Policymakers across the world are taking action to address climate change by committing billions of dollars to support efforts towards a green future. But the lack of an organised approach could set off fierce competition for people, power and resources, hampering the realisation of global green objectives.

We have seen plans to bolster greener forms of economic growth announced in the US, the EU, China, and India. Countries have stepped up efforts to gain a green competitive edge. This will entail transitioning to green products and processes, driving green innovation, and safeguarding critical mineral supply chains needed for the clean energy transition.

The ‘race to green’ began a new phase in August 2022 with the Biden administration’s landmark Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA seeks to bolster US energy security and decarbonise energy production. It includes USD 500 billion worth of spending and tax incentives for renewable energy and aims to strengthen the domestic supply of critical minerals and production of clean technologies within the US.

Other economies have enacted their own green policies:

- The EU’s REPowerEU Plan aims to reduce reliance on Russian fossil fuels with an investment package totalling almost EUR 300 billion. It will be spent on clean energy infrastructure projects, with the goal of securing the bloc’s supply of critical minerals and reaching a 45% renewable energy mix by 2030.

- China’s 14th Five-Year-Plan totals USD 4 trillion in government expenditure. Low-carbon development and innovation are a priority: the plan targets 30% renewable power, 1 200GW of wind and solar capacity and peak emissions – all by 2030.

- India’s 2023-24 Budget pledged USD 4.27 billion towards green energy projects focusing on hydrogen and solar. India is looking to decarbonise its vast transport system, using green bonds to fund the transition.

IRA impact

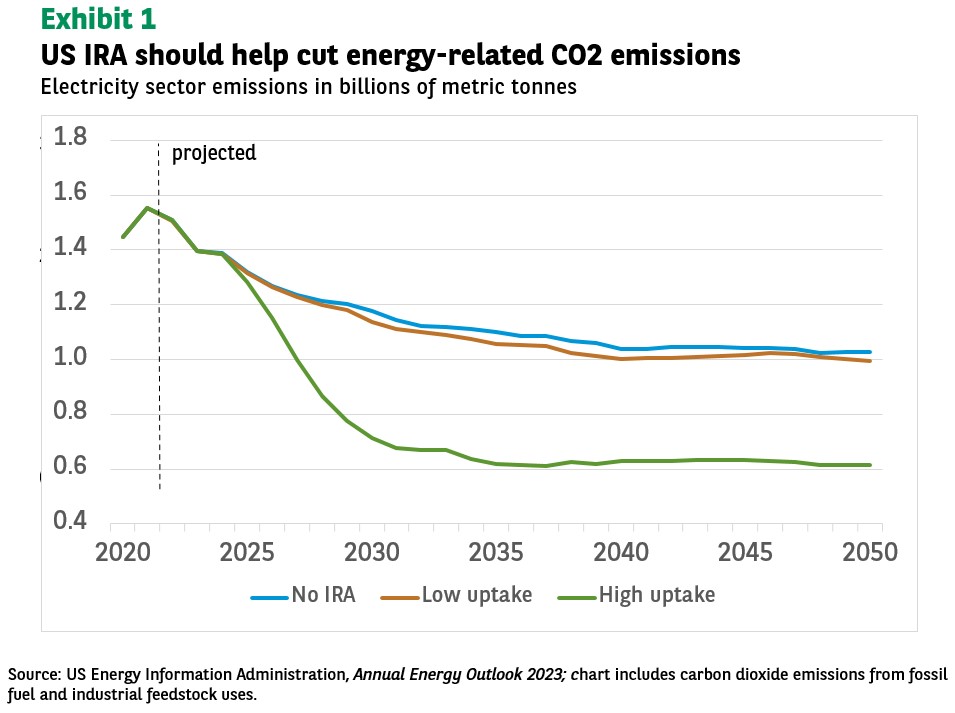

Research on the IRA’s impact has found that economy-wide emissions should fall by 43-48% below 2005 levels by 2035 if clean energy deployment accelerates. Electricity-sector specific emissions would drop by just 27% without IRA regulations, but by 59% with sped-up clean energy deployment and a high uptake of IRA regulations between 2022 and 2035 (US EIA data; see Exhibit 1).

The legislation has had other positive effects, for example, spurring a big push for US-based electric vehicle and battery production. Projects include Vietnam’s VinFast’s USD 4 billion EV factory in North Carolina and South Korea’s Hyundai’s USD 5 billion battery plant in Georgia. EV uptake is a key focus: the US now offers a USD 7 500 tax break for purchases in a market projected to grow to USD 137.4 billion by 2028 from USD 24 billion in 2020.

As these examples suggest, foreign companies have been notable beneficiaries of the legislation. The IRA has prompted nearly USD 110 billion in clean-energy projects since it was passed, with overseas companies, largely from South Korea, Japan and China, accounting for more than 60% of the spending, according to WSJ analysis.

The administration’s goal is to shore up US supply chains for green-energy industries and to deliver affordable, clean technology energy. A recent update to IRA regulations stipulates that by 2027, 80% of an EV battery’s critical minerals should be sourced domestically or from free trade countries (FTCs). Mandating domestic production, however, may increase costs.

A focus on renewables and critical minerals

As is the US, the EU, China, and India are focusing policies on renewables in order to keep up with increasing energy demand without boosting carbon emissions.

Efforts are centred on securing – and where possible onshoring – supply chains. One contentious area is that of critical minerals, essential components in many rapidly growing clean energy technologies, from wind turbines and power grids to electric vehicles.

Demand for these minerals is expected to rise quickly as the clean energy transition gathers pace. There are growing concerns, though, about the emergence of critical mineral monopolies, resource nationalism and frayed international relations as economies strive to secure supplies and provide subsidies to domestic producers.

One of the IRA’s tenets is increasing the domestic supply of critical minerals such as lithium and manganese. However, US production has dropped to the point where only one lithium mine operates in the country. Additionally, US refining plants are ‘nearly non-existent’, while China dominates this space, processing 68% of nickel, 40% of copper, 59% of lithium and 73% of cobalt.

With the US wanting to rely less on Chinese supplies, it will have to invest heavily in domestic mining, not just advanced manufacturing. Limited lithium and manganese supplies and the IRA’s requirement of 80% US or FTC product content could mean most US EVs may need to run on nickel-cobalt-aluminium cathode batteries, says one study.

However, more local mining may fan environmental concerns over water withdrawals, greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity. Globally, nearly 1 300 mines and exploration sites are found in ‘Key Biodiversity Areas’. Of these sites, 29% extract minerals needed for the low-carbon energy transition, according to S&P analysis.

The EU is also striving to safeguard supplies of critical minerals and manufacturing capacity. Under the Critical Raw Materials Act, the bloc looks to bolster production of vital net-zero technology components to enable a speedy transition to a clean economy.

The EU’s appetite for securing critical mineral supplies is so strong that the European Commission will allow some projects to bypass stringent environmental regulations by designating them as ‘overriding public interest’.

Balancing concerns and opportunities

The US, EU, India, and China’s plans will all accelerate the eventual and inevitable transition to a greener, lower emissions economy, creating a multitude of opportunities for stakeholders including investors.

There are considerable challenges, however. A ‘race to the bottom’ could see more and more local subsidies and incentives for local players, fanning resource nationalism, triggering further protectionist onshoring and increasing geopolitical tensions.

We nonetheless believe there is still an upside given the vast sums major economies are setting aside: when it comes to climate mitigation and adaption, every effort helps.

Disclaimer

![]()