America’s 45th president has excellent taste in Bible translations. When deciding which one to endorse this Easter, Donald Trump chose the King James version, widely considered to be one of the greatest works of English literature of the 17th century. Or rather, he chose a modern repackaging of it dubbed the “God Bless the USA Bible”. This includes in one volume the American constitution, the lyrics of a country song called “God Bless the USA” and the scriptures.

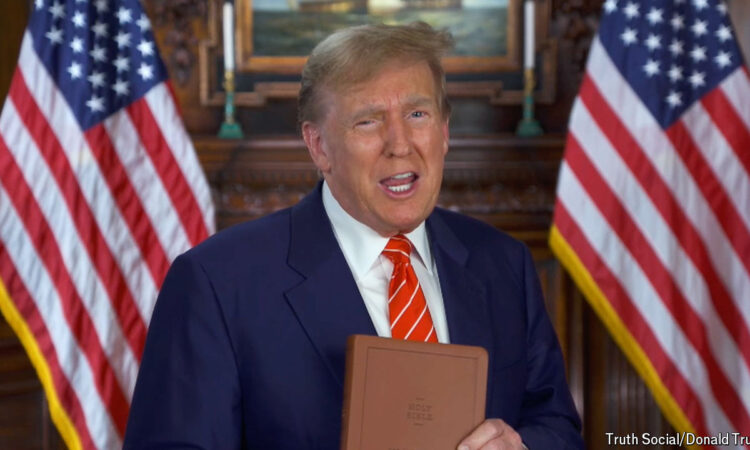

“All Americans need the Bible in their home, and I have many. It’s my favourite book,” intoned Mr Trump in a promotional video. “Religion is so important,” he added. “We must make America pray again.”

And, tacitly, pay again: the new book costs $59.99 (plus postage). Mr Trump is not selling it directly, but receives royalties with each purchase, according to the New York Times. Thus, he has entered the highly competitive business of trying to make a buck from the holy book.

This is a new kind of venture for Mr Trump, whose previous offerings have tended to be flashier: gold-finished Trump sneakers for $399, an enticing Trump cologne for $99. The Bible, far from being a luxury object, inveighs against wealth. It tells of the life of a man who said things like “Blessed are the poor” and “Love your enemies”. Such sentiments are not easily mistaken for those of Mr Trump, which include “Part of the beauty of me is that I am very rich” and “The worst thing a man can do is go bald.”

The market in religious publishing is thriving in America: the recent StatShot Annual Report from the Association of American Publishers found that revenues of religious presses had risen 7% in the first ten months of 2023, to $674m. A slice of that might defray at least some of Mr Trump’s legal expenses, but this is a very unusual market, with obstacles for new entrants.

The biggest is that many suppliers insist on giving its most popular product away for free. The Gideons, a Christian charity founded in 1899, has placed 2.5bn Bibles and New Testaments in hotels, hospitals, prisons and domestic-violence shelters around the world—roughly one for every Christian man, woman and child. Weary travellers yearning for gospel truths can simply reach into a bedside drawer and find some. Other groups have posted the entire Bible online, so the faithful can search for their favourite verses. Against such unfair, cut-price competition, can Mr Trump compete?

Probably, for several reasons. First, the revered text he is touting is not subject to copyright—a concept that did not exist when the King James Bible was first published in 1611. So he is demanding a high price for a text whose long-dead authors do not need paying. Never mind scribbling notes in the margins of the books of the minor prophets; the profit margins on each copy of this book should be major.

None of that will matter if no one buys the God Bless the USA Bible. But it has two celebrity endorsements: Lee Greenwood, the country star who sings “God Bless the USA”, is involved, too. And Mr Trump is pushing the tome during a bitter election campaign, to a vast number of followers, many of whom are passionate both about scripture and about supporting the former president against his fiendish enemies.

Others in the devotional publishing industry have faced the same challenge as Mr Trump—how to refresh a blockbuster written thousands of years ago—and come up with even more creative solutions. They cannot commission sequels by living authors, as the literary estates of Agatha Christie and Ian Fleming have done to produce new Hercule Poirot and James Bond stories. But they can commission new translations (a huge task) or tailor versions for specific audiences.

Thus, from Zondervan, the Christian arm of HarperCollins, you can buy the “Boys Bible” (“Gross and gory stuff you never knew was in the Bible”). From a smaller German outfit, there is the “Biker Bible” (“the whole New Testament and life stories of bikers”). The Bible is long and confusing: many modern readers yearn for shortcuts to passages that might be especially relevant, and commentaries to aid comprehension. Others seek whimsy: you can buy the “Mother’s Bible” (it’s pink), or Bibles in regional dialects (a Glaswegian one opens with “In the Beginnin’”). There are even scriptures in fictitious tongues such as Klingon, from “Star Trek”, or Quenya, invented by J.R.R. Tolkien.

Such experimentation is much easier with the Bible than it is with the Koran, and much easier today than in previous centuries. In the 16th century the scholar William Tyndale translated the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into English in a way that displeased the church. He was later burned at the stake for heresy. The church was less tolerant of novelty in those days, and created literal ghostwriters.

Since many people take the Bible literally, careful proofreading is essential. In 1631 printers in London accidentally left the word “not” out of the seventh commandment, thus rendering it as “Thou shalt commit adultery.” This delighted many readers, but not the authorities. The printers were hit with ruinous fines and lost their licence. The “Wicked Bible” subsequently became a collector’s item; surviving copies are now valued at tens of thousands of dollars. Whether future generations will treasure Mr Trump’s Bible so dearly remains to be seen. ■