UK pension funds are the popular, and convenient, whipping boys for a range of woes hampering Britain’s financial fortunes: companies choosing to list their shares in New York instead of London; our inability to convert world-leading life science expertise into commercial, domestic success; a shortage of long-term capital to back UK infrastructure projects.

This is unfair and is unhelpful.

Defined benefit (“DB”) pension funds’ responsibilities are to ensure there is sufficient money to pay people’s pensions. If something makes sense from an investment perspective they should and, in my experience, will consider it. But they are not piggy banks to be raided for whatever happens to be the political priority of the day.

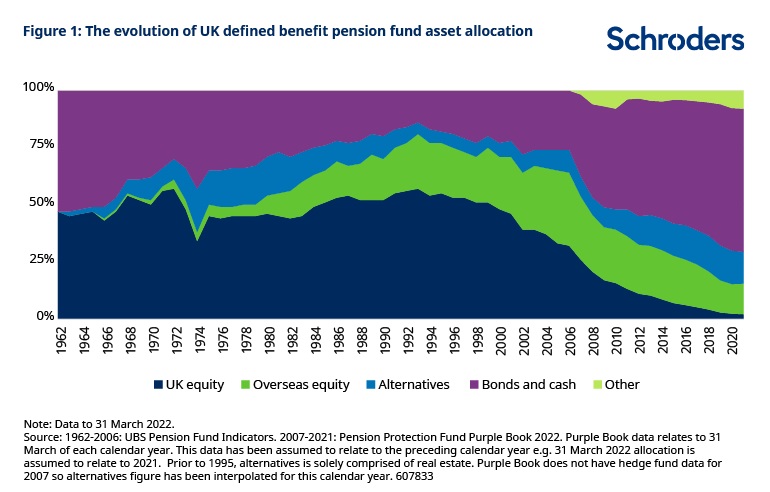

It is true that the average DB allocation to UK equities has fallen from over 50% in the 1990s to less than 2% in 2022 (Figure 1). But many of the reasons for this are grounded in sensible investment basics like diversification and risk management, not some regulatory fudge. Moreover, the suggestion that it could be reversed by a wave of a regulatory wand is misguided.

It is also a narrow view of the UK pensions landscape. DB is only one part, and a diminishing one at that. Defined contribution (DC) pension funds are in a very different place and offer a far more optimistic outlook. That is where attention should be paid to the regulatory environment. Not to force them to “buy British” but to identify where there are barriers to that money being invested productively and profitably and remove them.

“You can’t handle the truth!”

In the mid-1990s, the average UK DB pension fund had 75% of its money in equities and just over 70% of that in the UK – at a time when the UK was around 10% of the global stock market. This resulted in over 50% of the portfolio in the UK stock market.

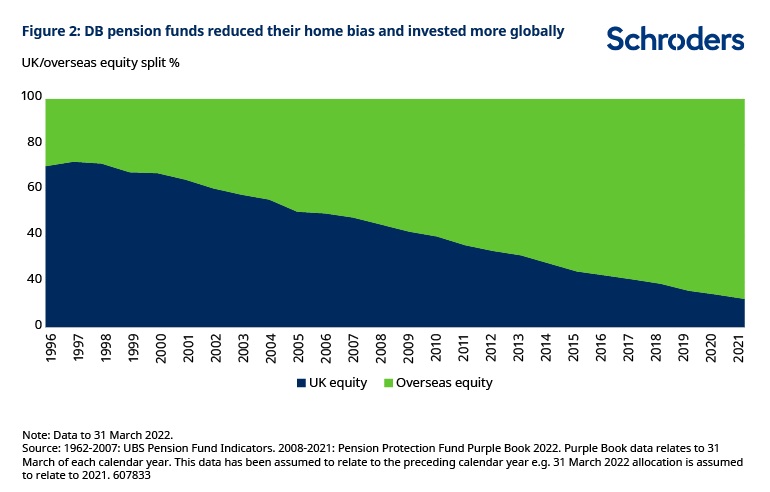

The first big shift out of UK equities arose after DB advisers and trustees sensibly decided that having quite so much of their equity portfolio in the UK wasn’t very diversified. This is especially the case given the UK itself has always been a top-heavy stock market. A handful of companies made up a large part, which remains the case today. The biggest five companies make up 36% of the total market and the biggest ten account for 53%.

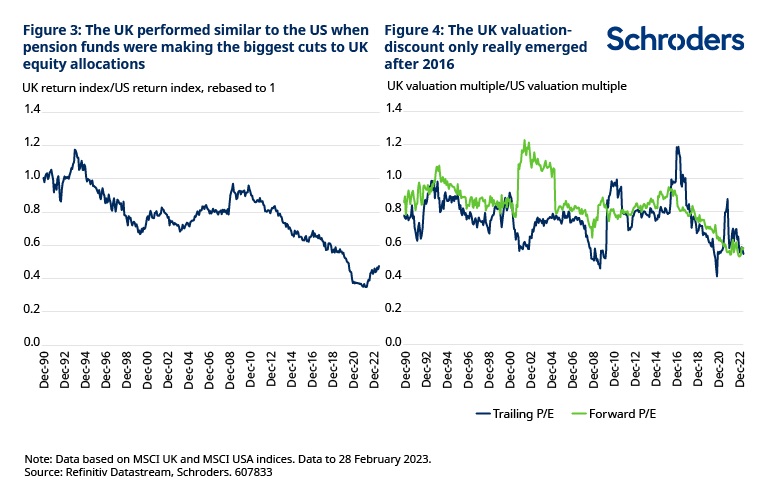

Between 1996 and 2012, UK DB funds reduced the UK from 71% of equities to 33%. This fell further to 13% in 2022 (Figure 2). So, most of the move out of the UK happened during that initial period. Despite this, returns on the UK stock market at the time almost matched the US (5.6% a year vs 6.0% a year, Figure 3).

The price/earnings multiple, a key measure of value, also went sideways versus the US for most of this period. In fact, the UK traded on a slightly higher valuation relative to the US at the end than it did at the start (Figure 4). It didn’t start falling behind on a more persistent basis until 2016.

If there was ever a time when you’d think pension fund selling should have presented a problem, that post-1996 period was it. But the market did absolutely fine compared to the US.

It’s also worth noting that geographic diversification has been a global trend. Overseas investors now own more than 50% of the UK stock market. So, while some may lament our domestic savings going overseas, we have benefitted from additional inward investment as overseas investors have done the same.

Diversification into alternative asset classes

As well as diversifying within equities, pension funds started allocating more money to alternative asset classes, such as hedge funds, private equity, infrastructure and real estate. The average allocation to alternatives rose from 6% in 1997 to a peak of 15% in 2019, before falling back slightly to 14%.

Pension trustees’ efforts to build more diversified portfolios, both within and across asset classes, have been a major contributor to less money being allocated to UK equities. None of this was regulation-driven and most people would surely agree that diversification is a good thing. UK equities returned 6% a year for the past decade, the US 12%. Past performance is not a guide to the future, and the UK is certainly very cheaply valued compared with global peers today, but this highlights why a more diversified strategy is simple investment common sense.

I love big bonds and I cannot lie

We can’t talk about DB pensions without talking about bonds. And it is absolutely the case that they have been buying bonds in a big way. The average allocation rose from about 20% in 1996, to 50% by 2012, to 63% in 2022. But again, the bulk of this transition took place at a time when UK equities were doing fine.

Critics within government should also remember that, by buying these bonds, the UK’s DB pension schemes have been giving the government huge sums of money for 10 years to be spent on the UK’s wider political priorities. Those arguing for DB to abandon bonds in favour of equities should also be careful what they wish for. Last Autumn gave a taste of what could happen, with risks of the bond market breaking down and to financial stability.

It is also naïve to suggest that pension funds could or should ignore bond yields entirely when thinking about the value of their liabilities. Only 10% of private sector DB schemes in the UK are open to new members. They increasingly relate to individuals who have not worked at the company for years, rather than current employees. Enthusiasm from company management to run them is gone. For many, the end game is to secure members’ benefits with an insurance company, in what’s called a “buyout”. This is only achievable once a scheme’s funding has moved from deficit to fully funded (or where a cheque is written to cover any shortfall).

And insurance companies use bond yields to value the liabilities and work out the price to be paid. If you’re targeting a buyout, you can’t dodge them forever.

But what if a pension scheme is to be run on a self-sufficiency basis (where it can pay all pensions without the need for any additional contributions) rather than seek a buyout? Then you can start to argue for a somewhat weaker link with government bond yields and less money invested in bonds. But a DB pension is ultimately a series of fixed and inflation-linked payments to scheme members. The “least risky” asset to back these payments, therefore, is a combination of fixed and inflation-linked government bonds; anything else involves risk. We shouldn’t forget that liability management techniques (buying bonds) have enabled many pension funds to navigate a path to better funding in a much smoother manner than would have been possible otherwise.

Tweaks will do naught

What if valuation methodologies were changed, would it lead to more equities being bought? It’s very unlikely.

Most schemes are closed to new members and have become a liability on a balance sheet to be managed. If an investment decision doesn’t pay off, the sponsor, usually an employer, has to stump up extra cash to pay people’s pensions. For some companies, the pension fund can be quite large relative to the underlying business. If they can’t find the cash or the business goes insolvent for any other reason, the pension fund ends up in the Pension Protection Fund, the industry lifeboat. Once there, members’ benefits are cut.

Investment risk isn’t to be taken lightly – precisely why The Pensions Regulator says the strength of the employer should be taken into account when setting investment strategy. Even if companies were encouraged to invest more in equities, most probably wouldn’t want to.

The counter-example would be a pension fund with a strong sponsor, who is comfortable taking risk and potentially being on the hook to write some cheques if things don’t turn out right. That’s a perfectly reasonable strategy, and one that some pension funds do follow already. The current regulatory regime doesn’t prevent it. But it’s not one that would work for everyone.

Why would a fully funded pension scheme take more risk than it needs to?

Last year’s rise in bond yields has changed pension scheme funding levels dramatically. There are different ways to value pension liabilities, but it doesn’t matter which you use, they all say the same thing: funding levels (assets divided by liabilities) have soared. Assets fell but liabilities fell by more.

According to PwC, UK DB assets are now worth £160 billion more than the value of their liabilities when those liabilities are valued on the stringent, buyout basis. That doesn’t mean every scheme is so fortunate, but many are. And those that are not are a lot closer than they expected to be right now.

The vast majority now have less need to take risk with their investments. So why on earth would they want to jeopardise that by taking a punt on equity markets? There simply isn’t any need.

So, no, even if the funding rules were twiddled with, anyone who is arguing that UK DB will ever be big buyers of UK equities again is living in the past. That ship sailed long ago.

The DB king is dead, long live the DC king

As of March 2022 there were an estimated 960,000 active members of private sector DB schemes. In comparison, thanks to auto-enrolment, there are 18 million active members of DC schemes.

Private sector DC contributions are already more than double the amount going into private sector DB each year. According to data from Broadridge, £49 billion was contributed to DC in 2020, a figure that is rising every year. £25 billion went into private sector DB in the most recently available 12-month period (to June 2022), a figure that is falling every year.

Collectively, £670 billion is forecast to be contributed to DC in the ten years to 2030, taking DC assets to £1.3 trillion from around £545 billion today. Private sector DB assets today are around £1.5 trillion.

This DC projection does not include an estimated £0.3 trillion relating to individuals who are expected to retire during this period, so the true figure which ends up in DC-related retirement savings strategies of some sort will be even higher.

So, if you want to talk about the future of pension funds, DC is where it’s at. And guess what? They allocate lots to equities. Industry assets are dominated by master trusts, vehicles in which individuals spread across many employers can save for retirement. NEST is probably the most well known. According to the Pensions Policy Institute’s DC Asset Allocation Survey, master trust default strategies allocate 70% to equities, for members 20 years away from retirement. And 96% of members end up in the default strategy. So, most contributions end up in equities.

DC pension savers are set to invest many billions of pounds in UK equities in the coming years. Any headwind from DB selling could be about to turn into a tailwind from DC buying.

Unlocking private capital

Many DC savers have several decades until retirement, but most DC savings vehicles have historically only been in funds which can be bought or sold on a daily basis. This has constrained them to assets such as public equities or bonds. They have largely struggled to gain much exposure to private assets, such as infrastructure, private equity, or real estate. The 2020 Pension charges survey found that two thirds of DC schemes had no direct exposure to assets like these.

As a result, DC savers have faced barriers to accessing the appealing risk/reward characteristics which private assets can offer, and private companies and projects have been starved of access to the long-term capital that is growing rapidly in DC pensions.

This has long been acknowledged as a shortcoming. To counter it, the Chancellor of the Exchequer committed in November 2020 to the launch of Long-Term Asset Funds (LTAFs). These new investment vehicles make it easier for a broader range of investors to gain exposure to private assets. They offer periodic liquidity rather than daily. We welcome this development and Schroders recently received approval from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) to launch the first LTAF.

But this alone is not enough. There are close to 27,000 DC schemes in the UK, 25,700 of which are micro schemes of fewer than 12 members. Master trusts are bigger but the 36 we have in the UK also makes this a fragmented market by international standards.

Smaller schemes and master trusts lack the resources, expertise, and scale to invest in private assets in an efficient way. As a result, most do not. We have strongly argued, most recently via the Capital Markets Industry Taskforce, that consolidation is imperative. Without this, it is DC savers that stand to lose out.

But remember, every pound that goes into private assets is a pound that hasn’t gone into UK equities or the government’s coffers. You can’t whack all the moles at once.

So yes, we need to make sure that pensions are regulated appropriately. But always with the appropriate goal in mind: for DB this is maximising the potential for member benefits to be met, and for DC is it maximising the potential for individuals’ retirement needs to be met.

A version of this article appeared first on FT Alphaville