Germany wants to end Europe’s semiconductor dependence on Asia. Is it up to the challenge?

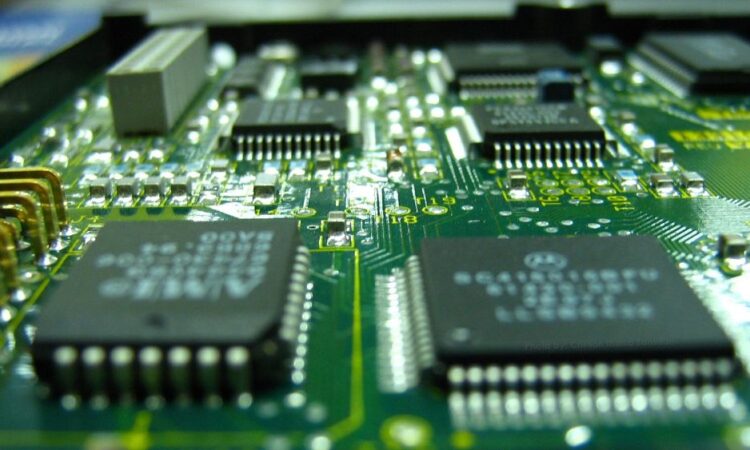

From use in electric cars and smartphones to wind turbines and even missiles, electronic chips – or semiconductors – are the “oil of the 21st century,” components on which “everything else depends”.

These were the words of Germany’s chancellor Olaf Scholz at the inauguration of a new factory built by the German semiconductor manufacturer Infineon earlier this month.

On a trip to Seoul last weekend, he again spoke to his Korean counterparts about semiconductors, calling on South Korea to invest in Europe to strengthen supply chains.

The European Union’s stated objective is to reach 20 per cent of the world market by 2030, twice as much as its share today. In order to hit this target, it will require a fourfold increase in production on the Old Continent.

This is the aim of the European “Chips Act,” which was concluded by EU lawmakers in April, which plans to mobilise €43 billion in public and private investment.

As Europe’s largest economy, Germany is spearheading this movement to reduce dependence on Asia.

In addition to Infineon’s new factory in Dresden – a €5 billion project – the American groups Intel and Wolfspeed have announced major investments in Germany in recent months.

It would be a major win for Germany if it were to win the first European factory of the Taiwanese group TSMC – one of the world’s largest chip manufacturers.

Discussions have been underway for more than a year for a plant in the Dresden region, Europe’s leading microelectronics hub, already dubbed “Silicon Saxony”. A decision is expected in August at the earliest, according to TSMC.

An unachievable goal?

But some 200 km away in the Magdeburg region, the euphoria generated last year by the announcement of a €17 billion investment by the American giant Intel has given way to doubts.

The construction of the factory, which was to begin in the first half of 2023, has not started.

“Many things have changed” in a year, admitted the group in a statement to AFP, which suffered a record loss in the first quarter of the year due to a sharp decline in sales of personal computers and smartphones.

In addition to “geopolitical challenges,” “disruptions in the global economy have led to increased costs, from building materials to energy,” the group said.

Additional public aid is envisaged to “fill the cost gap of the planned project, which has increased significantly,” the German Ministry of Economy acknowledged.

‘No self-sufficiency’

This race for subsidies is not sitting well with a lot of Germans.

“We are spending a lot of money… to increase the security of supply a little,” worries Clemens Fuest, one of the country’s most respected economists.

While public aid to Dresden and Magdeburg will run into billions, Germany and Europe will remain largely dependent on chips produced outside the continent, and “you have to imagine what could have been done with that money,” explained Mr Fuest, president of the IFO economic institute, in an interview with German broadcaster ARD.

If dependencies can be reduced, there will be “no self-sufficiency for any country or region” in semiconductors, Infineon CEO Jochen Hanebeck also warned this month.

On the contrary, some professionals believe that aid should be even more massive.

“The funds announced under the Chips Act are a good start, but they are still insufficient by world standards,” Frank Boesenberg, director of Silicon Saxony, the organisation promoting semiconductors in the Dresden region, told AFP.

Taiwan (where 90 per cent of the world’s most advanced chips are produced), South Korea, and increasingly China, currently dominate the market.

Europe also faces competition from the US, which is spending considerable sums to promote domestic production.

Another major challenge for Germany will be to find enough workers.

According to a study carried out in December by the German Economic Institute, there is currently a shortage of 62,000 skilled workers in various professions in the chip industry.