The Prime Minister’s decision to spend £650m on nuclear fusion is an attempt to make up for the irreparable damage of Brexit, the head of the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) has said.

Sir Ian Chapman, chief executive of the body responsible for the nation’s fusion research, was speaking following the announcement that the UK would not rejoin Euratom’s nuclear fusion programme but would instead fund UK work directly.

This comes despite the UK rejoining the EU’s Horizon programme for science funding.

Sir Ian said the UK’s decision to pull out of Euratom, which is not an EU body but is governed by the European Court of Justice and the European Commission, in 2020 had led to British companies being blocked from bidding for contracts.

Rather than rejoin the programme part way through the current funding period, it was better value for money and much faster to fund UK research directly, he said.

“We have not been a part of [Europe’s fusion programme] for two years and nine months, and that whole time UK industry has not been eligible to win new contracts. Not only have they not won new contracts, but it has been such a long period of time, they’ve stopped bidding for work now and they’ve disengaged,” Sir Ian told a press conference on Thursday.

Euratom’s fusion work is now focused on ITER, a £17bn megaproject to build a reactor in France. Rejoining it would take “many years to rebuild a significant participation in the programme”, Sir Ian added, suggesting that UK industry preferred not to rejoin at this time.

Asked if granting £650m of direct funding instead of rejoining Euratom’s fusion programme was a case of attempting to make up for irretrievable damage from Brexit, Sir Ian said: “Yes, that’s right.”

He insisted, however, that the new investment was an exciting opportunity that would enable UK industry to play a key role in fusion. He said that direct funding also allowed the money to be concentrated on fusion, rather than distributed throughout Euratom.

Sir Ian said it was always possible that the UK might rejoin Euratom in its next funding period after 2027.

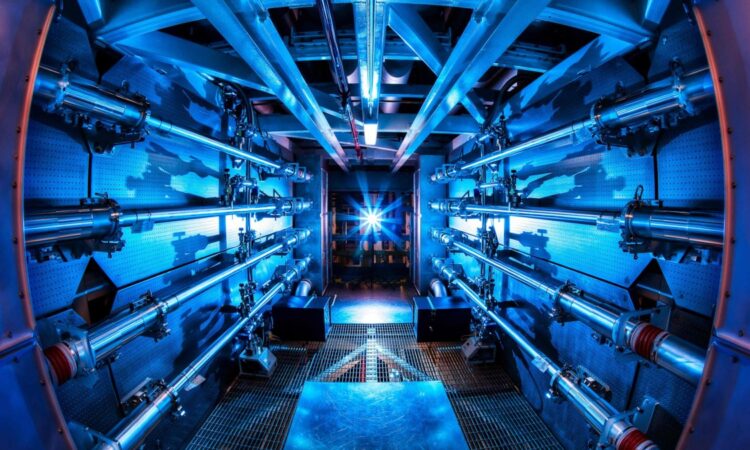

Fusion involves forcing together two atoms in the same process which generates the sun’s energy. It is distinct from fission, the current source of all the world’s nuclear power, which involves splitting atoms.

It promises clean and near limitless energy because, if it can be made to work, fusion will generate far more energy than is put into it while requiring only very small amounts of hydrogen as fuel and producing little if any long-lived radioactive waste.

It is, however, an immensely complicated undertaking due to the difficulties inherent in containing plasma hotter than the sun within a reactor.

Various different methods are being pursued for igniting the process and containing the resultant plasma.

Britain aims to have a cheap and reliable commercial form of fusion available by the early 2040s, in the form of its Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (Step) reactor.

Sir Ian said he didn’t care if Britain was not the first to reach commercial production if it was capable of building a better value reactor.

“If we have a better value proposition and we have a better economics case, then we will actually end up selling more power plants,” he said.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero was approached for comment.