GOCMEN

Co-produced by Austin Rogers for High Yield Investor

Some value investors in the US have been eyeing Chinese stocks as the performance divergence between US stocks (SPY) and Chinese stocks (MCHI, FXI) continues to widen.

One might think that all of China’s current malaise is already priced in, or that it can’t get any worse for the Chinese economy. Everyone already knows about the bursting of the property bubble, for example.

Meanwhile, Chinese stocks certainly look undervalued. The P/E ratio for the Chinese stock index is about 11.5x, and its trailing twelve month dividend yield is about 3.9%. On the other hand, the S&P 500’s P/E ratio is a little over 21x, while its dividend yield sits at a very low 1.3%.

Should investors follow the example of the late Charlie Munger and go bottom fishing in the Chinese stock market?

We think that is a bad idea.

In what follows, we highlight three reasons why we believe Chinese stocks are “fool’s gold” and why we think value investors should look at high-yielding US stocks instead.

1. China’s Export Growth Has Stalled

Over the past several decades, the Chinese economy has been largely driven by its industrialization and growth in exports. In the latter decades of the 20th century and the first few decades of the 21st century, China became the world’s factory, allowing its developed nation trading partners to shift toward the services sector.

Since peaking around the turn of the calendar from 2021 to 2022, total Chinese exports have stalled.

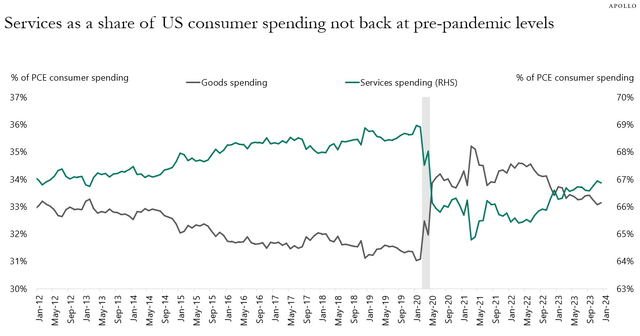

Rather than a continuation of pre-COVID growth in exports, this post-COVID surge in Chinese exports should be seen as a temporary shift in developed economies from services spending to goods consumption.

That temporary reversal of previous trends in services and goods spending (as a share of GDP) has since been rebounding back to pre-COVID levels.

The Daily Spark

Thus, the current situation should probably be seen as a return to the pre-COVID stagnation in Chinese exports as developed nations around the world turn to “nearshoring” and “friendshoring.”

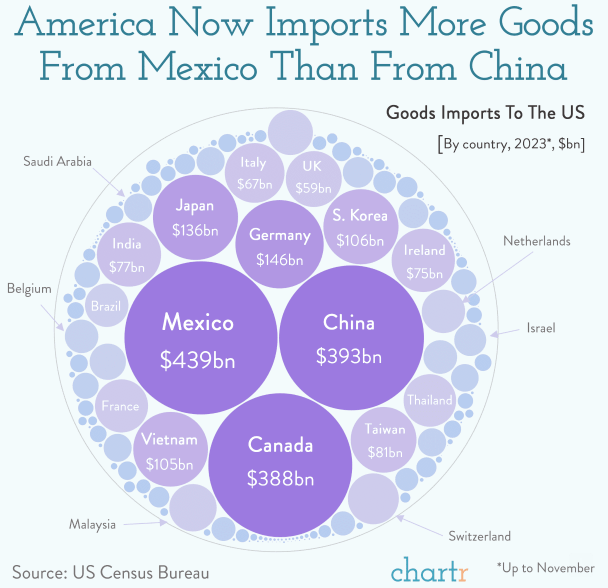

Notably, in 2023, China lost its spot as the largest source of imports into the United States to Mexico, and Canada was close on China’s heels as of 2023.

Chartr

However, if you look at the last few months of 2023 and initial months of 2024, you will find that imports from Canada have recently outpaced Chinese imports as well.

This could result in China being knocked down to the third largest source of US imports in 2024.

While China would certainly like to transition away from its longstanding status as a manufacturing economy to more of a services economy, it faces an uphill battle in making this transition successfully.

As such, stagnating exports will almost certainly have negative ripple effects on the Chinese economy that will ultimately filter into the performance of Chinese stocks.

2. China’s Population Will Shrink Indefinitely

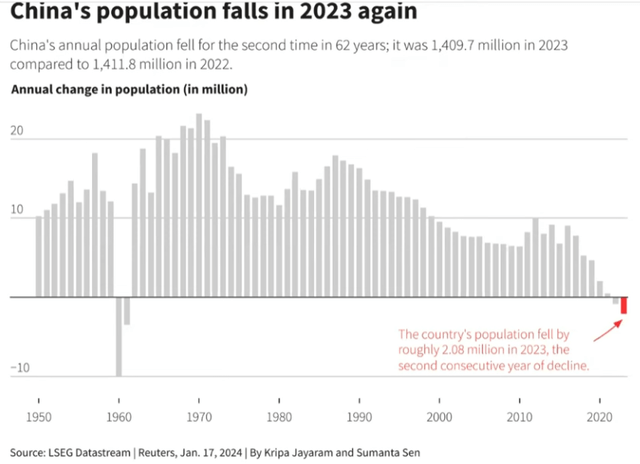

China’s population has peaked. It has now declined for two consecutive years, and this population reduction should only accelerate in the coming years and decades.

In 2020, China’s average age of 38.4 years old surpassed that of the US for the first time in recorded history. Remarkably, in 1978, China’s average age stood at 21.5 years. In the nearly 5 decades between then and now, China has enjoyed a very strong demographic tailwind of high growth in the working-age population combined with falling old-age and child dependency ratios.

This demographic boost has quickly reversed to result in a headwind to economic growth as the working-age population steadily declines while the old-age dependency ratio climbs.

Reuters

After peaking at a little over 1.4 billion people, China’s population is now virtually destined to decline by millions of people every year for decades.

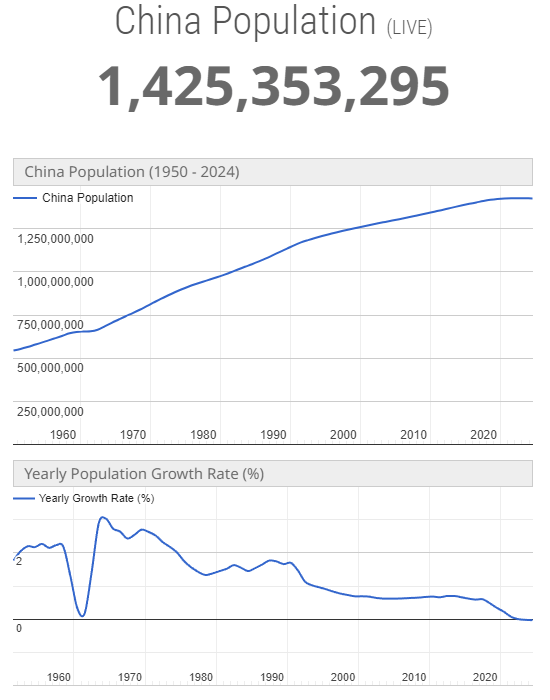

Worldometer

China’s population is almost certain to fall below 1 billion by the end of this century, with the United Nations’ base case China population in 2100 at 767 million and a mere 488 million for its low birth rate scenario.

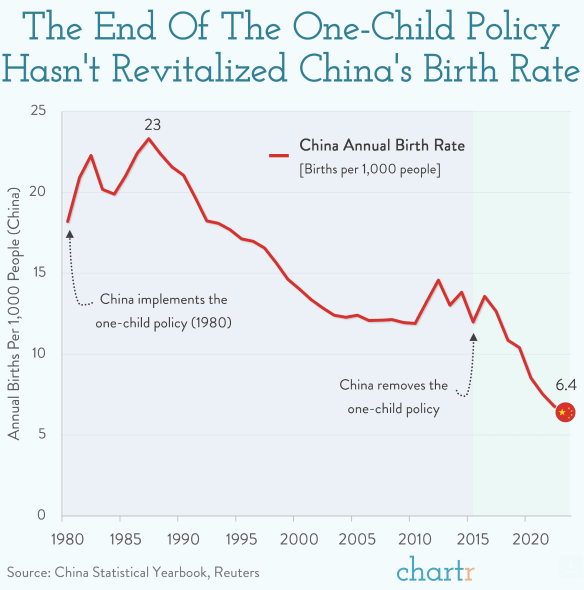

While it is almost unfathomable to think that China’s population could decline by almost 1 billion people by 2100, one should not discount that possibility. After all, China’s birth rate has plummeted over the last decade after already declining significantly in the preceding decades.

Chartr

Part of the reason for this decline is cultural. As opportunities for women have expanded, desire for childbearing has waned. And the marriage rate has collapsed to a record low as the popularity of dating apps has surged. Also, across most of the world, declining religiosity is associated with falling birth rates, which means that China’s declining religiosity may also play a role.

Another reason for the declining birth rate is itself demographic. The longstanding one-child policy led to a dramatic surge in male births over female births, now leading to a far larger population of men than women in their childbearing years.

Despite everything the Chinese government has done to try to increase the birth rate, younger Chinese people have become increasingly uninterested.

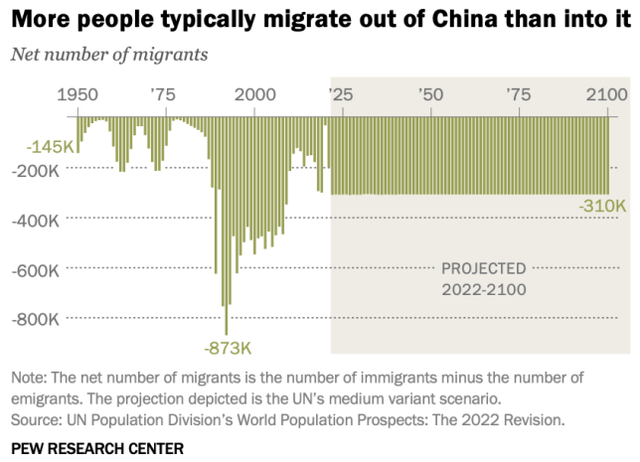

On top of a falling birth rate, China also suffers from negative net migration. Far more people are emigrating out of China than are immigrating into it. That is projected to continue for the foreseeable future.

Pew Research

With deaths greatly outnumbering births and net migration deeply in the negative, China’s population will continue to shrink at an accelerating rate over the coming decades.

This falling population, certainly when combined with the country’s other issues, seems likely to put downward pressure on China’s aggregate demand. And with the exports lever of growth weakening, economic output should likewise decline.

Permanently declining aggregate demand and economic output do not bode well for the long-term prospects of Chinese stocks.

3. China Presents Unique Political Risks For Foreign Stockholders

The Chinese government, which is officially communist and strongly centralized under the authority of President Xi Jinping, presents a unique risk to foreign shareholders of Chinese stocks.

Consider, for example, that many of China’s largest public companies are state-owned enterprises in which the Chinese government owns a controlling stake in the company.

Another point is that non-Chinese investors cannot even directly own Chinese stocks. Instead, they own tracking vehicles designed to mimic the performance of their China-listed equivalents. This may not seem like a big deal, but it presents non-Chinese investors with even less recourse in the case that the Chinese government unilaterally decides to delist stocks.

On top of that issue, consider also the magnitude of political risks for Western investors who are invested in Chinese stocks. If the US further ramps up its trade war against China, or if a multi-national war breaks out over Taiwan, it would not be surprising to see China simply confiscate foreign invested capital.

After all, this would not be the first time that China had sharply and definitively retreated from foreign trade. Five centuries ago, at a time when China boasted the largest naval fleet in the world, the Ming Dynasty burned their ships and turned inward toward isolationism.

Of course, risks could also come from the US government, which could decide to take measures to restrict US investors from owning Chinese stocks. Certain Chinese stocks have already been delisted in the US in the past. It could happen in the future as well.

But the potential negative impacts are not limited to “all or nothing” risks. Lack of standard rule of law measures could hurt investors in other ways.

The slowly collapsing Chinese property market, including the unwinding of developer Evergrande, seems to have triggered a massive outflow of foreign capital from China this year. So far, Chinese authorities have been reluctant to force insolvent developers like Evergrande into bankruptcy, which exposes bondholders to similar levels of risk as stockholders.

Chinese regulators could also make it harder to sell Chinese stocks. For example, the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission recently placed limits on the amount of shares institutional investors and brokerages can sell. These kinds of restrictive measures could be ramped up and strengthened especially for foreign investors in an attempt to prevent further leakage of foreign capital.

Bottom Line

Sometimes stocks are cheap for a reason.

Rather than Chinese stocks suffering from “temporary weakness,” we think the spike in Chinese stock prices during the COVID-19 pandemic represented “temporary strength” due to a one-time surge in exports, largely to the US. In the long run, we remain bearish on both the Chinese economy and Chinese stocks. We simply see no catalyst for a sustained rebound going forward.

We do, however, see plenty of catalysts for certain high-yielding stocks in the US with similarly cheap (or cheaper!) valuations as what one could get in China.

To name a handful of examples, consider the following:

- Cleveland, Ohio-based regional bank TFS Financial (TFSL) offers a dividend yield of about 8.5% with a reasonable ~70% payout ratio. The bank’s loan delinquency rate remains low at about 0.17% even while the average yield on loans continues to creep higher. The bank also trades at a massive, ~62% discount to book value.

- W. P. Carey (WPC) is a multi-national net lease REIT focused primarily on industrial manufacturing and logistics properties in the US and Europe as well as essential retail in Europe. The REIT took a hit recently from the swift disposition of its single-tenant office properties as well as from a few unexpected tenant issues reported in Q4. But these issues are more than priced into the stock at an AFFO (adjusted funds from operations) multiple of 12.1x is well below its 5-year average of 15x, and its rebased, 6%-yielding dividend is well-covered at a payout ratio in the low 70% area.

- Lastly, global renewable power producer Brookfield Renewable (BEP, BEPC) is currently discounted due to its heavy use of debt and large development pipeline of projects under construction that are not yet generating revenue. But interest rates are expected to decline over the next year or so, which should cause this headwind to turn into a tailwind. BEP should also majorly benefit from the growth of AI as new data centers utilize newly built renewable power sources to reduce the burden on electric grids. At an FFO payout ratio a little above 80%, BEP’s 6%-yielding dividend looks safe.

Given the far greater economic prospects and rule of law in North America, we would much rather own names like this than go bottom fishing in the Chinese stock market.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.