Nearly 200 Russian civilian vessels show suspicious behaviour in the North Sea. Some of them have been linked to spying on seabed infrastructure since 2014. A joint investigation between Follow the Money and De Tijd mapped the most suspicious events and shows why little can be done about them.

THIS ARTICLE IN 1 MINUTE

- Russian ships are trying to gather intelligence on the location of essential cables and pipelines at the seabed of the North Sea in order to potentially sabotage or disrupt them.

- Russia uses fishing boats, cargo ships, oil tankers, research vessels and pleasure yachts to do so.

- Follow the Money and Belgian newspaper De Tijd have mapped all possible espionage, sabotage and other suspicious activities of Russian ships in the North Sea since 2014.

- There were 1,012 Russian-flagged ships active in the North Sea over the past decade; almost 60,000 times they hung around seemingly aimlessly; 950 times within 1 kilometre of cables or pipelines. 167 civilian Russian vessels were involved.

- European countries have few options to intervene even if suspicions of espionage are confirmed

Russian ships are suspected of having engaged in almost 1,000 incidents of spying in the North Sea, a cross-border investigation has found.

The North Sea is of critical importance for European countries, with data, power and communication cables, as well as oil and gas pipelines running on the seabed.

In recent months, Russian military research vessels have repeatedly been suspected of sabotage. The Russian research vessel Admiral Vladimirsky has frequently been spotted in European ports and caught behaving abnormally, while navy spy ship Yantar made international headlines ever since it went into service in 2015 for its capacity to target underwater infrastructure. The Yantar carries submarines on board that are allegedly used for maintenance and repairs below the surface, but that are capable of cutting cables at a depth of several kilometres.

Late last month a Russian submarine was suspected of navigating in Irish waters. Concerned about potential sabotage of cables and pipelines, France, Norway and the United Kingdom helped the country, which doesn’t have the military capacity to do so, hunt the vessel.

These aren’t isolated incidents: while the ships have been facing increased scrutiny since Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has been seeking to spy on the locations of cables and pipelines, with the potential to disrupt data and energy exchanges, for years.

Since 2014, the country has been deploying an increasing number of civilian vessels to scour the North Sea, several security experts told FTM.

“Authorities have found listening devices on fishing vessels,” said political scientist at the University of Copenhagen Mariia Vladymyrova, who has spent years researching Russia’s activities. “This tactic is not new. It was also used during the Cold War, but since 2014 we have seen a clear increase.”

Follow the Money and Belgian newspaper De Tijd mapped all incidents of possible espionage, sabotage and other suspicious activities on the North Sea over the past decade, revealing staggering numbers. The investigation found 1,012 Russian-flagged ships that have been active on the North Sea between 1 January 2014 and 1 April 2024: fishing boats, cargo ships, yachts, oil tankers, and scientific research vessels.

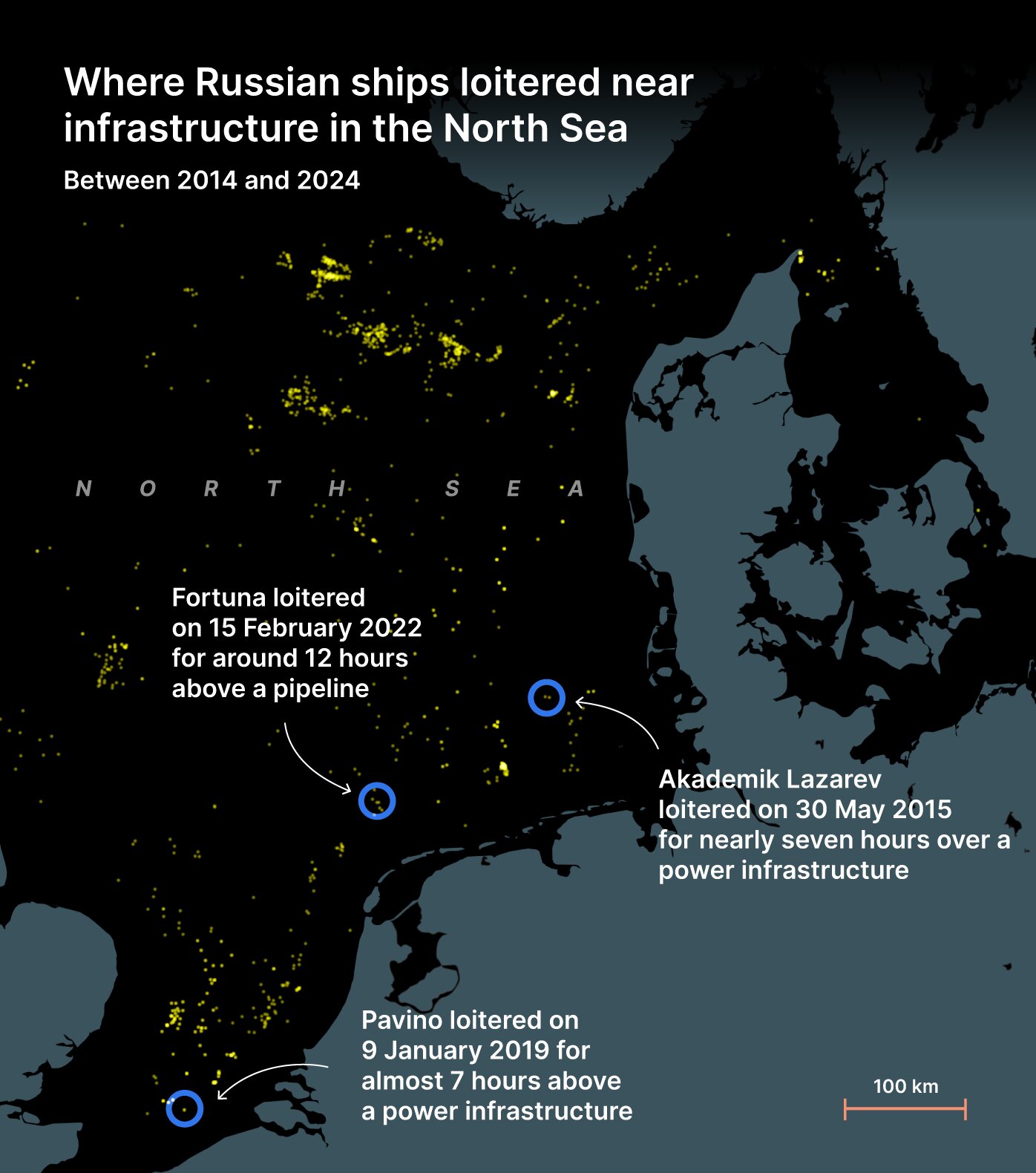

With the help of data collected by nonprofit organisation Global Fishing Watch, Follow the Money identified 60,000 so-called loitering events by Russian ships: the vessels were circling in place, drifted aimlessly, or took routes that deviated from their normal route.

Many of those incidents can be explained by benign shipping activities – such as when a ship has to sail through bad weather conditions – but they become more suspicious when they take place near critical infrastructure.

They can indicate that the vessels, instead of transporting cargo, fishing or doing biological research, were attempting to get information on where the critical infrastructure is and what the weak spots may be.

Follow the Money found 950 of such events, having taken place within 1 kilometre of cables or pipelines: near enough to spy on the exact location of critical infrastructure, or being able to cause damage to them. They were carried out by 167 civilian Russian vessels.

When Russian ships enter the North Sea, the coastguards and security services of the countries concerned are on high alert.

“Russian ships are suspicious in themselves, even if they maintain a very normal sailing pattern. Because every Russian ship, even if it works for a private company, works for the Russian government anyway,” said Thomas De Spiegelaere, spokesman for the Maritime Security Cell of the Belgian Federal Public Service of Mobility and Transport.

Belgium, for example, has a list of 1,500 Russian ships they regularly monitor because they fly under flags from countries with lax law enforcement, or because they’re suspected of espionage, smuggling, and other crimes.

Suspicious behaviour

Russia makes no secret of using commercial ships for military purposes. After the invasion of Ukraine, Putin tightened its Maritime Doctrine. The updated code, which defines the objectives of the Russian navy, now says that civilian vessels, including fishing boats and transport ships, are of “strategic importance for increasing maritime preparedness” and may be used for “special operations carried out by the armed forces of the Russian Federation”.

Sailors are trained in advance for this purpose and their ships are adapted if necessary, according to the code.

Russia does this to expand its capacity to surveil European infrastructure under the sea, political scientist Vladymyrova said.

“Russia has only a limited navy, but it has a large fishing fleet, so they deploy it,” she said.

Maritime services also see Russian merchant ships sail through the North Sea – mainly from the Baltic Sea towards the Mediterranean of Black Sea – under the escort of Russian military ships more and more frequently, De Spiegelaere said.

Fishing boats and transport ships may be used for “special operations carried out by the armed forces of the Russian Federation”.

But even without a military escort, Russian ships are regularly suspect.

Russian ships are monitored from the moment they enter the North Sea countries’ Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), an area between some 22 kilometres and 370 kilometres from shore. This is done using an automatic identification system (AIS) – a location signalling system that is installed on the ships themselves – and software that monitors the movements of ships and predicts routes and arrival times.

Diving deep

The cat-and-mouse game in the North Sea has been going on since at least the early 1950s. Around that time, the Soviet Union began a large-scale programme to map infrastructure with the aim of being able to commit sabotage if war came, according to intelligence expert Kevin Riehle.

By default, a security officer sailed on all Soviet ships to monitor the crew, but also worked for the intelligence services. In the 1990s, this type of intelligence gathering declined, but since about 2014, there has been a resurgence of espionage and sabotage activities at sea.

Besides civilian ships, Russia also deploys military assets for espionage and sabotage. These include the crew of divers of the so-called GUGI , a group of commandos under the GRU military intelligence service. These divers operate at great depths and have their own (dive) boats. Military research vessels, such as the Yantar, are also deployed to map infrastructure around the world and also carry small submarines.

These commands and ships also target military infrastructure at sea. For example, the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) has been operating since the early 1950s. With this network of hydrophones, located largely in the Atlantic, the US and British navies try to detect enemy submarines. A series of these secret hydrophones are said to lie in the gaps between the UK and Iceland and Iceland and Greenland. There are also tens of thousands of kilometres of US military communication cables on the seabed used by NATO.

Most ships continue their normal route, certain behaviour makes the authorities’ alarm bells go off.

One of the tell-tale signs of clandestine activity is when the AIS equipment is switched off and the ship drops off the radar, reappearing somewhere completely different a few days later.

Then there are other questionable behaviours, such as deviating from their shipping routes or slowing down without apparent reasons. That’s suspicious because they don’t make economic sense: they’re more expensive because more fuel is needed and crews have to be paid for longer, according to De Spiegelaere.

One such case is that of the Arctic Spirit, which, in June 2019, sailed on a straight course in the North Sea between Denmark and the United Kingdom, but then started drifting over data cables for several hours in between.

One possible reason is that ships have to slow down when they want to deploy underwater drones, as the latter can only handle a speed of some 3 to 5 knots (about 5.6 to 9.26 km/h) – down from the usual speed of 20 knots (about 37 km/h).

These events become especially suspicious when they take place near critical infrastructure: gas and oil pipelines, wind farms, data cables. (Russia also seems to keep a close eye on NATO exercises – there is always one or two Russian ships sailing nearby.)

One of the civilian Russian ships that made such suspicious manoeuvres over European infrastructure is the Sirius. Built in 1978, the 87-metre-long refrigerated cargo ship is owned by Russian company Norebo.

Its home port is Murmansk, which is also a major naval base.

In 2022, for example, the Sirius and the Atlantic Lady, another cargo ship, seem to aimlessly sail up and down part of the Dutch coast, crossing numerous telecommunications cables before entering port.

Norebo told Follow the Money it had been delayed because of Dutch harbour authorities.

The Sirius is known to Western security services primarily for possible smuggling and violating sanctions, according to the Belgian Maritime Cell, but such a manoeuvre also points to possible espionage.

LLC transit, the owner of the Tavayza, said the vessel had to stop because of damages and because of bad weather conditions.

Cutting cables

What makes detection of espionage difficult is the fact that there might also be a legitimate reason for the suspicious behaviour.

The most common explanations are bad weather (it is customary to sail around in circles, because lying at anchor is too dangerous) and engine troubles. Other explanations: civilian research vessels doing ecological surveys might sail along infrastructure as they contain shells and small animals that create an ecosystem interesting to study. AIS signals can be faulty.

“With those [repair] robots you can also do other things, for example cut cables.”

“Ninety-nine per cent of the suspicious behaviour will probably be logically explainable, but we still have to look into it,” De Spiegelaere said.

But spying ships can also use these issues as excuses: Russian ships, for instance, sometimes on purpose arrive several days early, the Belgian Maritime Security Cell said; they work on the engine to linger around the area for longer, giving them a great opportunity to map the seabed.

“Some ships have small submarines on board to make repairs to the hull of the ship themselves,” De Spiegelaere said. “But with those robots you can also do other things, for example cut cables.”

But even if authorities are near certain that something dubious is going on, international law doesn’t allow them to do much more than keep a watchful eye on the ships.

Still, in some cases, if there’s enough cause for concern, coastguards, together with police or the marine, can board a vessel.

There, they often see their suspicions confirmed, De Spiegelaere said: they find radio equipment not needed for fishing, underwater drones, or sonar signal scanners that are used to map the seabed of the tracked path to detect cables.

But even then, the authorities aren’t allowed to go much further than that. In their Exclusive Economic Zones, states mainly control resources in the seabed, but ships have the right of free passage here.

“We can board, we can make a determination there, but going beyond that is very, very difficult,” De Spiegelaere said.

That also applies even if the vessels are found to have been tempered with the cables, according to Christian Bueger, professor of international relations at the University of Copenhagen and a specialist in maritime security.

“There is no criminal offence in the German law for the exclusive economic zone,” he said. “So basically if you find a Russian vessel tempering with the pipeline or a cable, the only thing that the federal police can do is ‘hello, can you please stop that?’ and they don’t have any power to arrest.”

But to change the law, the United Nations Convention Law of the Sea, is difficult, De Spiegelaere explained. That’s because it has been signed by 169 parties who would all have to agree to the new rules.

“While we are on it and all eyes are on that ship, the real spying may then be taking place elsewhere”

And giving countries more wide-reaching powers to protect their maritime territory is a security risk in itself, he said.

“If we include tools in it to intervene against suspicious ships, we are also giving powers to, say, Iran and China to intervene on our ships. And those countries, certainly Iran, could misuse those to hijack ships or arrest the crew,” he said.

Experts argue that most of the suspicious behaviour does not end in actual sabotage, but is meant as a distraction.

A ship like the Yantar, for example, is effectively always being tracked because of its espionage activities in the past. If it takes unusual sailing routes, this could serve as a red herring to hide other issues.

“While we are on it and all eyes are on that ship, the real spying may then be taking place elsewhere,” De Spiegelaere said.

It can also serve as a warning to European authorities.

“It’s about putting the threat out, or demonstrating [our] vulnerability: ‘Hey, we can sail along your cables and cut at any time.’ You literally cannot do anything,” maritime security expert Bueger said. “It’s just about keeping us busy, worrying about the threat. And this works really really well.”

Still, authorities can’t simply ignore this behaviour, political scientist Vladymyrova said. “With relatively small incidents and few resources, the Russians manage to keep Western authorities so busy. We are playing their game,” she said. “There is no alternative, otherwise a real security problem may arise.”

Creative ways to spy

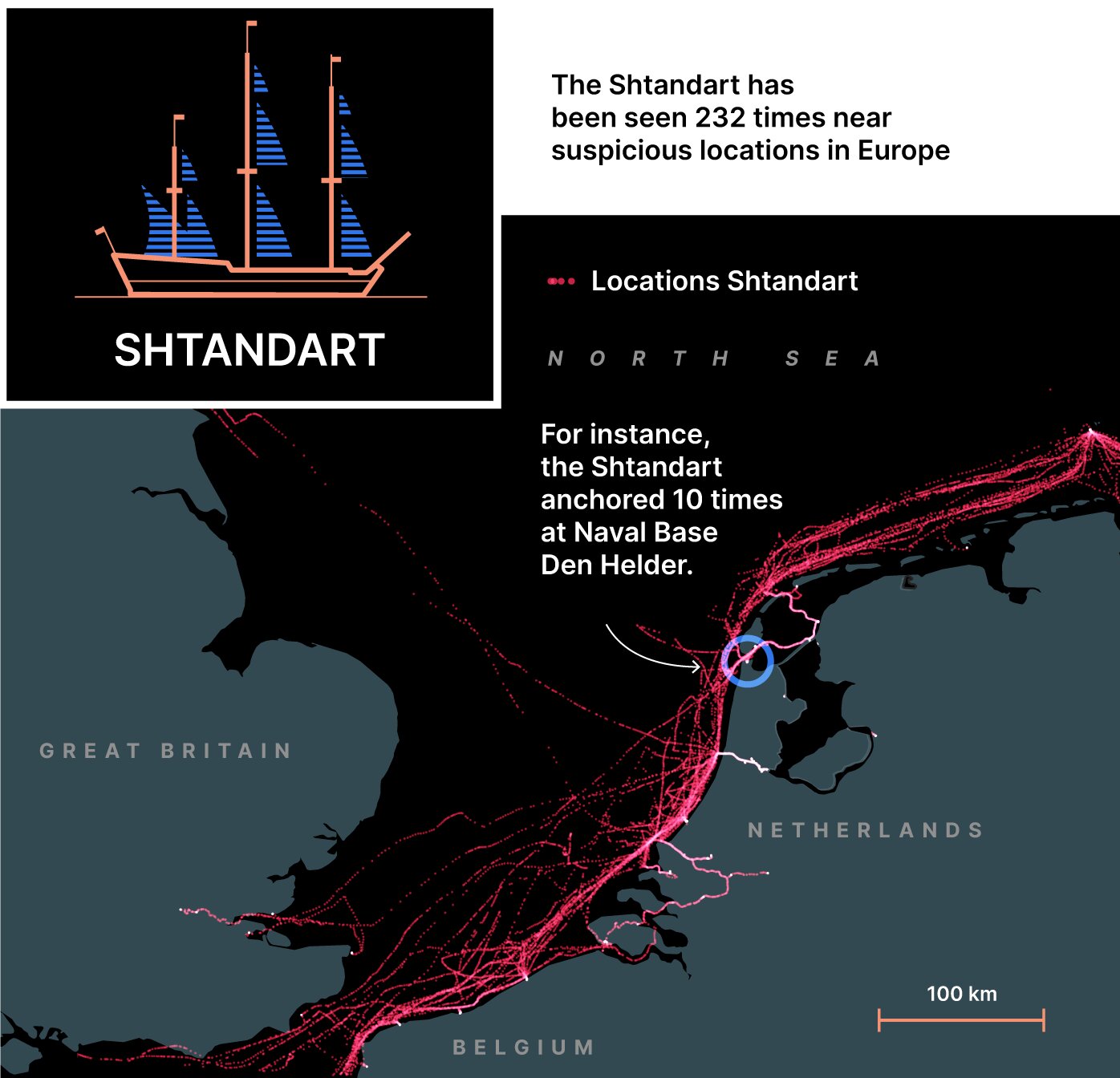

It’s not just commercial ships that Russia uses for apparent spying activities, however: authorities also increasingly notice the use of sailing vessels recently, the Belgian De Spiegelaere said.

These ships are even more difficult to track because they don’t have to use an AIS signal and often show unpredictable behaviour because they’re dependent on how the wind blows, for example. They zigzag when they have to cruise upwind, or they throw their anchor somewhere because the crew wants to scuba dive. And that’s all legal.

Tourists often accidentally sail in areas where they are not allowed, such as between wind farms. They claim that their engine failed or that they were drifted by the wind.

“There are hundreds of excuses for why they do that. And then suddenly they are in areas where they can do a lot of harm. For example, cutting a cable with an anchor,” De Spiegelaere said.

The Shtandart, a replica of the frigate of the same name built by Russian Tsar Peter the Great in the 18th century, seems to be one of the non-commercial boats that could be used for spying activities. It showed up more than 230 times at suspicious locations in Europe over the past decade. Of those, it showed up in a 10-kilometre radius of NATO boats almost 90 times, the data shows.

The technical possibilities for espionage and sabotage are also growing, security experts warn.

They fear that in the future the Russians will not only have the ability to sabotage cables, but also to eavesdrop on data traffic passing through the cables and potentially even put information on them without damaging the cables, for example by placing equipment on them that transmits false information.

The invasion of Ukraine pushed European countries to step up their game.

In April this year, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Norway, the UK, and Denmark signed the North Sea Security Pact. With this, they agreed to exchange information.

According to De Spiegelaere, this was already happening on an informal scale. This “now formalises that we not only may, but must share it with each other,” he said.

To intervene, however, is still not possible.

How we investigated this

For this investigation, all Russian-flagged vessels operating in the Exclusive Economic Zones of six North Sea countries between January 2014 and April 2024 were considered: Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Norway and the United Kingdom. Active means fishing, long-term floating around or port visits. These are not all Russian vessels that were active during the period, as some are flying other flags (e.g. that of the Marshall Islands) or have not stopped anywhere. In total, we collected information from 1,012 vessels from Global Fishing Watch.

From over 100 Russian vessels, we downloaded the actual sailing route. This is a collection of coordinates sent using the Automated Identification System (AIS). AIS coverage is not always good, especially in the early years. We also collected the location of infrastructure via MapStand and EMODnet to compare it with vessel movements.

Suspicious movements were submitted to experts and – where possible – verified with AIS sources other than Global Fishing Watch. Through Marine Vessel Traffic and from public sources, we investigated the location of NATO ships over the years and mapped the locations of military bases and exercises.

A detailed justification and the programming code used can be found on GitHub.