Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2020.

Building on the literature on trust in institutions, the article looks at the state, evolution and sociodemographic breakdown of citizens’ trust in the ECB and support for the euro. Drawing on a novel typology of attitudes towards Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and using microdata from Eurobarometer surveys since the introduction of the single currency, the analysis tracks the prevalence of supporters and sceptics of EMU over time and across euro area countries. It further explores the sociodemographic characteristics, economic perceptions and, more broadly, European sentiments within these groups. In this way, it provides insights into the factors shaping citizens’ attitudes towards the ECB, the euro and EMU, and helps identify possible avenues for enhancing trust. The analysis indicates that popular support for EMU – in particular, trust in the ECB – hinges to a large extent on citizens’ perceptions of their personal situation and the overall economic context, as well as their broader attitudes towards the European Union, while other sociodemographic indicators seem to be less relevant.

1 Introduction

The financial and sovereign debt crisis brought issues of economic and monetary integration to the forefront of European and national political debates. This article explores the impact of these developments on public opinion. To this end, it traces developments in citizens’ attitudes towards European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) along two central dimensions: citizens’ support for the euro as the most tangible outcome of economic and monetary integration at the European level; and citizens’ trust in the European Central Bank (ECB) as the institution tasked with defining and implementing monetary policy for the euro area and safeguarding the stability of the single European currency.

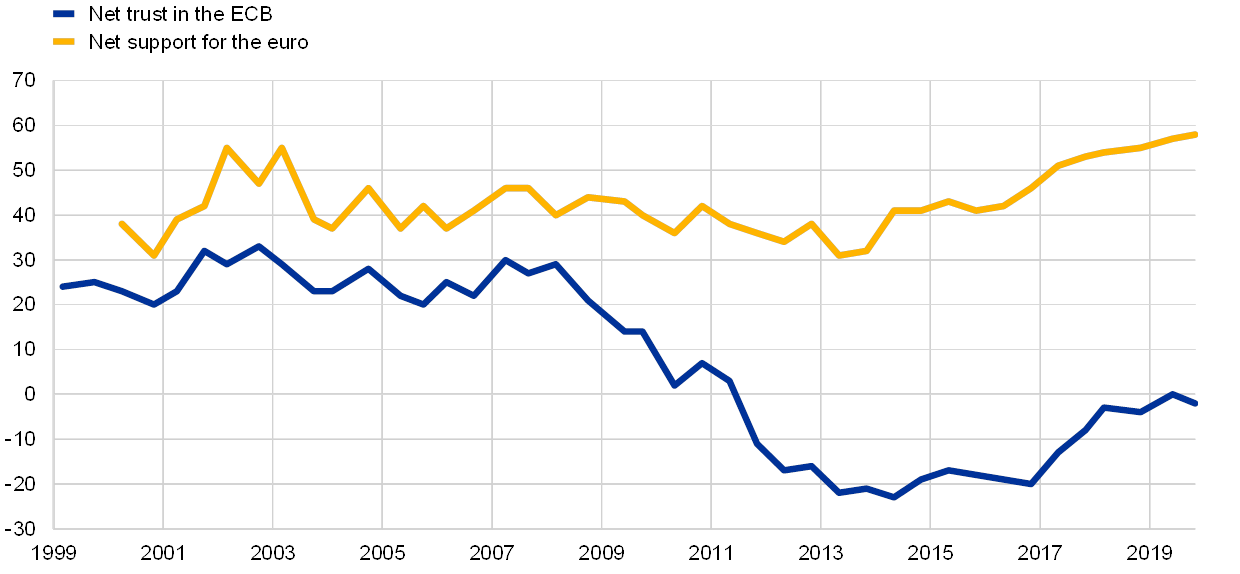

While the euro and the ECB are closely linked at the institutional level, public opinion towards the two has followed divergent trends since the crisis. Citizens’ support for the euro remained stable at high levels even at the height of the crisis. By contrast, public trust in the ECB declined significantly during the crisis and has since been slow to recover. In autumn 2019 support for the euro among euro area citizens stood at 76%, following an almost continuous increase from spring 2016, while 18% of respondents in the euro area were opposed to the euro. By contrast, a total of 42% of euro area respondents expressed trust in the ECB, compared with 44% who said they did not trust the institution.[1] As a result, net trust in the ECB remains in negative territory, while net support for the euro has been increasing steadily since 2013 and reached a record high in autumn 2019 (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

Net trust in the ECB and net support for the euro

Euro area, spring 1999 – autumn 2019

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: Net support for the euro is calculated as the share answering “for” minus the share answering “against” to the question “Please tell me whether you are for or against it: A European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro.” Net trust is calculated as the share of respondents giving the answer “Tend to trust” minus the share giving the answer “Tend not to trust” to the question “Please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?: The European Central Bank.” Respondents who answered “don’t know” are excluded in both cases.

This article explores this divergence in citizens’ support for the euro and trust in the ECB in greater detail. Who are the citizens who support the common currency, but do not have confidence in the ECB? How do they differ from those citizens who support the euro and have trust in the ECB? To explore these questions, we introduce a fourfold typology of attitudes towards EMU based on different combinations of citizens’ views on the euro and the ECB. Drawing on survey data from the Eurobarometer, we analyse the prevalence of the different groups in the general public of the euro area from the inception of the common currency in 1999 to 2019.[2] We explore variation at euro area EU Member State and regional levels, among different sociodemographic groups and based on citizens’ economic perceptions and socio-political orientations.

2 The relevance of public trust in the ECB and support for the euro

Public trust matters for central banks. Central banks rely on steering inflation expectations to fulfil their mandate. This requires a basic understanding of economic and financial matters, and a high level of trust among the public. A high level of trust in the central bank’s ability to fulfil its mandate facilitates its task of anchoring inflation expectations, increasing the effectiveness of the central bank’s monetary policy measures. Conversely, a lack of public trust makes the central bank more vulnerable to political pressure, as politicians have greater incentive to make critical comments and could undermine its independence.[3]

Trust in the ECB is correlated with citizens’ understanding of its mandate and affects the formation of household inflation expectations. There is evidence that individuals’ inflation expectations are related to their knowledge of the ECB’s policy objective and their knowledge of how the ECB provides information about its monetary policymaking process.[4] Research also suggests that trust in the ECB affects the formation of household inflation expectations,[5] including when controlling for respondents’ knowledge of the ECB’s objectives and their level of financial literacy.[6]

Citizens’ support provides legitimacy to the project of EMU. Citizens’ support provides the necessary legitimacy for supranational governance in an area that is traditionally a core competence of the nation state, namely to conduct its own monetary policy. It is important that the public understands and accepts the ECB’s policies in order to reinforce its strong political independence. Moreover, while the sustainability of a currency is mostly taken for granted in the national context, it has been argued that, as a union of sovereign states, EMU must ultimately rely on a “sense of common purpose”[7] that provides a political bond among members of the monetary union beyond standard economic arguments.[8] These political bonds were even more important during the global financial crisis that started in 2008, when membership in the euro area was framed as creating winners and losers, and questions regarding the desirability of European economic integration became salient in national political debates and election campaigns.[9]

3 A puzzle with four pieces: a typology of attitudes towards EMU

Support for the euro can be conceptualised as a reflection of both satisfaction with the concrete output of the currency and support for the value of economic integration. Citizens’ perceptions of the euro are likely to represent both their concrete experiences with the currency in day-to-day life and a more diffuse support of the idea of a currency union and the value of economic and monetary integration that underpins the EMU regime. In effect, the euro is considered one of the most visible embodiments of the EU,[10] and citizens’ support for the value of European integration is positively related to support for the euro.[11]

Trust in the ECB represents a form of institutional trust, reflecting a positive perception of the central bank and its specific policies. The most concrete output and obvious yardstick for assessing the ECB’s performance is the inflation rate as a measure of price stability, which is the ECB’s primary objective pursuant to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). However, in the course of the global financial crisis, the ECB was characterised in the mass media as one of the key actors in charge of addressing the economic crisis.[12] Indeed, during the crisis, citizens became more aware of the ECB and more inclined to state an opinion on whether they trusted it .[13] At the same time, since it is an EU institution, citizens are likely to evaluate the ECB as part of the overall EU framework, together with other institutions, such as the European Commission or the European Parliament. Thus, when asked whether they trust the ECB, citizens may not only take into account inflation developments, but also other macroeconomic developments and their overall perception of the EU.

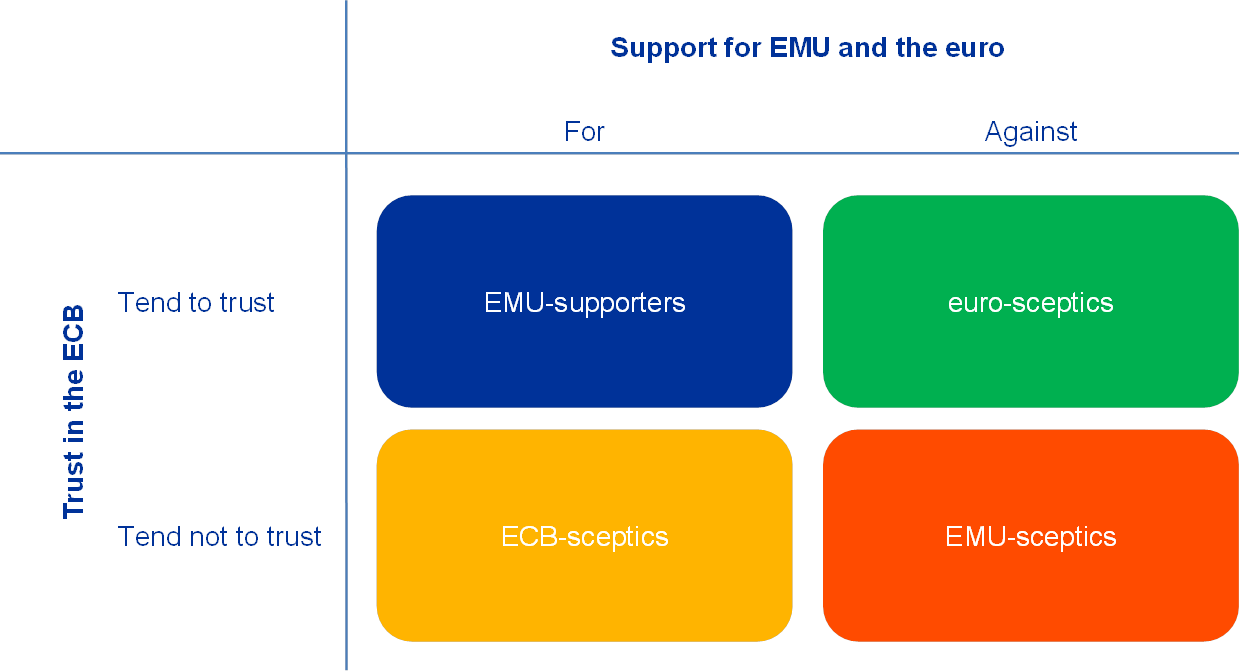

Taken together, citizens’ views on the euro on the one hand and the ECB on the other shed light on their attitudes towards EMU. Citizens can hold consistently positive or negative views on both the euro and the ECB, but they can also diverge in their views on the single currency and the central bank. Figure 1 shows a cross-tabulation of support for the euro and trust in the ECB, which results in four groups of supporters and sceptics of EMU: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters).[14]

Figure 1

Typology of attitudes towards EMU

Note: The fifth group, which includes respondents who answered “don’t know” to one or both of the questions, is not included in the overview.

Different combinations of attitudes towards EMU hold different implications for economic and monetary integration. Among these four groups, the first group, referred to as “EMU-sceptics,” appears to be the most critical to understand in that these citizens, lacking support for either the euro or the ECB, may be open to or actively support a reversal of economic and monetary integration, potentially undermining the smooth functioning of EMU. A significant prevalence of the second group, namely “ECB-sceptics” among euro area citizens may reduce acceptance of ECB actions; at the same time, the continued support in this group for the single currency indicates an outlook that is in principle pro-European. The third group, “euro-sceptics” is puzzling in that these citizens trust the ECB, but oppose a single currency; this may be explained by general scepticism towards policymaking at the EU level or attachment to national currencies that were superseded by the euro, coupled with high levels of trust in the functioning of institutions. The fourth group, “EMU-supporters,” provide the strongest support for the project of economic and monetary integration in that they favour the single currency and express trust in the ECB.

4 What we know about the different groups in the typology of attitudes to EMU

4.1 Measuring trust in the ECB and support for the euro

The empirical analysis of the prevalence of the different groups of supporters of EMU draws on survey data from the Eurobarometer. We use individual survey data from 40 waves of the bi-annual Standard Eurobarometer from 1999[15] to 2019. The analysis is restricted to respondents from Member States in the euro area. As a (repeated) cross-sectional survey, the Eurobarometer does not allow for panel analysis and cannot track intra-individual changes in attitudes over time. Nevertheless, it gives an insight into attitudes towards the euro and the ECB among euro area citizens over time and under changing political and macroeconomic conditions. While the Eurobarometer has been criticised for a number of methodological reasons, it remains one of the most widely used cross-national surveys and has become the main data source for comparative empirical research on public opinion in the EU and on the politics and sociology of European unification.

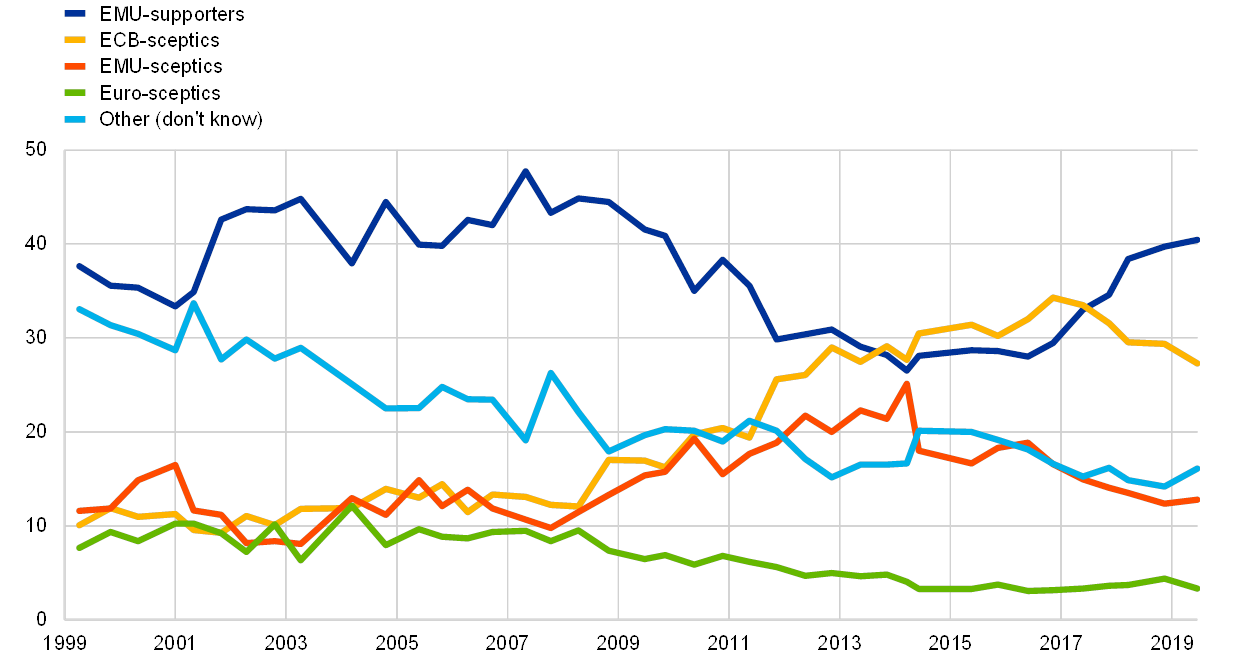

Support for the euro and trust in the ECB are operationalised using standard measures in the literature. To assess respondents’ support for the single currency, we use the question “What is your opinion on each of the following statements? Please tell me for each statement, whether you are for it or against it: A European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro.” To assess respondents’ support for the ECB, we use the question “Please tell me if you tend to trust or tend not to trust these European institutions: The European Central Bank.” Respondents replying “don’t know” to one or both of the questions are placed in a fifth group called “Other (don’t know)”, while those refusing to answer are omitted from the analysis.[16] Depending on the survey wave, between 20-35% of respondents fall into this fifth category (see Chart 2) and, of these, roughly two-thirds reply “don’t know” to the question regarding trust in the ECB.

The design of the Eurobarometer questionnaire may affect response behaviour for the items regarding support for the euro and trust in the ECB. In particular, the indicator of trust in the ECB is part of a series of questions assessing respondents’ trust in different EU institutions, notably the European Commission and the European Parliament. This design may invite satisficing behaviour, whereby respondents do not sufficiently differentiate between items within the series because they lack distinct views on the individual institutions and/or may try to be consistent in their response behaviour, supporting or rejecting all statements in the series.[17] Furthermore, the order of the questions in the questionnaire may affect response behaviour, as questions asked earlier in the survey may affect response behaviour on later questions.

A comparison of findings from the Eurobarometer and other datasets lends external validity to the results. While we cannot exclude that questionnaire effects have an impact on the findings, a cross-validation of levels of trust in the ECB and support for the euro as measured by the Eurobarometer with evidence on citizens’ attitudes towards the single currency and the ECB from other EU-wide and national datasets shows that findings are broadly comparable across datasets. For example, the Autumn 2019 Standard Eurobarometer[18] (fieldwork conducted in November 2019) found that 76% of respondents in the euro area were in favour of the single currency. In a Flash Eurobarometer[19] from roughly the same period (fieldwork conducted in October 2019), 65% of respondents indicated that the euro was a good thing for their country and 76% thought it was a good thing for the EU. Both Standard and Flash Eurobarometer surveys have observed an upward trend in support for the euro since 2016. National surveys that occasionally field questions on trust in the ECB show similar levels of trust as those found based on Eurobarometer data.[20]

The subsequent sections assess support for EMU by means of univariate analysis. The changes in the make-up of the different groups in the typology are illustrated along different sociodemographic indicators. Aggregated data for the euro area are weighted to account for differences in population size between euro area countries applying the standard post-stratification weights provided for in the Eurobarometer survey data. This analysis can gauge simple correlations between the type of support for EMU and the individual sociodemographic indicators in question, and, through its time dimension, identify turning points and possible triggers of changes in support for EMU. However, the analysis neither controls for confounding variables, nor provides quantitative estimates of the strength of observed correlations, and it is also not able to establish causality.[21]

4.2 Support for EMU since the global financial crisis

In the euro area aggregate, EMU-supporters are the largest group, having recovered from the trough reached during the global financial crisis. Chart 2 shows the share of respondents in each of the four groups from 1999[22] to 2019 for the euro area aggregate. Prior to the crisis, a relative majority of around 40% of euro area citizens were EMU-supporters (dark blue line in Chart 2). This group shrank from the onset of the financial and economic crisis in 2008-09 and reached a trough in 2013-14. It stabilised in subsequent years and in 2017-18 recovered to levels just below those seen before the crisis. In the aftermath of the crisis, citizens appeared to have lost confidence in the ECB, but did not necessarily turn against the project of a single currency per se, as evidenced by the growing number of those still supporting the euro, but lacking trust in the ECB. This group became the largest group in the years 2013-16 (yellow line in Chart 2).There was also an increase in the number of EMU-sceptics (red line in Chart 2), which peaked in 2014, when close to 25% of euro area citizens supported neither the euro nor the ECB. By spring 2018 this group had contracted, representing less than 15% of respondents. The fourth group, i.e. citizens who support the ECB but not the euro (green line in Chart 2), has decreased further from low levels to become negligibly small across the euro area in recent years (less than 5% of respondents). Finally, the decreasing number of respondents who reply “don’t know” to one or both of the questions (light blue line in Chart 2) indicates that growing awareness of and familiarity with the single currency and the ECB – be it through day-to-day experience with the euro as a means of payment or increased media attention on the ECB in the crisis – has also led citizens to be more confident in expressing an opinion about the two.

Chart 2

Typology of attitudes towards EMU over time

Euro area, spring 1999 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (Other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions.

The developments in support for and scepticism about EMU at the euro area level, as measured by the Eurobarometer, shows that trust in the ECB is more volatile than support for the euro. The relative decline in the size of the group of EMU-supporters over the period 2008-13 is mainly due to the concurrent decrease in trust in the ECB, as indicated by the growing number of ECB-sceptics over the same period (see Chart 2). These findings suggest that support for the euro is more resistant to negative experiences such as the crisis, while the decline in trust in the ECB during the economic downturn indicates a more performance-related orientation, in line with recent findings by other studies.[23] At the same time, the growing share of euro area citizens that neither trust the ECB nor support the euro (EMU-sceptics) over the course of the crisis suggests that negative experiences during the crisis also negatively affected support for the EMU project more generally, possibly via dissatisfaction with the outputs of European economic governance. However, this trend seemed to stop and eventually reverse as the economy recovered. Owing to data availability, these trends do not reflect the potential impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic that started in early 2020.

The decline in trust in the ECB is part of a broader decline in trust in public institutions in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. In effect, not only the ECB, but most national and supranational public institutions in Europe saw public trust decrease in the past decade, making the decline in trust in the ECB part of a wider trend. Currently the level of trust in the ECB seems to be at a neutral level, with roughly equal shares of respondents expressing trust or distrust in the ECB. Box 1 summarises developments in public trust in EU and national institutions since the global financial crisis.

Box 1 Developments in trust in public institutions since the global financial crisis

The decline in popular trust in the ECB over the past decade occurred in the context of a broader decline in trust in public institutions. Since the onset of the global financial crisis, there has been a decrease in trust in public institutions in Europe at both national and supranational level. In fact, this trend can be observed across most advanced economies. The decline in trust in the ECB seen over the past decade is thus not specific to the ECB. At the same time, attitude surveys indicate that popular trust in the ECB has declined more than trust in national and even other EU institutions. This box explores the developments in trust in the ECB relative to other institutions, with a view to teasing out common and distinct features of the decrease, as well as recent improvements in popular trust in the ECB.

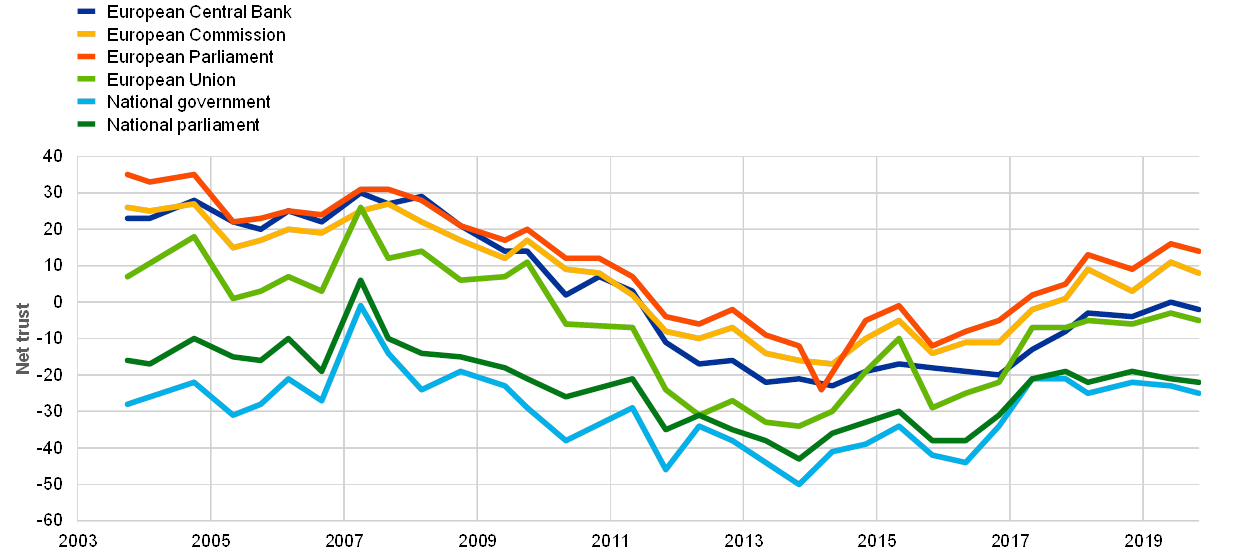

Trust in EU and national institutions

In the decade running up to the global financial crisis, net trust among euro area citizens in the European Commission, the European Parliament and the ECB stood at robustly positive and roughly comparable levels, with the European Parliament enjoying a small lead (see Chart A). Net trust in these EU institutions was significantly higher than net trust in national governments or national parliaments by a margin of between 20 and 40 percentage points. Even before the crisis, net trust in national governments or parliaments already tended to be negative (i.e. with more survey respondents saying they tended not to trust national institutions than those who tended to trust them). With the onset of the crisis, trust in national institutions fell further, but net trust in the abovementioned EU institutions and the EU as a whole also descended into negative territory.

While the fall in trust was initially rather broad-based across public institutions, the loss of trust has been more pronounced for EU institutions, and the recovery in trust among them has been uneven. In fact, compared with both EU and national institutions, trust in the ECB appears to have been disproportionately affected by the crisis, experiencing a deeper fall and a slower recovery. The result is that, currently, net trust in the ECB still lies in slightly negative territory, standing at -2 percentage points in autumn 2019, whereas net trust in the European Commission and the European Parliament has been positive since 2017.

Chart A

Trust in European and national institutions

Euro area, autumn 2003 – autumn 2019

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: Net trust is calculated as the share answering “Tend to trust” minus the share answering “Tend not to trust” in response to the question “Please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?: NAME OF INSTITUTION.” Respondents who answered “don’t know” are excluded in both cases.

Trust in the ECB compared with trust in national institutions

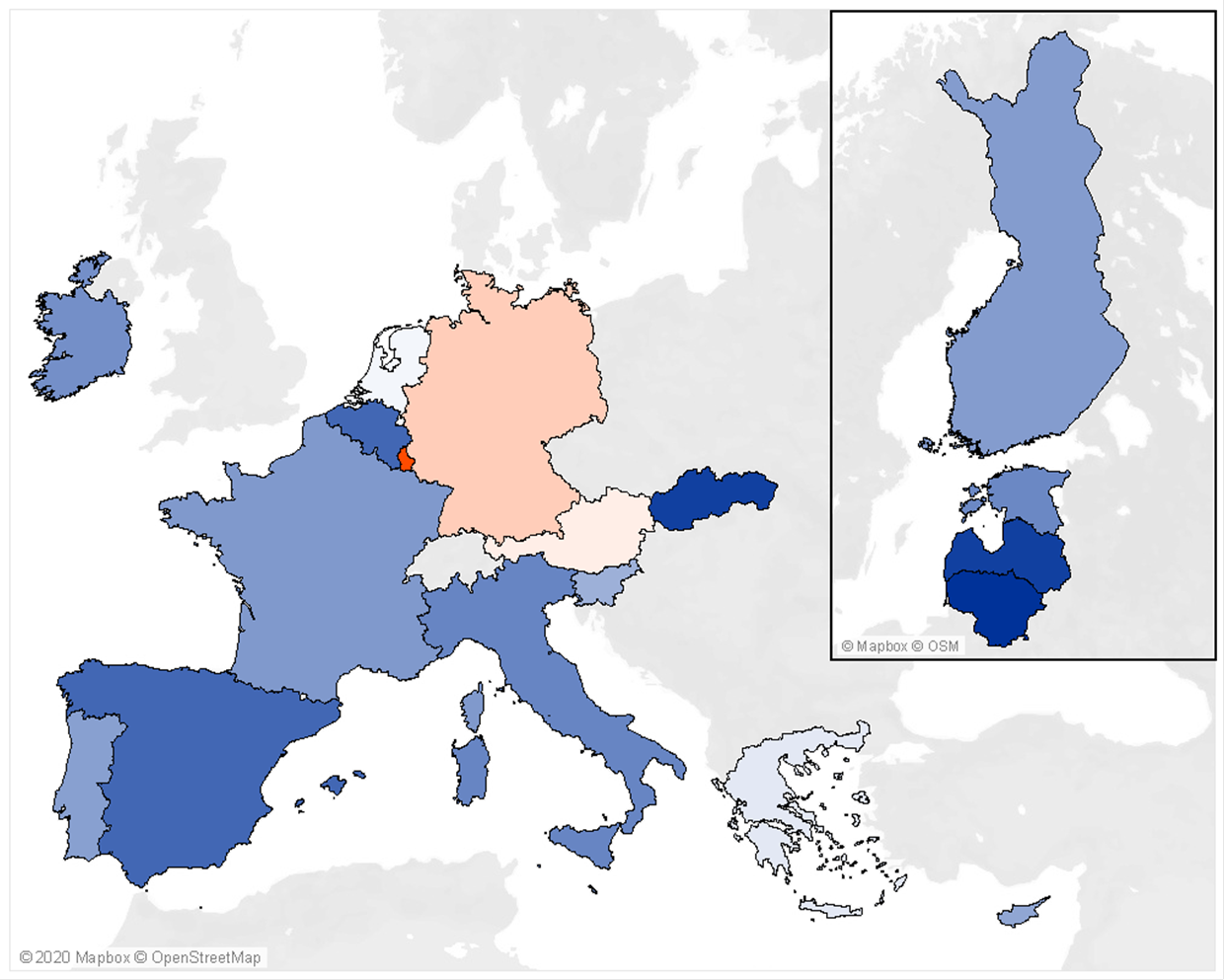

Since reaching a trough in spring 2014, net trust in the ECB has recovered partially, and the gap over national governments has widened again slightly. At the aggregate euro area level, net trust in the ECB in late 2019 was 23 percentage points higher than net trust in the national governments. However, a closer look reveals that the widening gap is masking heterogeneous developments at the country level. Overall, albeit still slightly negative at the aggregate euro area level, at the end of 2019 net trust in the ECB was above the level of net trust in national government in all euro area countries except Austria, Germany and Luxembourg (see Figure A).

Broadly speaking, it appears that the trust gap has fallen more in those countries where the gap was highest prior to the crisis, and that trust in the ECB in comparison to trust in national government suffered particularly in the countries most affected by the crisis and in Germany and the Netherlands. Spain and Cyprus are the main exceptions among the countries hit heavily by the crisis. It corroborates the wider finding of this article that citizens hold the ECB responsible for – or at least associate it with – the general economic situation at both national and European levels, as well as their own personal financial situation, more than they do national governments.

Figure A

Gap between net trust in the ECB and net trust in the national government

Euro area countries, autumn 2019

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: Net trust is calculated as the share answering “Tend to trust” minus the share answering “Tend not to trust” to the question “Please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?: NAME OF INSTITUTION.” Respondents who answered “don’t know” are excluded in both cases. The trust gap varies between -200 and 200, as net trust for each institution varies between -100 and 100.

4.3 Geographic correlates of support for EMU

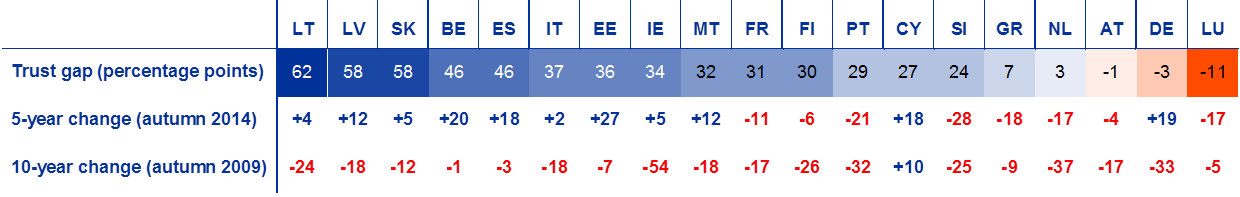

Across Member States in the euro area, support for EMU has improved since the crisis. Looking at the developments in support for EMU by country, euro area countries fall roughly into two groups: those where support for EMU fell during the crisis but has since largely bounced back, and those that have seen robust support for EMU throughout the crisis years (see Chart 3).

Countries severely affected by the economic crisis experienced a dip in support for EMU. It is not surprising that the first pattern is found almost exclusively in countries that were severely affected by the economic crisis after 2008 and 2009, and is particularly strong in Ireland, Greece, Spain, Cyprus, Portugal and Slovenia. With the exception of Slovenia, all of these countries entered financial assistance programmes during the crisis. In these countries, typically the share of ECB-sceptics grew mainly during the crisis. The share of euro-sceptics also experienced a temporary spike, but has since returned to near pre-crisis levels.

Countries less affected by the crisis tend to show relatively stable support for EMU. By contrast, the second pattern of high and relatively stable support for EMU can be observed in countries that were less affected by the crisis, such as Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Malta, Austria, Slovakia and Finland. In these countries, since the crisis the share of ECB-sceptics has typically grown moderately and at a steady pace from a very low level, trending slightly above the share of euro-sceptics. However, both scepticism towards the ECB and the euro remained minority attitudes throughout the crisis and afterwards.

Germany, France and Italy display idiosyncratic patterns of support for EMU. The three largest euro area countries – Germany, France and Italy – are important exceptions to the two patterns described above. They follow a common pattern of their own that is characterised by support for EMU that is also fairly stable but moderate. During the crisis, when there was a slight dip in support for EMU, ECB-sceptics (in the case of France and Germany) and EMU-sceptics (in the case of Italy) temporarily constituted the largest groups. The relative sizes of the groups have since reversed, but the share of ECB-sceptics in these countries has lingered above pre-crisis levels (and in France is on a par with the share of EMU-supporters).

Chart 3

Typology of attitudes towards EMU by country

Euro area countries, spring 1999 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (Other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions.

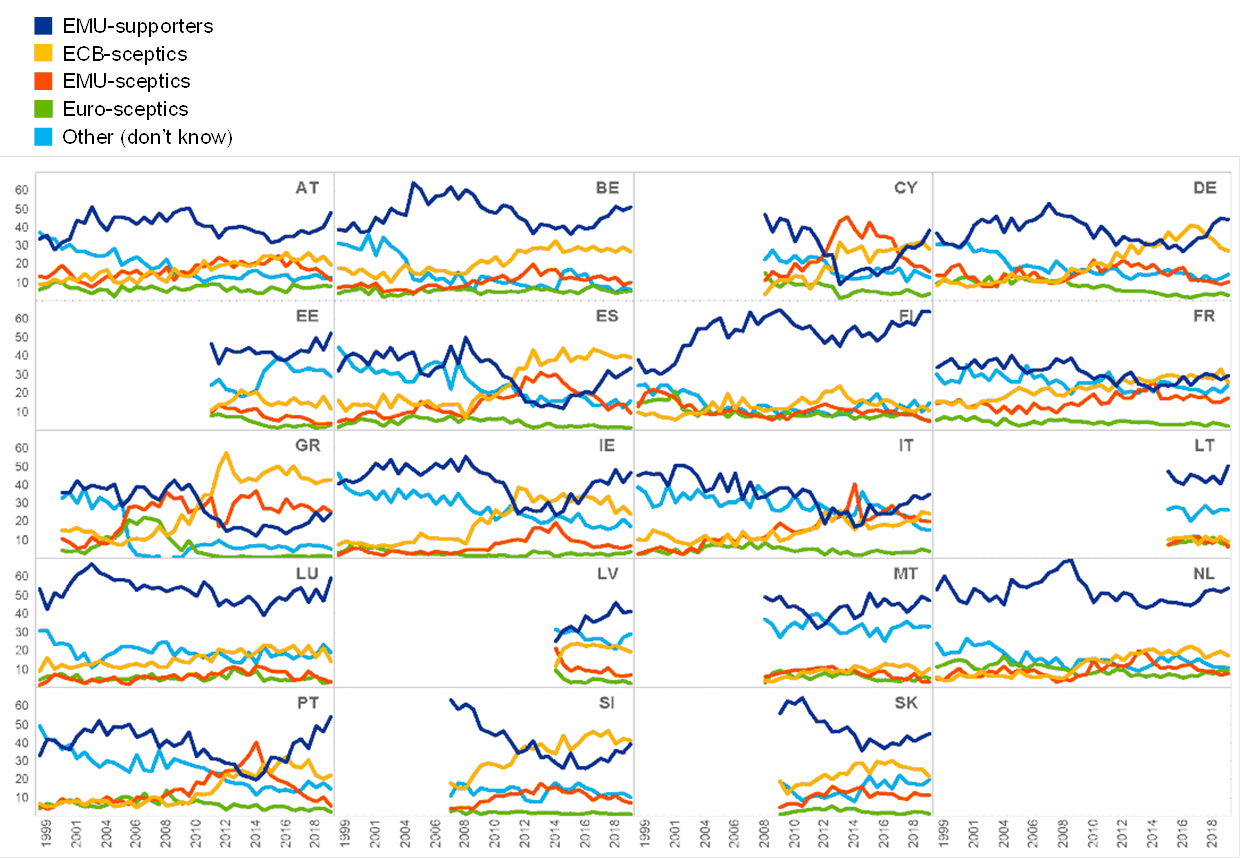

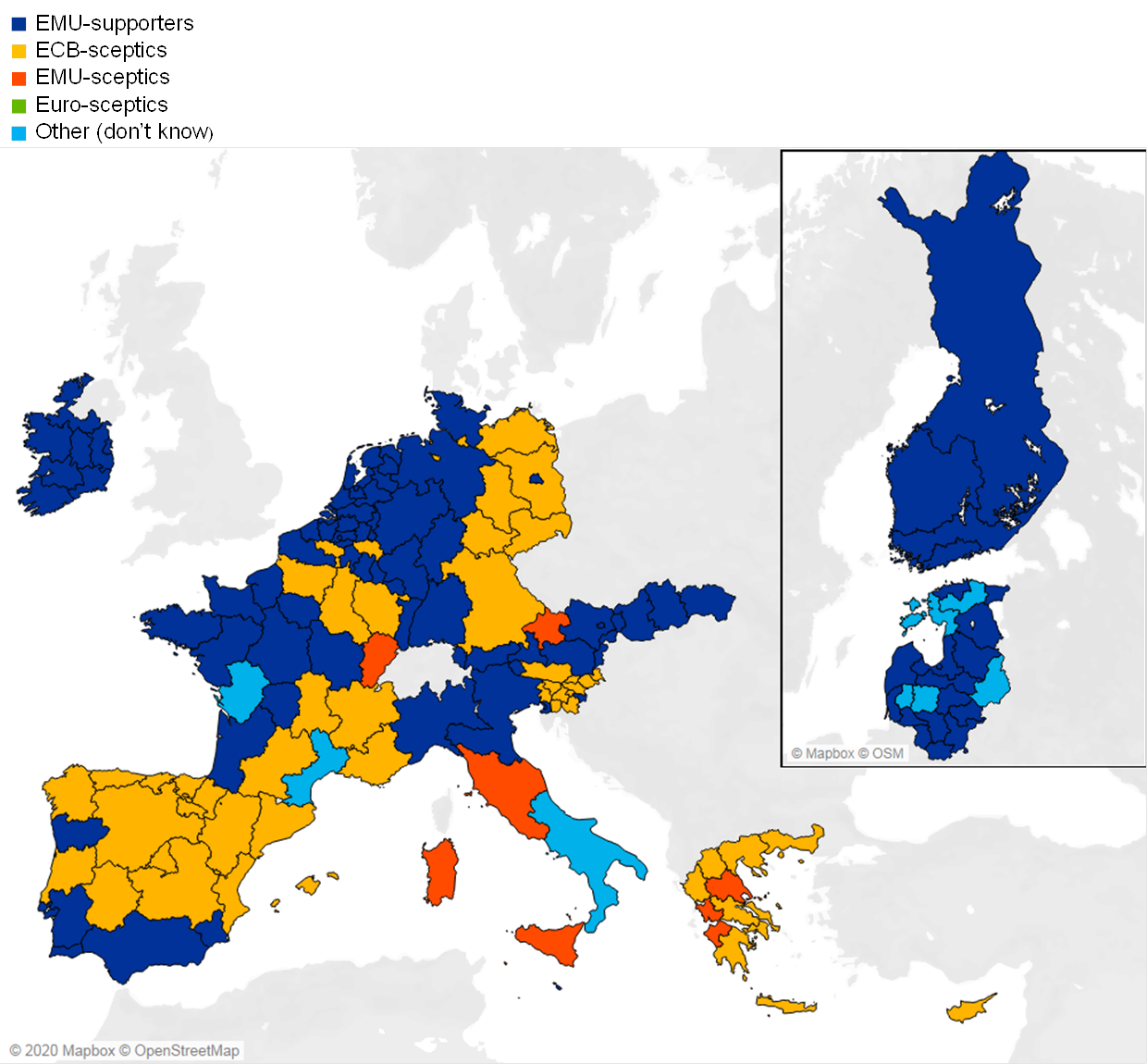

There are also considerable differences in patterns of support for EMU within countries. Applying the typology of attitudes towards EMU at the regional level to identify the predominant group by region[24] reveals that the geography of support for EMU varies significantly by country (see Figure 2).[25] By showing only the predominant group in each region, which in some regions has only a very narrow lead over other groups, the map tends to overstate differences between regions. Nevertheless, it serves to illustrate that in some countries, one group in the typology dominates throughout, while other countries show strong regional differences. Among the countries with strikingly homogenous regional attitudes are Ireland, the Netherlands, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Finland, where EMU-supporters are the predominant group throughout the country. Slovenia is similarly homogeneous, but is predominantly ECB-sceptic.

Countries with heterogeneous patterns of support for EMU at the sub-national level tend to see two predominant groups. In the cases of Belgium, Germany, Spain, France and Portugal, there is a fairly even split between regions where EMU-supporters are in the majority and regions where ECB-sceptics are in the majority. Regions in Italy either have a majority of EMU-supporters or EMU-sceptics, and regions in Greece are either predominantly EMU-sceptic or ECB-sceptic. Austria falls somewhere in-between these patterns, being relatively homogeneous with EMU-supporters constituting the majority in most regions, but with one region predominantly EMU-sceptic and one predominantly ECB-sceptic.

Figure 2

Map of typology of attitudes towards EMU

Euro area NUTS regions, autumn 2016 – spring 2019

(group with the largest share of respondents in each NUTS region)

Source: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro- sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions. The NUTS classification varies between NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 across Member States and depends on the granularity coded in the Eurobarometer survey.

4.4 Sociodemographic correlates of support for EMU

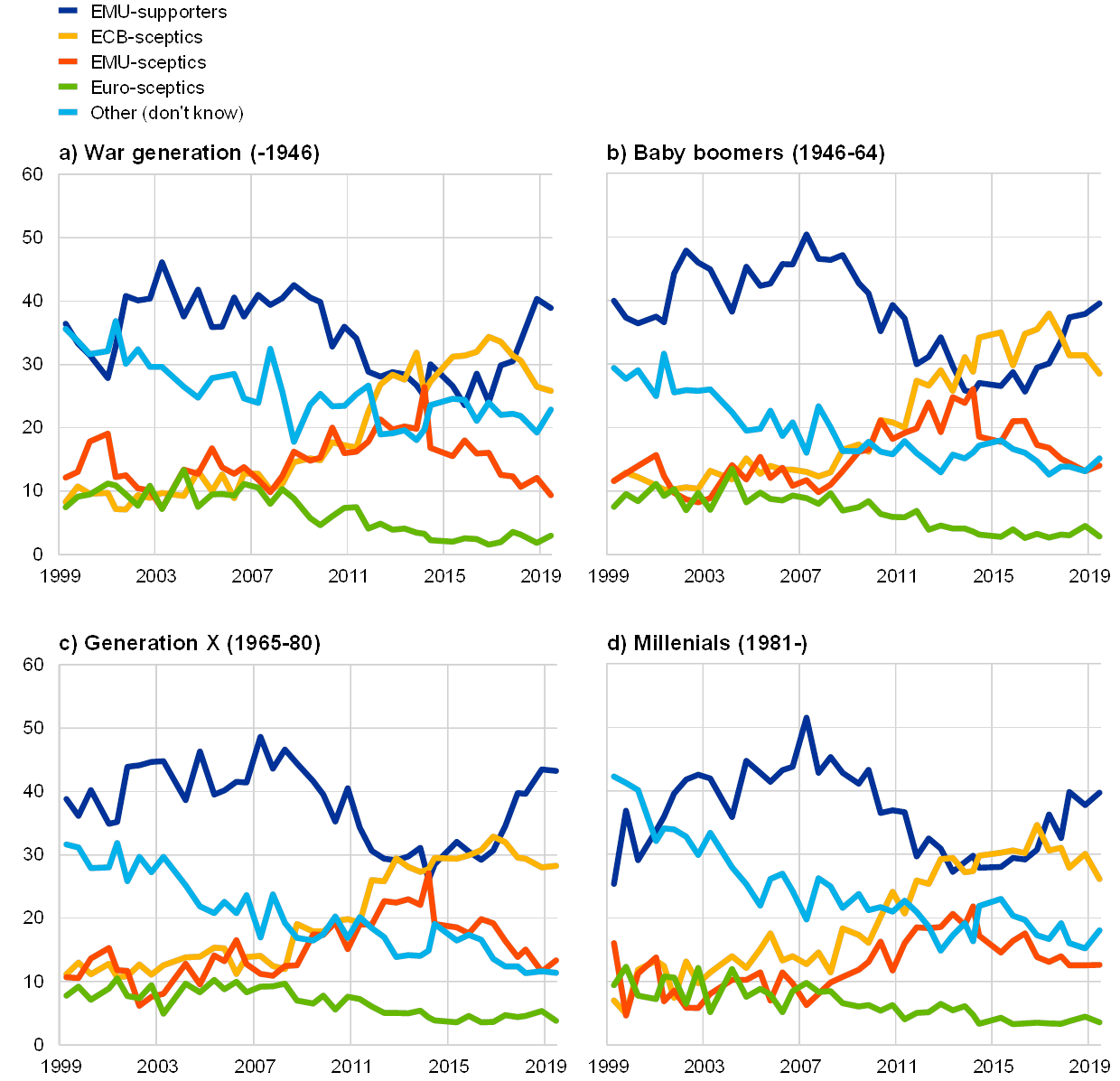

Different generations hold remarkably similar attitudes towards the euro and the ECB. Assessment of support for EMU across generations highlights that the different cohorts hold remarkably similar attitudes towards the euro and the ECB (see Chart 4). Within the different cohorts – the war generation born before 1946, the baby boomers born up to 1964, generation X born up to 1980 and millennials born after 1980 – the relative sizes of the groups of different types of supporters of EMU have been consistently close to those within the entire population over the past two decades.

The war generation, i.e. the oldest cohort, has a higher share of respondents answering “don’t know” than the other three cohorts. Prior to the crisis, this cohort also accounted for a marginally, but consistently, lower share of EMU-supporters. Over the past few years, however, this cohort has counted slightly fewer EMU-sceptics and ECB-sceptics than younger cohorts. The high share of respondents answering “don’t know” seems to suggest that older people may find it more difficult than younger cohorts to form an opinion about recent steps in European integration, be it in the form of relatively new institutions such as the ECB or the single currency. A deeper analysis of the underlying data reveals that the war generation in particular tends to respond more frequently “don’t know” to the question on trust in the ECB, and that a similar pattern can also be found in their responses to questions regarding trust in other EU institutions. So rather than being specific to recent European integration or the ECB, it appears that older people’s attitudes towards EU institutions are less well defined than those of other cohorts.

Chart 4

Typology of attitudes towards EMU by cohort

Euro area cohorts, spring 1999 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (Other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one or both questions. The birth year is approximated by the year of the survey minus the exact age of the respondent.

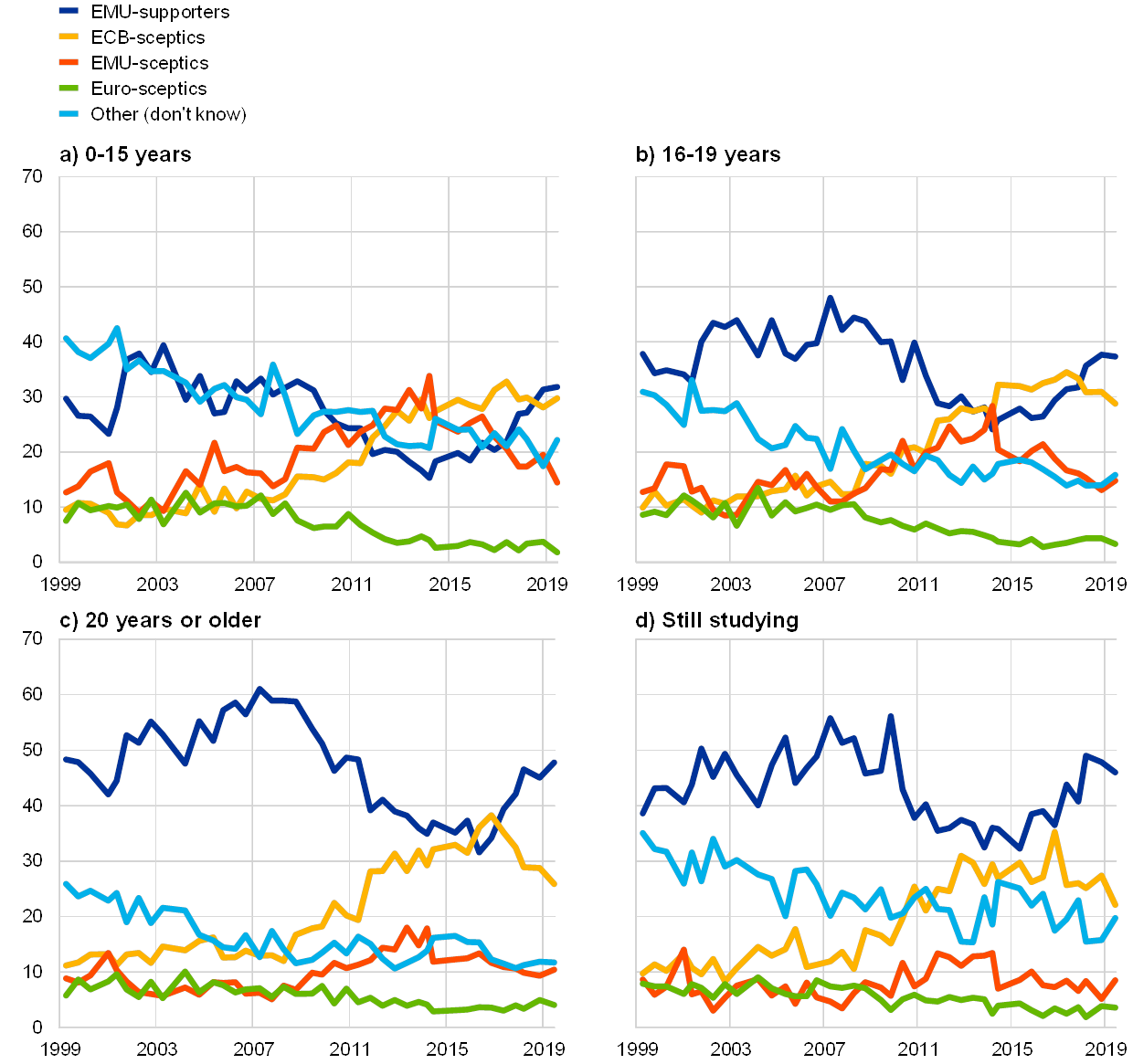

Whether respondents fall into the group of EMU-supporters is associated with their level of education and occupational background, but differs little between genders. Support for EMU tends to increase with the number of years spent in education (see Chart 5). While about 30% of people who ended full-time education at age 15 or younger are EMU-supporters, around 40% of people who finished their education between the ages of 16 and 19 fall into that category, as do around 50% of those who were aged 20 or older when they completed their education. People without any full-time education display similar but more volatile attitudes than the first group. Across these educational groups, the share of ECB-sceptics has trended upwards over time.

This pattern is also reflected in support for EMU by occupation, with managers, students, other white-collar workers and self-employed persons falling predominantly in the group of EMU-supporters, followed by retirees, while manual workers, house persons and unemployed persons are 10-20 percentage points less likely to be EMU-supporters and comprise an almost equal number of ECB-sceptics.

Men and women hold largely similar attitudes towards the ECB and the euro, with the main difference being that there is a somewhat smaller share of women in the group of EMU-supporters. Women also responded “don’t know” more often in the Eurobarometer survey (results not shown; the gap between men who responded “don’t know” and women who responded “don’t know” was about 5 percentage points).

Chart 5

Typology of support for EMU by educational level

Euro area, spring 1999 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (Other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions. The categories correspond to the answer to the question “How old were you when you stopped full-time education?”

4.5 Economic perceptions and support for EMU

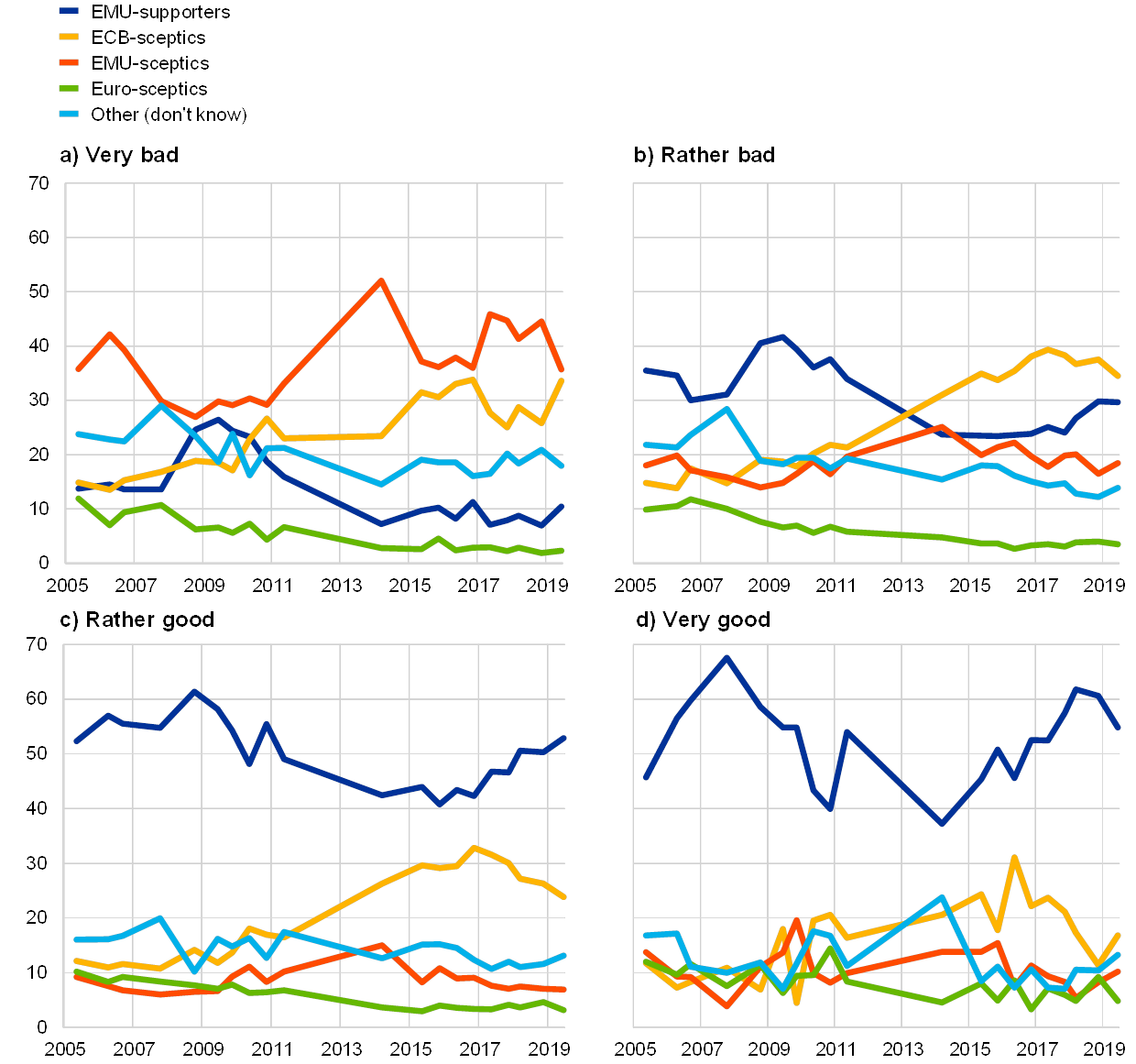

Support for the euro and the ECB is higher among citizens with a more positive assessment of the European or national economy. While many citizens may have limited knowledge of the ECB’s precise tasks and mandate,[26] they can still be expected to be aware of the ECB’s general role in the macroeconomic environment and to draw on their assessment of the economic situation to form opinions on issues related to Economic and Monetary Union. Indeed, in all the years under analysis, EMU-supporters are the dominant group among those who see the European economy as being in a good or very good state (Chart 6). Nevertheless, irrespective of respondents’ assessment of the European economy, the group of EMU-supporters shrank in the aftermath of the crisis, with the steepest decline observed among those with negative views on the state of the European economy. In effect, in late 2019 EMU-sceptics dominated among those who believe the European economy to be in a very bad state. Those who believe the European economy to be in a rather bad state mostly seem to have little confidence in the ECB, with ECB-sceptics representing the largest group since 2011. Very similar patterns can be observed when decomposing support for EMU by respondents’ perceptions of the domestic economic situation (not shown).

Chart 6

Typology of support for EMU by perception of the current situation of the European economy

Euro area, spring 2005 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions. The categories correspond to the answer to the question “How would you judge the current situation in each of the following? The situation of the European economy.” Missing observations for autumn 2011 to autumn 2013.

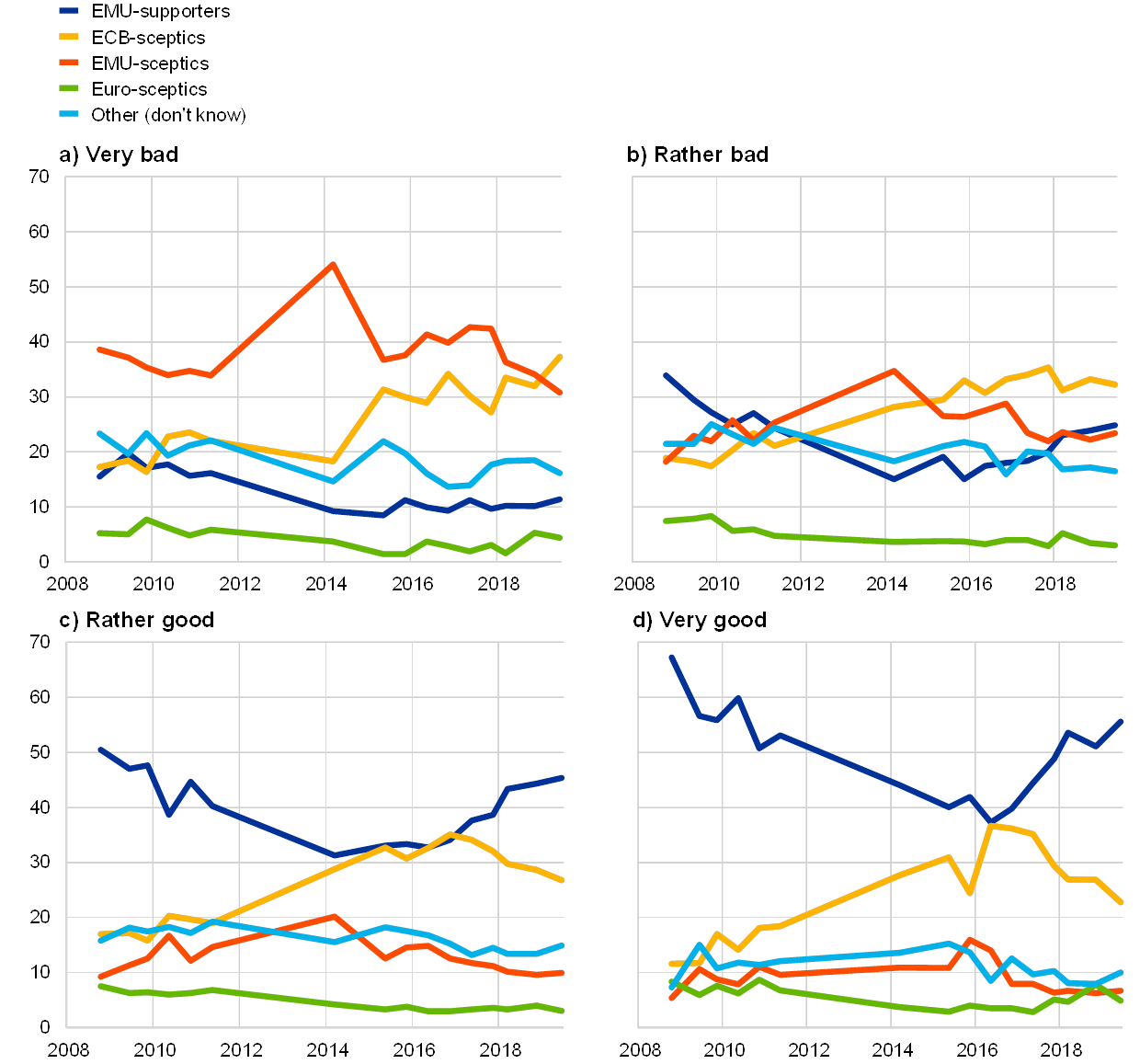

Citizens who are satisfied with their financial situation tend to be more supportive of the euro and the ECB. For almost all years under analysis, EMU-supporters were the largest group among respondents who judge the current financial situation of their household to be good or very good. It should be noted, however, that the share of ECB-sceptics approached that of EMU-supporters in 2015-16 (see Chart 7). A reverse picture emerges among respondents who are very dissatisfied with their household’s financial situation: EMU-supporters represented just over 10% of respondents in this group in late 2019 in a further decline from the already low levels before the crisis. Among those respondents, EMU-sceptics were in the majority until recently, when ECB-sceptics became the largest group, with slightly more than 35% of respondents. The greatest movement between groups is observed among respondents who assess their household finances as “rather bad.” While EMU-supporters were in the majority prior to the crisis, their numbers dropped to a low of 20% in 2011 and 2015, while the number of those distrusting the ECB and those losing confidence in both the ECB and the euro increased in parallel. Since 2014 the euro regained support, while the ECB still has to recover trust. In 2019 ECB-sceptics thus remained in the majority, accounting for just over 30% of respondents.

A similar picture emerges if we assess the prevalence of different groups of sceptics and supporters of EMU by respondents’ ability to pay bills (not shown). While EMU-supporters are by far in the majority among respondents who do not experience any difficulties making ends meet, they remain the minority among those who face difficulties paying bills most of the time. More than 30% of respondents in this group now fall into the category of ECB-sceptics.

Chart 7

Typology of support for EMU by perception of the current situation of the household economy

Euro area, autumn 2008 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (Other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions. The categories correspond to the answer to the question “How would you judge the current situation in each of the following? The financial situation of your household.” Missing observations for autumn 2011 to autumn 2013.

4.6 European attitudes and political orientations

Citizens’ attitudes towards the EU are highly correlated with their views on the euro and the ECB. The euro and the ECB are part of the EU’s institutional framework and policymaking at the European level, so one would expect that attitudes towards them are shaped by citizens’ overall attitudes towards the European project. This is indeed supported by the data. Taking citizens’ image of the EU as an indicator of their general attitude towards the EU and matching it against the typology of attitudes to EMU, one finds that the largest share of citizens with a negative image of the EU also tend to be EMU-sceptics, while an overwhelming majority of those holding a positive image of the EU tend to be EMU-supporters (not shown).

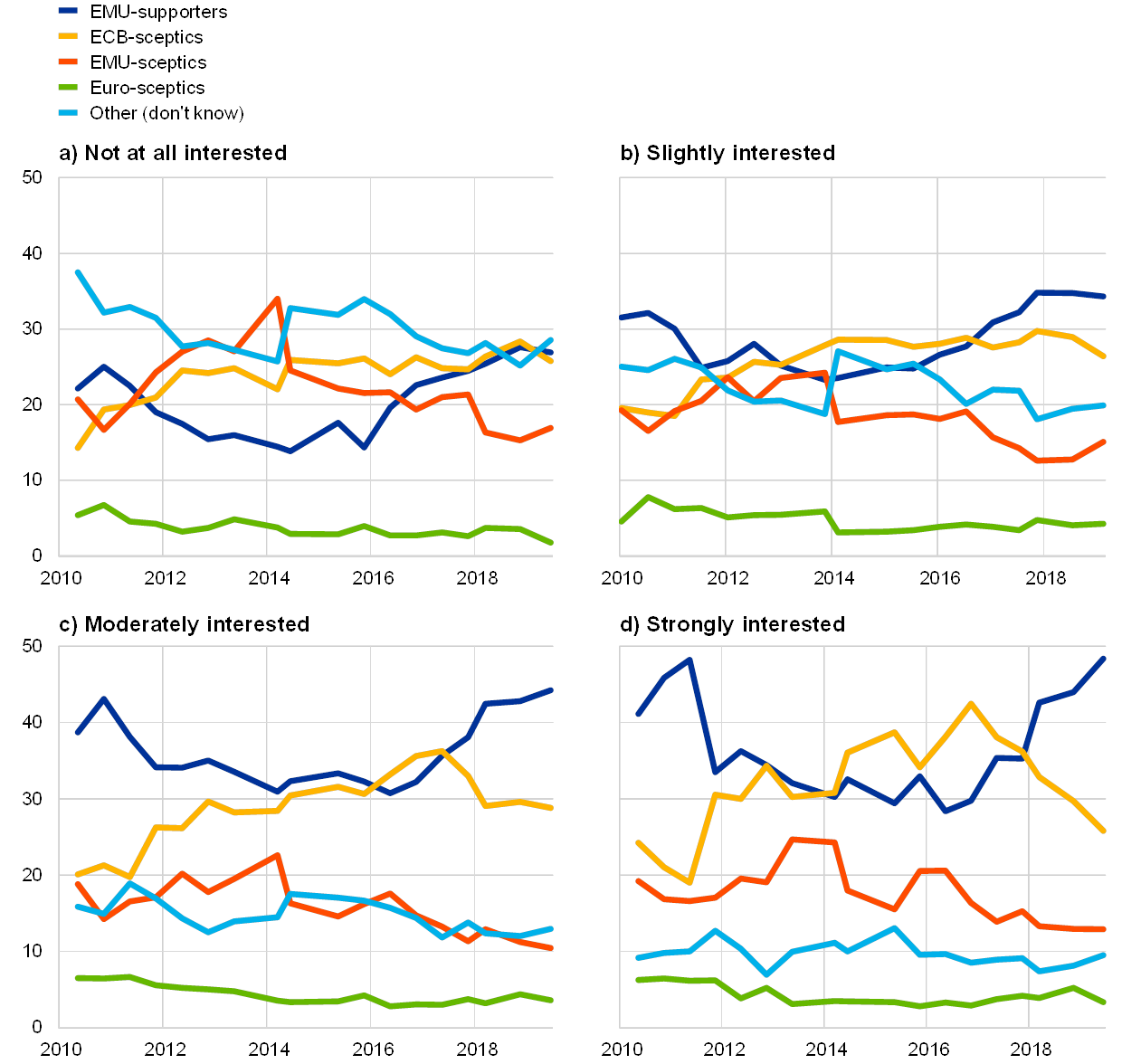

Moreover, political interest seems moderately related to support for EMU. EMU-supporters are in the majority among respondents who show at least a slight interest in political affairs, with the share of EMU-supporters increasing somewhat in line with the degree of political interest (see Chart 8). By contrast, the share of EMU-sceptics declines with increasing political interest. Notably, scepticism towards the ECB appears to be similarly strong across all respondents irrespective of their degree of political interest.

Chart 8

Typology of support for EMU by self-reported political interest

Euro area, spring 2010 – spring 2019

(percentages)

Sources: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: The typology contains four groups: the first group neither supports the euro nor trusts the ECB (EMU-sceptics); the second group supports the euro, but does not trust the ECB (ECB-sceptics); the third group does not support the euro, but trusts the ECB (euro-sceptics); and the fourth group supports the euro and trusts the ECB (EMU-supporters). A fifth group (Other) includes those who answered “don’t know” to one of the two questions. The categories correspond to an index of political interest that is constructed from the answers to the question “When you get together with friends or relatives, would you say you discuss frequently, occasionally or never about…? 1) National political matters; 2) European political matters; 3) Local political matters.”

5 Conclusion

Trust in the ECB and support for the euro have diverged in recent years. The share of the euro area population that supports the euro remained relatively steady throughout the economic and financial crisis starting in 2008-09 and by late 2019 had trended upwards to reach an all-time high. By contrast, the share of citizens trusting the ECB fell with the onset of the financial crisis and then recovered partially to a neutral level.

This disconnect can be further examined through the lens of the typology of attitudes towards EMU. Whereas EMU-supporters are found to represent the largest share of the euro area population and remained so during the crisis, the share of ECB-sceptics rose significantly during the crisis, while the share of EMU-sceptics also grew. By contrast, the percentage of euro-sceptics has remained relatively low. This illustrates rather powerfully that citizens distinguish between the euro and the ECB, and have different expectations of them. It also shows that the drivers of support for the ECB are distinct from the drivers of support for the euro. At the same time, the fall in trust in the ECB from very favourable pre-crisis levels has to be seen as part of a wider development of declining trust in public institutions in Europe in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

A breakdown of support for EMU along sociodemographic lines sheds light on who tends to support EMU and who does not. Exploring types of support for EMU along different sociodemographic lines – notably geography, age and education, as well as respondents’ perceptions of the economic and financial situation and broader attitudes towards the EU – reveals which parts of the euro area population are more or less likely to support EMU. While the univariate form of this analysis neither estimates the strength of correlations nor controls for confounding factors, the patterns it reveals over time allow possible reasons for the disconnect between trust in the ECB and support for the euro to be deduced.

The analysis suggests that popular support for EMU – in particular, trust in the ECB – hinges to a large extent on citizens’ perceptions of their personal financial situation and the overall economic situation. Perceptions of the state of the national and European economies and individuals’ financial situation are highly correlated with support for EMU and, in particular, trust in the ECB. This finding is further corroborated by the geographic distribution of support for EMU, which reveals a considerably higher share of EMU-sceptics and ECB-sceptics in euro area countries that were more affected by the crisis. Similarly, support for EMU varies strongly with education and occupation, with more years in education and higher-skilled occupations – important determinants of one’s personal material situation – being associated with greater support for EMU, despite a recent uptick in the share of ECB-sceptics across different education levels.

By contrast, other sociodemographic indicators seem to be less relevant for support for EMU. There is no marked difference in patterns of support for EMU between genders or across age cohorts, with perhaps the minor exception of the war generation, which accounts for a smaller share of EMU-supporters overall, but a higher share of “don’ know” answers. Among the sociodemographic indicators considered, political interest appears most relevant, as support for the EMU appears to be somewhat greater among respondents who are more interested in politics.

While the high and steady level of support for the euro is good news for the single currency, the sensitivity of support for the ECB holds important lessons on how citizens view and assess the performance of the central bank. The findings lend support to the hypotheses that support for the ECB is strongly related to perceptions of economic outcomes, but also to cognitive factors and material interests related to education or occupation. While the analysis shows that trust in the ECB is vulnerable to economic outcomes – potentially including those beyond the ECB’s control – it also suggests that trust in the ECB can be improved by the institution providing information on its tasks and objectives, and by continuing to pursue its mandate of maintaining price stability, thereby safeguarding citizens’ purchasing power.

More inclusive communication and efforts to improve general understanding of the ECB’s mandate and tasks may help foster trust in the ECB. In particular, given the heterogeneity in support for the EMU and scepticism of the ECB observed between and within countries, as well as among different parts of the population, making communication more accessible to people with differing levels of education and prior knowledge, and also addressing the concrete concerns of citizens in different parts of the euro area – such as the ECB’s role in economic outcomes – can enhance trust in the ECB. The heterogeneity within countries highlights the need to reach out beyond capital cities. In addition, action to increase knowledge not just on personal finances, but also on how financial markets and central banks function, including the services they provide to citizens in their everyday lives, for example in the fields of payments or cash provision, may further improve citizens’ understanding of and trust in the ECB and its policies.

Enhanced communication efforts to foster trust in the ECB will be in its interest. Higher levels of trust in the central bank not only help steer inflation expectations and promote trust in the currency, thus supporting the effectiveness of monetary policy, but also preserve the central bank’s independence by shielding it from political pressures. In the context of EMU, having a more trusted and hence more effective central bank also encourages citizens to perceive European economic integration as successful and thus fosters greater popular support for significant economic and financial, as well as political, steps towards greater integration. In turn, such steps could further enhance the effectiveness of the ECB’s policy and improve the overall welfare of euro area citizens.