Editors’ Note: MarketMinder Europe’s commentary is intentionally nonpartisan. We favour no politician nor any party and assess developments for their potential economic and financial market impact only.

Is a new financial crisis coming home to roost? Global headlines we saw zeroed in on spiking long-term Gilt yields Wednesday, noting multi-decade highs in some maturities.[i] This coincided with the Conservatives’ party conference, where Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt poured cold water on expectations for tax cuts and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak cancelled HS2’s northern leg. Alongside the widely reported budgetary problems in Birmingham and other local councils, these developments spurred some commentators we follow to warn high borrowing costs are forcing the UK into austerity, if not a financial crisis. In our view, this seems far too hasty. Gilt yields’ move is part of what we think is a sentiment-fuelled global move. Bond markets endure these sharp selloffs now and then, and they frequently end quickly.

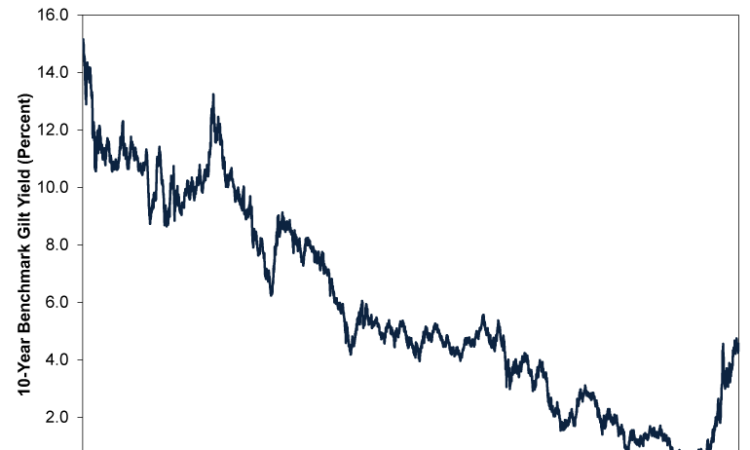

Borrowing costs are indeed up, as we have explored in recent commentary, and yields’ recent jump was swift. Yet in our view, some historical perspective is in order. As Exhibit 1 shows, 10-year Gilt yields have endured similarly sized jumps before, then quickly reversed. It shows this isn’t the first time Gilt markets (or indeed bond markets globally) have sold off quickly, and it likely won’t be the last. Importantly, too, even with the jump, today’s yields are on par with yields in the mid-2000s and well below levels seen for much of the 1990s. If those weren’t tough times of a stagnant economy and deep austerity, we don’t think rates’ latest jump renders these dismal outcomes automatic.[ii]

Exhibit 1: Yields’ Latest Rise in Historical Perspective

Source: FactSet, as of 4/10/2023. UK Benchmark 10-Year Gilt Yield, 31/12/1981 – 3/10/2023.

That so many commentators we follow are hyping yields at multi-decade highs says more about how low yields have been this century than anything else, in our view. It seems like a psychological phenomenon called recency bias at work: People anchor to what just happened, rendering anything outside of that a shock even if it was the norm over the entire history. We find a measured view of history is usually a good antidote.

Another thing you will see in the chart: Bonds don’t move in straight lines. They wiggle. Their expected short-term volatility may be milder than stocks’, but bonds have their moments—their fair share of sharp moves that don’t last.[iii] We think this is likely to be the case today, and everything comes into focus—including why sentiment is so bad now—when you factor in a general premise that bond markets are forward-looking, which our research finds to be the case.

After reading a range of coverage this week, we have gleaned that the main source of today’s warnings seems to be that bond yields aren’t behaving as one would expect during periods of easing inflation. All else equal, conventional wisdom holds that bond yields reflect inflation expectations over the bond’s maturity, with higher inflation usually bringing higher yields to compensate for the bond principal’s eroded purchasing power. Falling inflation, at least in theory, brings falling yields. For the past several months, however, several countries including the UK and US have had falling inflation and rising yields. What gives? Simply, we think bonds pre-priced inflation improvement late last year and earlier this year. In our view, markets saw the signs of it in the emerging data, anticipated further improvement, reflected that in prices, and then moved on. The inflation data across North America and Europe—and inflation’s leading indicators—appeared to us to be too widely known for there to be much (if any) positive surprise power left by the springtime. It got pre-priced, at least in part, in our view.

Meanwhile, with economic fundamentals in the UK, US and other nations holding up much better than many forecasters including the Federal Reserve (Fed) and Bank of England (BoE) projected, we think there was little to no reason for recession risk to pull long yields lower. Improving economic conditions also pointed to a deeply inverted yield curve that wanted to steepen, which would either mean falling short rates or rising long rates. (The yield curve is a graphical representation of a single bond issuer’s interest rates across the spectrum of maturities, and it is inverted when short-term rates exceed long-term rates.) Continued BoE and Fed hikes precluded the former for the time being, making it likelier than not that long rates would rise somewhat as this year wore on. In our view, this probably explains a lot of long rates’ slow rise since the spring, in the UK, US and Continental Europe.[iv]

But the magnitude of the recent move seems exaggerated by sentiment, in our view. Fundamentals haven’t changed, broadly. Yes, there is a lot of talk about rising bond supply as several nations run budget deficits, but this is a well-known factor. If the incessant headline coverage is any indication, we think it is fair to presume investors have chewed over government bond issuance plans in the US, UK and rest of the developed world for months, and the latest auctions confirm the market is having little trouble absorbing it.[v] The Fed and BoE’s balance sheet reduction plans are also well-telegraphed, which we think enabled markets to discount them in advance. In our view, higher borrowing needs don’t explain the latest spike.

Absent major fundamental supply and demand shifts, there is a lot of chatter on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Whilst it may seem strange for events in America to affect UK bond yields, our research finds bond markets globally tend to be tightly correlated, making it sensible to monitor sentiment in US fixed income markets.[vi] There, headlines are buzzing over the House of Representatives’ unprecedented vote to oust now-former Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy. Until lawmakers agree on a replacement, it brings the chamber’s official business to a halt.

Given McCarthy reportedly had a difficult time securing the necessary support to win the Speakership in the closely divided House in January, American political analysts warn the replacement contest could drag out and interfere with budget negotiations, potentially running up against November’s deadline to avoid a partial government shutdown (in which non-essential government services would close temporarily, furloughing workers until a new funding deal is in place). Several commentators we follow tied this to a selloff in US Treasury bonds. It doesn’t shock us that this would hit sentiment, but we don’t see a fundamental connection. Political gridlock in the House isn’t new, and we think shutdowns have next to nothing to do with the US government’s creditworthiness, no matter what credit-raters like Moody’s claim.[vii] Our research also finds shutdowns haven’t historically caused bear markets or recessions.[viii] So yields’ jump seems like a classic overreaction to us.

As for UK-specific factors, we have seen headlines globally dwell on the handful of UK councils issuing Section 114 notices. Some coverage reports this as bankruptcy notices, speculating that the Treasury will have to bail out the local authorities, potentially requiring even higher central government deficits and spurring national austerity as a result. We think this is wide of the mark, and a House of Commons Library publication sheds some helpful light. It states plainly that “UK local authorities cannot go bankrupt,” and the Section 114 notices are simply formal notices that the council’s income will fall short of the next year’s projected expenses. The typical solution, according to the Commons, is spending cuts. Occasionally, councils will seek government permission to sell assets to meet the shortfall, or the central government will “intervene in how council services are run,” which the publication explains generally amounts to cutting services. Outside a handful of small grants to support essential social services, central government funds aren’t involved.[ix] So we think the image of HM Treasury borrowing bigtime to bail out councils and creating a sovereign debt crisis seems far-fetched.

When reviewing market history, we find bond market volatility—like stock market volatility—often ends as quickly as it begins.[x] The sharp moves can be painful, but we find staying cool is generally the wisest move, and we think it is wise today. It might be unrealistic to expect yields to get back to their springtime lows, given what we view as fundamental reasons for yields to have drifted higher over the summer, but they don’t seem likely to us to keep soaring from here.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 4/10/2023. Statement based on benchmark 10- and 30-year UK Gilt yields.

[ii] Ibid. Statement based on UK gross domestic product (GDP). GDP is a government-produced measure of economic output.

[iii] Source: FactSet and Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 4/10/2023. Statement based on the standard deviation of stock and bond returns over rolling one-year periods. The standard deviation is a statistical measurement of how much returns deviate from their average.

[iv] Ibid. Statement based on benchmark 10-year government bond yields.

[v] Source: UK Debt Management Office and US Treasury, as of 4/10/2023.

[vi] Source: FactSet, as of 4/10/2023. Statement based on the correlation coefficient between US and UK 10-year benchmark government bond yields. The correlation coefficient is a statistical measurement of the directional relationship between two variables. A correlation of -1.00 implies they always move in opposite directions, 0.00 implies no relationship and 1.00 implies they always move in lockstep.

[vii] “Moody’s: Government Shutdown Could Hurt America’s Top Credit Rating,” Alicia Wallace, CNN, 25/9/2023.

[viii] Source: FactSet, as of 4/10/2023. Statement based on S&P 500 price returns in USD and US GDP growth rates surrounding US government shutdowns. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.

[ix] “What Happens If a Council Goes Bankrupt?” Mark Sandford, House of Commons Library, 13/9/2023.

[x] Source: FactSet, as of 4/10/2023. Statement based on S&P 500 price returns in USD, MSCI UK Investible Market Index returns in GBP, MSCI World Index returns in GBP and benchmark government bond yields in the US, UK, Germany and France. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.