“I worry what the House could do” on Chinese investment screening, Sen. Bob Casey (D-Penn.), a sponsor of the Senate’s outbound investment bill, said on Capitol Hill in November.

Free traders have the opposite concern. As the Biden administration and Congress try to decrease exposure to the Chinese economy, lawmakers like Murphy warn that large American corporations could be at a disadvantage to firms in allied nations — particularly if they don’t follow Washington’s lead.

“If a U.S. company isn’t making as much profit as its competitors are, it’s gonna be really hard for it to … make bigger investments and out-innovate the Chinese,” she said, adding that the government’s push to subsidize chipmakers and other critical firms has perils in itself.

“The industrial policy, as we saw most recently with the CHIPS bill … relies on government to pick winners and losers, and it takes only one Solyndra to cause a real problem with our industrial policy,” she said, referencing the failed solar company that bedeviled the Obama administration’s clean energy efforts. “And so it’s a perilous time, and a perilous strategy that requires everything to go right.”

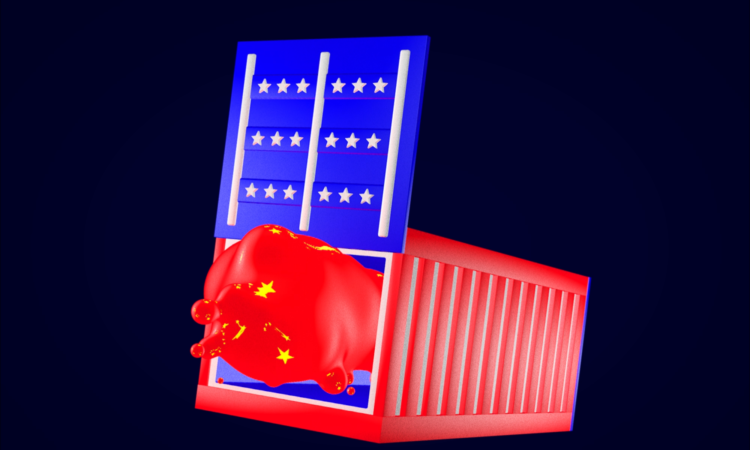

The decoupling conundrum

Murphy’s concerns point to a deeper question facing Biden and Congress in the new year — just how far to drive an economic wedge between the two economies.

While all agree that the administration has escalated U.S. action against China’s tech sector, there are those who want the moves to go further — and who criticize the administration for not already upping the stakes.

In issuing the chip rules, the Commerce Department let some chip firms in allied nations off the hook. Even though they use software from American firms, making them subject to U.S. export controls, the administration decided not to force firms in the Netherlands and Japan to stop shipping chip-making equipment to China.

The concern, the administration said at the time, was that if Biden included Dutch and Japanese firms in the tech blockade, they would simply program out the American software, continuing to sell chip-making machines to China while depriving U.S. firms of their business.

“We obviously don’t have an interest in controlling technology made by U.S. companies that could be immediately backfilled by foreign competitors,” a senior administration official told reporters when the chip rules were issued, “which would simply see market share loss by U.S. firms and then PRC getting the same capabilities.”

Instead, the Biden administration said it expects allies to follow suit on their own, voluntarily issuing similar export controls that would stop their firms from enabling the Chinese chip-making sector. A deal to do so was close at hand, BIS head Alan Estevez told an industry event in late October, and should be completed by the end of the year.

But the path to that deal has been rocky, with the Dutch and Japanese making clear that they are not likely simply to follow Washington’s direction on export controls. Adding to the tension: mounting EU anger toward the industrial policies in the Inflation Reduction Act, which benefit American electric vehicle companies over European automakers.

That’s led some China hawks to say that the administration erred by not including the Dutch and Japanese firms in the first place.

“We really brought a knife to a gunfight” with the new BIS export controls, said Nikakhtar, who pushed for a more aggressive approach to China during her time at Commerce. “Why pressure [the foreign governments] when you can make it illegal?”

Even if the Biden administration can reach a chip control deal with its allies, similar issues are likely to arise as the U.S. government moves beyond the semiconductor sectors and seeks to stall or outpace China’s development in other critical sectors like biotech and clean energy. In each case, EU members will have to choose whether they continue to allow their companies to sell sensitive tech to the Chinese, or agree to follow American blockades.

“At some point, we have got to tell the Europeans that you’re either on our side or the other side,” said Lighthizer, who often ruffled feathers in Brussels during Trump’s tenure. “Europe wants to be somewhere between the two of us, and therefore they’ll be resistant if they can make a buck.”

The Europeans say that Biden’s focus on rebuilding American manufacturing — sometimes at Europe’s expense — is making cooperation even harder. EU members are fuming that Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act cuts their domestic automakers out of hundreds of billions of dollars in electric vehicle subsidies by stipulating that final assembly must be done in North America. After Biden’s promises of a post-Trump reconciliation with allies, Brussels is feeling betrayed by the action.

The new subsidies, combined with unilateral American actions on Chinese tech, “make Europe consider the U.S. as a country of concern, not too distant from China,” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, a former EU and Swedish representative at the World Trade Organization.

At the core of the disagreement is a conundrum — just how far to push the economic decoupling from China. Some, like Lighthizer, say that the U.S. should look beyond limiting China’s development in a handful of sectors, and try to reduce the overall trade deficit with the world’s second-largest economy.

“Smart guys tend to get caught up in the technology, because it’s so technical, and so futuristic and all that, but [trade in goods like] t-shirts is bad, too,” said Lighthizer. The trade deficit, he has long argued, “also builds up their technology, builds up their military and their spy network.”

“In other words, we’re funding all this horrible stuff,” he said.

That push for broader decoupling could gain steam with Republican China hawks in the next Congress, as they look for ways to paint the president as soft on Beijing. But for now, the White House’s team and its recent veterans are pushing back on that rhetoric, saying they will aim to balance the new tech conflict with China while retaining commercial ties.

“The general message we’re trying to get across is that I think the conversation about ‘decoupling’ is a little bit 2019,” Tobin said. “We need to be talking about selective disentanglement and being more nuanced, going issue-by-issue, finding common-sense steps to protect our interests while still allowing for the idea that economic and trade cooperation can bring benefits.”