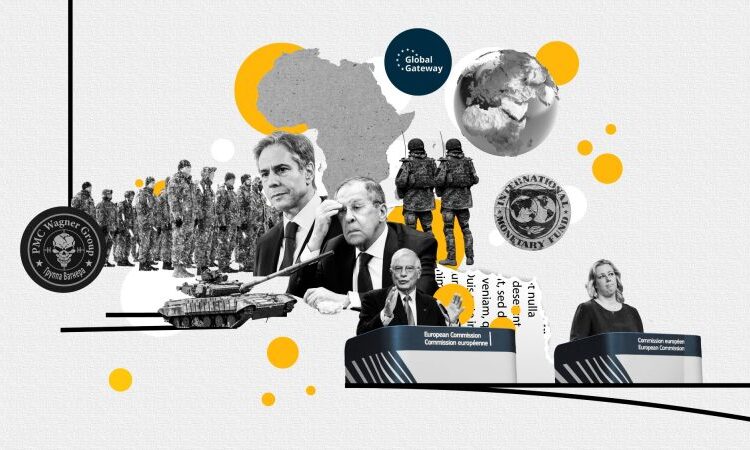

Russia’s growing influence across Africa over the past decade, laid bare by Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, has sparked significant concern, leaving Europeans struggling to find ways to counter it.

If China measures its influence across Africa through the volume of infrastructure investment, the EU is trying to build a broad political and economic relationship based on trade, investment, aid and technical support from Brussels in exchange for African states doing more to control irregular migration.

Russia’s strategy in Africa, meanwhile, so far has involved a mix of arms sales, political support to its authoritarian leaders and security collaboration at the expense of French influence in the Sahel region and central Africa, typically in exchange for business opportunities and diplomatic support for Russia’s foreign policy preferences.

After four years of neglect under the Trump administration, meanwhile, his successor Joe Biden has begun the process of rebuilding the United States’ influence in Africa.

‘Shuttle diplomacy’

Moscow’s relative popularity in the Global South continues to frustrate observers in the West.

Most recently, weeks where a visit by Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov is followed or preceded by high-ranking EU or US administration officials, have become commonplace.

On his first swing through the continent in January, Lavrov visited South Africa, Eswatini, Angola and Eritrea. In a second leg in February, he stopped by Mali, Iraq, Sudan and Mauritania to shore up support for Russia in Africa.

Russia has long used “memory diplomacy” in Africa, but after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, these tactics have really started to pay off.

“Russia tries to market itself as an anti-colonial power to Africans, with a huge touch of victim mentality towards the West, which seems to strike many sentiments in the region,” a frustrated EU official admitted.

“What many countries in the region fail to acknowledge, is that Moscow itself has not been falling short of brutal colonialism in its neighbourhood,” the EU official added.

South Africa, meanwhile, has become the most vivid example of the West vying for influence over Russia’s charm offensive on the continent.

“Russia was among the few world powers that neither had colonies in Africa or elsewhere nor participated in [the] slave trade throughout its history. Russia helped, in every possible way, the peoples of the African continent to attain their freedom and sovereignty,” Russia’s embassy in Pretoria tweeted last year, sparking anger in Europe and the United States.

In the span of a few days, Lavrov and US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen as well as the EU’s chief diplomat Josep Borrell paid a visit to the country.

Pretoria has strong historic ties with Moscow dating back to Russia’s support of the African National Congress during the apartheid era and has taken an officially neutral stance on the conflict, to the dismay of Washington and Brussels.

“I very much hope that South Africa, our strategic partner, will use its good relations with Russia and the role it plays in the BRICS group to convince Russia to stop this senseless war,” Borrell then said speaking alongside Pretoria’s Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor.

Earlier, Pandor gave Lavrov a warmer welcome.

Asked by a reporter whether she would repeat the call made by her ministry early last year for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine, she said she would not, noting the massive transfer of arms to Ukraine that had since occurred.

What followed were much-criticized military exercises with China and Russia the month after, to which the EU side responded that Pretoria has the right to follow its own foreign policy, but noted the drills were not what the bloc “would have preferred.”

Disinformation and food propaganda

Beyond the diplomatic battle, comes another one.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly accused the West of being responsible for disrupting the global supply chains – something that has hit African states, which are particularly reliant on wheat and grain imports, harder than most.

The International Monetary Fund has reported that staple food prices in sub-Saharan Africa increased by an average of 23.9% between 2020 and 2022.

EU leaders had appealed to African countries not to fall for a Russia-led propaganda campaign that portrayed the current global food insecurity caused by a disruption to the global supply of grains and fertiliser as the result of Western sanctions against Moscow.

Experts believe a key reason why some pro-Russia disinformation narratives about the war in Ukraine have found resonance, especially in Africa and Southeast Asia is that they have successfully tapped into pre-existing anti-US and anti-West sentiments.

EU officials have called for a more proactive approach to disinformation and propaganda, but so far the bloc has had limited resources to deal with the matter.

“You have to present your truths, and you have to have a plan, and you have to counterattack, because the Russians, very much equalled by the Chinese, are doing that in a very much well-organized manner, as a real battle,” a senior EU official described the bloc’s efforts last summer.

“The global battle of narratives is in full swing and, for now, we are not winning,” EU’s chief diplomat Josep Borrell admitted shortly after.

But the narrative sticks – and is evolving.

Most recently, the EU said it will launch a new platform to counter disinformation campaigns by Russia and China.

Beyond the platform, Borrell also announced he plans to strengthen EU delegations abroad with disinformation experts “so that our voice can be heard better”, in “a long-term battle” that “will not be won overnight”.

“This is one of the battles of our time and this battle must be won,” Borrell stated.

EU missions and operations are increasing “targets” of disinformation and manipulation of information by foreign actors, while EU delegations “face an increased risk of becoming a target of these initiatives, with potential threats putting staff at risk”, a senior EU official told reporters recently.

However, there are indications that African leaders are increasingly resistant to Western diplomatic attempts to target Russia.

African Union chair Macky Sall has expressed concern about the Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act, a bill which has Wagner’s activities in its crosshairs, currently on the table in the US Senate, arguing that this could lead to sanctions against African firms doing business with Russian counterparts.

Wagner looming

The shadow of Russian influence also hangs over the EU’s embattled diplomatic and security agenda in the Sahel.

One mentioned by the EU source is the bloc’s training mission in the Central African Republic, where reports that EU instructors might have provided training to local forces controlled by the Russian mercenary group, Wagner, sparked concerns about Moscow’s increased destabilising influence in the region.

The EU has recently launched programmes aimed at tackling what the European Commission describes as Russian ‘disinformation’ on social media in the Sahel.

Officials in Brussels are also keenly aware that Russia wants to expand its presence via the Wagner group in the region, but it is less clear whether they can do anything to stop it.

Military regimes in Mali and Burkina Faso have stepped up their diplomatic contacts with Russia, and it is likely that Chad, Niger, and other countries in the Sahel and neighbouring regions will also be targeted by the Kremlin.

Investment and doubt

In the coming months, the EU is likely to offer financial inducements – potentially several billion euros – primarily to North African states, for migration control after the bloc’s leaders doubled down on the need to increase repatriations and tackle irregular border crossings at their own summit in Brussels last month.

At a meeting between the European Commission and African Union in November, the two sides agreed that the EU would start to allocate funds for infrastructure investment from its ‘Global Gateway’ programme and provide support for an African Medicines Agency (EMA), alongside the creation of a ‘high-level dialogue on economic integration with a view to strengthening trade relations and sustainable investment.’

The EU’s Global Gateway scheme, intended to be the bloc’s answer to China’s Belt and Road initiative, will start paying out €750 million in infrastructure funding to African states over the coming year.

However, these are small sums compared to the Chinese or US offers – the Biden government has promised to invest at least $55 billion in Africa over the next three years and wants to increase bilateral trade with Africa via the tariff and quota-free trade offered by its Africa Growth and Opportunity Act – and African diplomats regularly complain that accessing EU funding involves more bureaucratic hurdles.

Where Russia is out of step with its international rivals is on the EU and Chinese-led campaign for the African Union to have a seat at the G20, while the US and Europe also support an African permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.

In the meantime, however, the reality is that Moscow has managed to acquire more political leverage in Africa than its economic and diplomatic investment suggests it should. For most of the last decade, EU officials have been increasingly frustrated by China’s growing economic influence in sub-Saharan Africa. There is now growing reason for them to cast their eyes nervously to the east.