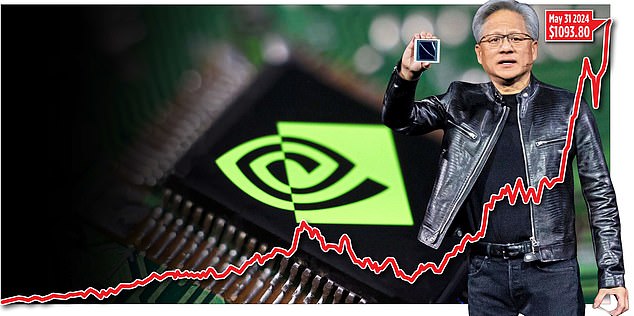

Inside Nvidia, the tech titan whose shares have soared 3,000% in five years. So can it still make YOU money?

It is the stock market success story of the century – and one that will shape the rest of our lives. Since going public on the eve of the Millennium, computer chip designer Nvidia has come from nowhere to the cusp of becoming the world’s biggest company.

In February, Nvidia became the fastest company ever to go from a $1 trillion to a $2 trillion stock market valuation.

Astonishingly, it took just eight months.

Jensen Huang, in his trademark leather jacket, displays the new Blackwell chips, which will cost more than $30,000 each

The company – whose chips have turbo-charged the meteoric rise of artificial intelligence (AI) – is now worth more than the entire FTSE 100 after its share price rose from $34 in June 2019 to $1,090 today. That’s a remarkable 3,000 per cent increase in five years.

With a market value of £2.2 trillion, it is within a whisker of overtaking Apple as the second most valuable enterprise on the planet behind tech giant Microsoft, itself worth £2.5 trillion.

So just how did a start-up without a business plan that was founded in a California diner conquer all before it? And can British private investors get a slice of the action?

Nvidia is the brainchild of Jensen Huang – a Taiwan-born electrical engineering graduate whose parents sent him to the US as a child – and two microchip designers, Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem.

They founded Nvidia in 1993 at a Denny’s restaurant in San Jose in the heart of Silicon Valley.

The plan was to call their company NVision – until they found out that name was taken by a toilet paper manufacturer. Huang – who once worked as a waiter and dishwasher in a Denny’s outlet earning $2.65 a hour – suggested Nvidia instead, based on the Latin word invidia meaning ‘envy’.

Nvidia is the brainchild of Jensen Huang – a Taiwan-born electrical engineering graduate – and two microchip designers, Chris Malachowsky, pictured, and Curtis Priem

He has run the company ever since – becoming one of the world’s richest people in the process.

Nvidia’s main product is a graphics-processing unit (GPU), a wafer-thin circuit board with a powerful microchip at its core. These processors allow lightweight, energy efficient personal computers and laptops to perform a huge number of calculations at high speed.

For decades the big microchip maker was Intel. Nvidia differs from its rival in some key ways.

Intel and others make industry-standard general purpose chips known as ‘central processing units’ (CPU), which handle all the main functions of a computer, producing one mathematical calculation at a time.

But Nvidia’s GPU can complete complex and repetitive tasks much faster, breaking them down into smaller components before processing them in parallel.

If CPUs are delivery vehicles dropping off one package at a time, Nvidia’s GPUs are more like a fleet of high-speed motorbikes spreading across a city. That made them the perfect processors to power the dawning AI revolution.

Nvidia is now worth more than the entire FTSE 100 after its share price rose from $34 in June 2019 to $1,090 today

Unlike Intel, Nvidia doesn’t make its own chips – that’s mainly contracted out to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Crucially, Nvidia not only designs the hardware – the chips – but also the software on which they run.

‘What Nvidia does for a living is not build the chip – we build the entire supercomputer, from the chip to the system, to the interconnects, the NVLinks, the networking, but very importantly the software,’ says Huang, 61.

This secret sauce software package is called Cuda. Nvidia’s chips originally set out to improve the computer graphics used by video gamers. Cuda’s creation in 2006 allowed other, all-purpose applications to run on Nvidia’s chips too.

Initially, AI wasn’t one of them. In the early 2010s, AI was still a technology backwater where progress in areas such as speech and image recognition was slow.

Even less fashionable were ‘neural networks’ – computing structures which mimic the workings of the human brain.

Nvidia’s breakthrough came when the Cuda platform was championed by British-Canadian computer scientist and cognitive psychologist Geoffrey Hinton, dubbed the ‘godfather of AI’.

Two of his students trained a neural network to identify videos of cats using just two of Nvidia’s boards. Google boffins needed 16,000 CPUs to perform the feat. Machine learning had arrived.

The stunning results prompted Huang to go all-in on AI in 2013.

Nvidia’s GPUs were soon to be found in everything from smart cars to robotics and data centres with customers ranging from Tesla to Microsoft and Amazon. One setback was a failed £31 billion bid to buy Cambridge-based chip designer Arm Holdings.

But Nvidia really came of age a year ago with news that ChatGPT – Open AI’s chatbot – was powered by its supercomputers. This propelled the shares into orbit.

The news led to a frenzy among big tech companies and AI start-ups for Nvidia’s processors, leading to shortages that could last into next year.

On May 23 bumper results that beat market expectations caused the company’s value to increase by $200 billion in just one day.

To meet the insatiable demand, Nvidia plans to launch a new generation of AI chips – code-named Blackwell – later this year, costing more than $30,000 each.sni

It can charge so much because of its stranglehold on the AI chip market, with a market share of more than 80 per cent.

This near-monopoly has turned Nvidia into a massive money-making machine, fuelling potentially huge future share price rises.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.