Europe must invest heavily in its decarbonisation. Yet the expenditures are manageable and the alternatives unconscionable.

All European Union member states have pledged to decarbonise their economies by 2050, aiming for net carbon neutrality. This ambitious goal requires ensuring that, by mid-century, Europe’s greenhouse-gas emissions do not exceed what its carbon sinks, such as forests, can absorb.

Given the EU’s historical responsibility, its contemporary emissions and its global influence—the second biggest regional market for most manufactured products—upholding this commitment is essential to secure a liveable future for the next generation. Yet some are challenging these climate commitments, arguing they are too expensive, punitive to economic actors, technically infeasible or overshadowed by urgent crises such as the conflict in Ukraine.

Achievable and affordable

These arguments are flawed, as evidenced by the report ‘Road to Net Zero’ from the Institut Rousseau. Presented to the European Parliament at the end of last month, the report charts a physically achievable and financially affordable path to decarbonisation, for the entire EU, by 2050. It was crafted with input from more than 150 researchers, engineers, economists and public-policy experts across Europe.

The good news is that, given adequate efforts, the EU-27 can slash emissions by 85 per cent within a generation, achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. Nor does this spell doom for the European economy—quite the opposite.

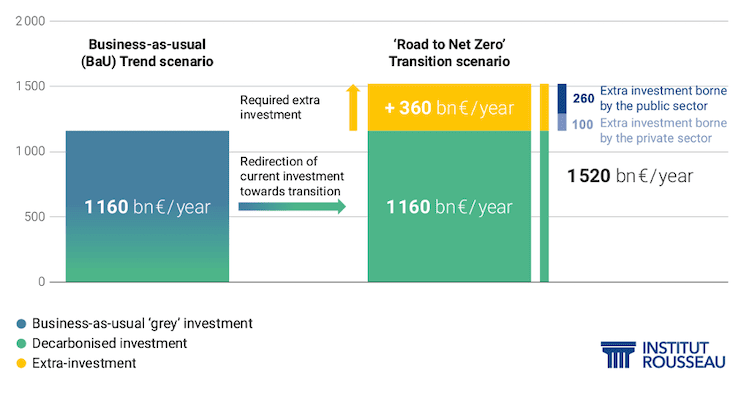

Three-quarters of the necessary funds (Figure 1) already exist and must be redirected—for instance, from diesel cars towards public transport and low-carbon vehicles. An additional €360 billion or so would be needed annually, 2.3 per cent of European gross domestic product. Europe spent twice that in 2022 on fossil-fuel imports which wreak havoc on our environment. It is not the transition that is costly but Europe’s collective failure to plan for the phase-out of fossil fuels.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Figure 1: total investments and additional investments (billions of euro) per year, compared with ‘business as usual’, required to achieve carbon neutrality in the EU-27 by 2050

A report from the European Commission issued this month confirmed these global investment figures (€1,531 billion per year), though there are variations across sectors. The commission’s plan involves higher investments in road transport and energy, reflecting a lower ambition on reduction of fuel consumption. However, it lacks substantial provisions for agriculture and is less ambitious on building renovation, compared with the Institut Rousseau.

The added value of the institute’s plan also lies in isolating public investment within the total required. It proposes more than 70 public-policy measures, inspired by successful strategies in leading European regions—such as organic farming in central Italy, rail transport in Austria and cycling infrastructure in Denmark. Public expenditures must double, reaching €510 billion annually. Of the additional €360 billion needed yearly, compared with the status quo, €260 billion must come from the public purse.

This level of public investment is vital for two reasons. First, about 25 per cent of the required public investment is direct expenditure on public transport, renovation of public buildings and so on. The rest is needed to lever private investment by supporting various actors in the transition, unlocking essential private funds. This is crucial for the success of the European Green Deal and the challenge is well illustrated by the farmers’ legitimate discontent over falling incomes. European economic actors need not only financial support but also protection from unfair external competition.

Self-destructive limit

This work underscores the inseparable link between the transition and robust public support. Yet the current regulatory and fiscal framework severely limits states’ flexibility—which, if it does not change, will prove self-destructive.

For instance, regulations on ‘state aids’ significantly curtail public support by prohibiting, except in certain cases, any support for companies capable of distorting competition. The suspension of these regulations under the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework, designed to aid EU member states to emerge from the pandemic and the shock of the war in Ukraine, should be made permanent. Nor is the European economy sufficiently shielded from external socially and environmental undercutting. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) must be strengthened swiftly to protect Europe’s industry and free-trade agreements that significantly disadvantage its farmers should be revisited.

From a fiscal standpoint, the additional €260 billion in annual public investment, amounting to 1.6 per cent of current European GDP, clashes with the 3 per cent public-deficit ceiling in the Stability and Growth Pact, which would be sustained in the revised fiscal rules under negotiation. This contradicts a key objective of the current commission—realising the Green Deal.

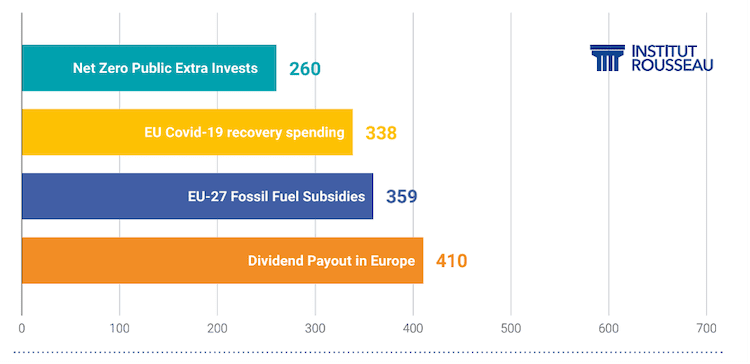

Some may argue that allocating an additional €260 billion per year for EU-wide decarbonisation is excessive. Yet there are four compelling counter-arguments.

Entirely justified

First, these expenditures are entirely justified, compared with the costs of inaction. The business world already understands that climate change poses a significant threat to the economy, with the reinsurance company Swiss Re estimating a business-as-usual average annual GDP loss for Europe of 10.5 per cent by 2050—equivalent to the cost of a war.

Secondly, this investment pales by comparison (Figure 2) with the public expenditure committed to the European post-pandemic recovery plan (€338 billion per year) or current fossil-fuel subsidies (€359 billion per year, including energy price caps). Transitional investments thus merely reallocate existing public subsidies, which will diminish gradually as the economy decarbonises.

Figure 2: annual additional public investment in the EU for net zero by 2050, with various comparators (billions of euro)

Thirdly, public expenditures will stimulate economic activity, generate millions of net local jobs, enhance European competitiveness and resilience amid global crises and bolster purchasing power in the short term. As Mariana Mazzucato points out, without public investment economies falter. After a decade of counterproductive austerity, Europe has missed the boat on new technologies—China has emerged as a leader in batteries, wind, solar and electric transport. While Europe talks about slowing its climate action, the US Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 has mobilised around $400 billion to support decarbonised industries. India has initiated Production-Linked Incentive schemes and China is subsidising its industries at various government levels, with fiscal and monetary levers.

Finally, this public investment will yield long-term savings and alleviate future pressure on public budgets. This will come through reductions in direct operational expenditures (energy consumption by public buildings, maintenance of rail and road infrastructure and so on), as well as in spending on unemployment insurance and adaptation to climate change.

More pronounced

All these benefits will be even more pronounced as local production is prioritised and consumption reduced.Electrification of energy without a simultaneous reduction in demand not only incurs higher costs, such as an additional €200 billion per year in alternative fuel imports in scenarios with less reduction of consumption. It also poses greater risks to energy sovereignty, due to resource constraints and challenges of industrial deployment.

The Road to Net Zero scenario is not tailored for blind ideologues who believe in solving climate challenges while cutting investments. It is a comprehensive transition plan crafted for pragmatic decision-makers and citizens seeking tangible action over empty rhetoric. Austerity, as seen tragically in Lebanon today, only leads to collapse. Failing to fund the ecological shift will ultimately prove far costlier. Each year of inaction escalates the bill. Conversely, every step toward sufficiency, rather than endless growth, and local production reduces it.

Embracing ecological transition is not just an environmental imperative. It is a strategically rational and economically advantageous choice for Europe. Will Europe rise to the occasion and meet the demands of history—or will it remain shackled by outdated dogmas?

This is included in our series on a progressive ‘manifesto’ for the 2024 European Parliament elections