Welcome to Foreign Policy’s China Brief.

The highlights this week: The White House’s new restrictions on U.S. investments in China show there’s no end in sight for the U.S.-China tech wars, Beijing extends a conciliatory hand in a maritime dispute with Manila, and another major Chinese property developer raises alarm in the real-estate sector.

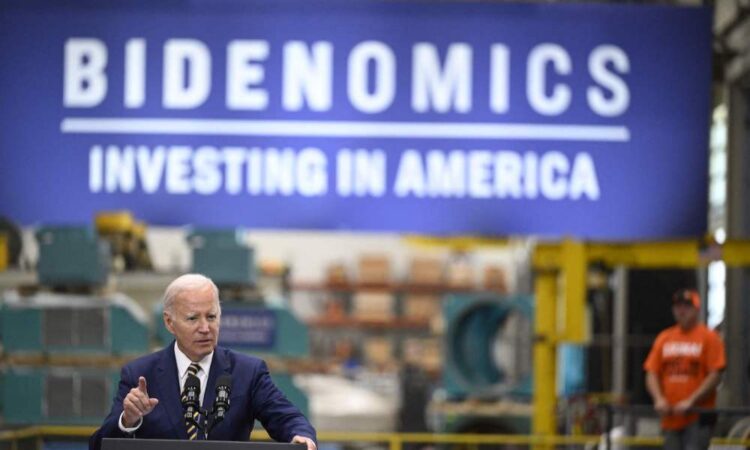

U.S. President Joe Biden set new limits on U.S. investments in China last Wednesday, focusing on key technology sectors including advanced chipmaking, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing. Of these, chipmaking is already a major front in the U.S.-China tech wars. AI is an obsession of Beijing’s, which has produced a ton of projects, although few with practical purpose; quantum computing and communications have powerful potential.

Biden’s executive order restricts the sharing of key technological information linked to investment deals and blocks investment in companies that research and develop these technologies. It does not just cut off funding to China, where, as one administration official put it, “they have plenty of money.” The limits also tie in with Biden’s focus on a revived U.S. industrial policy. But officials in Beijing will read the rules as another sign of Washington’s determination to cut China off from the world—reinforcing the idea that China must develop its own alternatives.

China has moved toward self-reliance under President Xi Jinping anyway, with a constant emphasis on domestic production and detachment from global supply chains. This reflects a rubber-band effect: The spate of measures under former U.S. President Donald Trump and now Biden seem more severe because the United States took a lax approach to technological transfer and sensitive investments in China for decades. To some degree, U.S. economic policy has caught up with what U.S. security and intelligence officials have wanted for a long time.

Just how the United States will implement the new measures is still unclear, but they have already dealt a blow to some Chinese tech firms, particularly those working on artificial intelligence. Investors are scrambling to work out exactly what the restrictions will mean for them. Some lobbyists in Washington have pushed back against the tech rules. Meanwhile, China is doubling down on anti-foreign sentiment and restrictive tech policy itself.

It’s hard to see any chance of de-escalation in the U.S.-China tech wars, to the distress of those caught in between, such as Singapore. In the United States, where China is deeply disliked, measures to restrict trade with China are broadly popular—even if they have a hard time moving through a perpetually divided Congress. Republican politicians object to Biden’s measures on the grounds that they either don’t go far enough or aren’t friendly enough to U.S. business, depending on who one talks to.

Critically, many investors are ahead of the Biden administration. Foreign direct investment in China has reached a 25-year low. (And in 1998, China’s economy was a fraction of its current size.) Three concerns have driven that decline: fears about the Chinese economy, Chinese measures targeted at foreign firms and the political risks to foreign staff, and restrictions imposed by the United States. But that last factor is probably the least important, simply because Washington is far more predictable and open than China about business-related actions.

China has sought to reassure foreign firms, but it’s hard to hold out a welcome with one hand while sticking a finger up to the world with the other. Under Xi, Beijing’s overwhelming concern is national security; in any conflict between the securocrats and the economists, the securocrats will win every time. Combine that with the seismic shocks to the Chinese economy this year—from bad debt to rising unemployment—and it doesn’t take Biden to stop foreign firms from investing. China is doing a pretty good job of it itself.

Philippines dispute. After a Chinese ship fired a water cannon at a Philippine vessel last week, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reached out a conciliatory hand to Manila, saying the two sides should work together to resolve tensions. China and the Philippines have many maritime disputes stemming from China’s extensive claims to islets and shoals in the South China Sea, largely decided in Manila’s favor by a 2016 international court verdict.

In this case, the clash turned around the Second Thomas Shoal, known as Ayungin Shoal by the Philippines and Ren’ai Reef by China. In 1999, the Philippines deliberately grounded a transport ship at the submerged reef to create an outpost, which is staffed by a handful of marines. Chinese vessels tried to block resupply of the outpost in the past, but the situation has deteriorated since what Beijing describes as Manila’s violation of a 2021 agreement, which the Philippines disputes.

Wang’s words may indicate that China doesn’t currently have the stomach for a full-blown conflict with a U.S. treaty ally, although he made sure to blame the United States for supposedly being the “black hand” behind the dispute.

Property group stumbles. Major property developer Country Garden is set to become the latest Evergrande Group after missing two overseas bond payments last week. Country Garden’s owner, Yang Huiyan, was once the richest woman in Asia but has reportedly lost more than $28 billion since 2021; her father, Yang Guoqiang, founded the firm and handed over a majority share to her in 2007. Country Garden is soon expected to post losses of up to $7.6 billion for the first half of 2023, sparking concerns about the company’s viability and potential contagion in an already-vulnerable sector.

At this point, the Chinese government is essentially holding up the real-estate sector, but even Beijing’s considerable power may not be enough to bear the weight of so many stumbling giants. Investors and analysts hoped the worst was over, but the Chinese public simply isn’t spending—even on what was once seen as a perpetually safe bet for investment. Country Garden going under could be the trigger for a wider sector collapse—or it could be just another burden for the state to bear, as Evergrande has become.

Bankers’ wages cut. Chinese state-owned banks are slashing salaries for some bankers by up to 15 percent. The move follows a push from Beijing as part of the “common prosperity” campaign, a Xi-era slogan pushing to reduce visible wealth inequality, as well as raising pay for junior staff. The problem is that Chinese officials, including in state-owned enterprises, are already underpaid. Very generous benefits, from two-hour lunches to the state helping cover mortgage payments, have traditionally compensated for lower salaries, as well as corruption.

This gap is particularly apparent in big financial institutions such as the People’s Bank of China, where the trained personnel could earn much more in the private sector or abroad. Financial regulators faced pay cuts of as much as 50 percent in March, and talent is already departing in droves, according to insiders. That could leave China with less-qualified staff who lack other options as the country faces its biggest financial challenges in decades.

Youth unemployment cover-up. After months of record youth unemployment in China—in June, the figure reached more than 21 percent—the government has stopped publishing the data for the foreseeable future, citing “constantly changing economic/social conditions.” There has been extensive reporting on the youth jobs crisis, and it’s clearly become the kind of embarrassment Beijing prefers to sweep under the rug than fix—keeping with its recent warnings to economists not to be negative.

In China, youth unemployment joins thousands of other data points that are no longer published. Autocratic regimes, especially communist ones, are notorious for bad or incomplete data—not least because unpalatable information can have deadly consequences for those who publish it. In the early 2000s, China made slow but meaningful progress on data transparency, pushed by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). But as Xi’s rule has stretched on, that trend has reversed, with more than half of NBS data disappearing from public view between 2012 and 2016.

Aside from youth unemployment, Beijing may be dealing with dire demographic data from last year. A briefly surfaced report in a state media outlet, now removed, suggests that China may have hit a record-low fertility rate of 1.09.