While the world’s attention is on Ukraine, and on climate change, Europe is deindustrialising at a worrying rate.

This is a big problem. Europe might not have great technology companies, fancy services companies, or raw materials. But it has always been good at industry. Even as other rich countries’ industries moved abroad, Europe (particularly Germany) managed to keep hold of theirs by moving up the value chain. So what’s happening?

Industry needs lots of energy. The energy must be cheap, dependable and capable of generating a lot of heat. Industry needs heat because lots of industrial processes rely on intense heat — like blast furnaces used to make steel.

Europe’s industrial heartland is Germany. It has the big automotive, chemical and metallurgical companies. The big companies generate an ecosystem of thousands of small suppliers.

Volkswagen makes nine million cars per year. It is surrounded by small specialised suppliers, each making a couple of hundred precision tools per year. In Eastern Europe, most countries’ biggest industry is supplying automotive parts for the German auto industry.

German industry is shrinking. It’s shrinking not because there is less demand for Volkswagens, or because the government there decided to tax it more heavily — but because it can’t get the energy it needs.

On a visit to Dublin on Tuesday, German Minister of Finance Christian Lindner was asked about the ongoing debate in his country as to whether it has become “the sick man of Europe” in economic terms. “Germany is not a sick man but we have a problem with our fitness,” Lindner said. He pointed to the need for labour market reform, easier application of funds from EU-wide capital markets to invest in SMEs and German corporation tax reform. With this, “the unfit will be fit again,” he assured.

Industrial sectors, however, are facing a specific energy challenge. In 2011, Germany decided to shut down its nuclear power plants. It did this because nuclear energy is broadly unpopular. The nuclear plants were due to be gradually powered down between 2011 and April 2023.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine. This posed a big problem for German industry. Germany’s industrial machine depended on cheap, reliable and heat-generating natural gas from Russia. In the supply crunch that followed the invasion, everyone worried that Europeans would freeze in the winter of 2022/23. Industry was expected to dramatically cut its energy consumption.

In 2022, European chemical production was cut by five per cent. Aluminium production was cut by 12 per cent. Steel was cut 10 per cent. Paper was cut by six per cent. Having fallen 5.8 per cent in 2022, electricity consumption continued to fall in 2023, by six per cent, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The following year, production continued to fall by similar amounts. Chemical production, for example, fell a further 18 per cent. The IEA said: “Some permanent electricity demand destruction has already occurred, especially in energy-intensive chemical and primary metal industries, and there is still significant uncertainty about how much of the reductions of the last two years will be temporary or permanent.”

When the tanks rolled into Ukraine, why did Germany not turn its nuclear plants back on? Part of the answer was that German leadership dithered. Another part is that it’s not easy to spin up a nuclear power plant. It’s not like a tumble dryer.

Now, European industry has a similar problem. Once production is shut down, and companies move production elsewhere, it’s hard to get it back.

Industry is capital-intensive. It’s hard to get going. But once you get the initial investments out of the way, it’s profitable. Europe’s energy squeeze pushed a lot of industrial companies to make those investments but then move offshore. Tara Mines, which has been mothballed since last summer, is the highest-profile Irish example, but there are hundreds across Europe. Last month, Tata Steel announced it was closing its blast furnace in Port Talbot, Wales, with the loss of up to 2,800 jobs.

Just as all this was happening, the Biden administration passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA is a huge budget package that includes $500 billion (€463 billion) worth of subsidies for industry. Energy shortages and high prices pushed industry away from Europe right at the moment that the IRA pulled it towards the US.

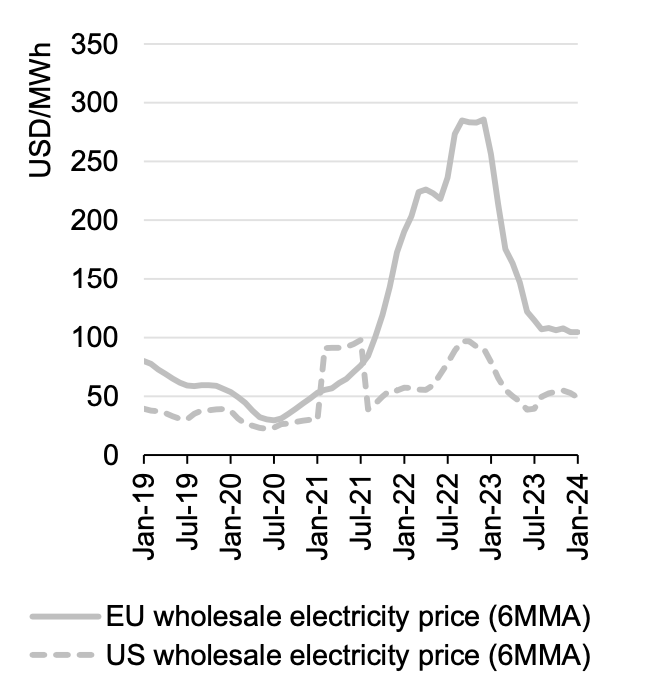

The US offers a combination of attractive subsidies, a strong domestic market and cheap abundant energy. It’s a good offer to European industrials. The following chart shows how US electricity prices compare to European ones.

The trend is clear when comparing American to German industrial output.

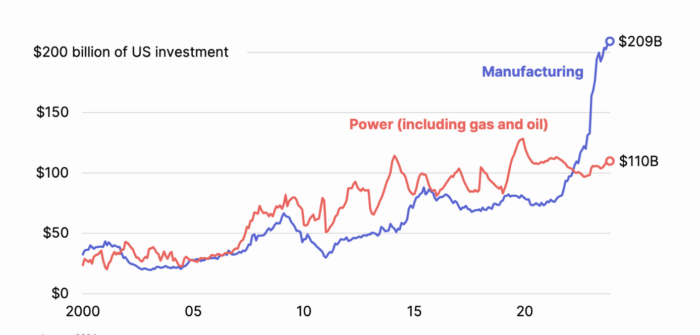

More is yet to come. As the following chart from Nat Bullard’s excellent annual presentation shows, investment in American manufacturing has more than doubled in recent years.

In a dynamic economy, businesses and sectors rise and fall all the time. That’s normal. Most of the time the changes happen without anyone noticing.

The decline of industry is not like this. Because the firms are so large, the decline of a big industry can bring ruin to their region. Places like Gary, Indiana or Sunderland in the northeast of England show the effects. The land, capital and labour that are used for industry can’t pivot towards the next thing. The workers’ skills are specific. The land is contaminated. The machines and buildings are only useful for the purpose they were designed.

Except for a few companies like Tara Mines or Aughinish Alumina, there isn’t much heavy industry in Ireland. That leaves us less exposed. But Ireland’s “domestic market” is that of the EU. A shrinking EU does us no good.

What I’m describing is a deep rewiring of the European economy. It’s something that is happening quickly. And it’s not happening deliberately. Because of bad luck, bad decisions (Germany dropped the ball twice, in its reliance on Russia and shutting down its nuclear power) and strong competition from the US, Europe has a big problem.

When industry leaves, it tends not to come back. Europe’s energy policy, meanwhile, is focused on the diametrically opposite problem, which is reducing carbon emissions. The current approach is not working, that’s for sure.