February 7, 2023

Policymakers in Washington, London, and other allied capitals during 2022 pushed the outer limits of economic statecraft to tackle challenges ranging from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine to China’s growing military and technological capabilities. Notably, President Joe Biden continued his predecessor’s approach of weaponizing different tools and executive offices in the economic coercion space—further blurring once clear distinctions between sanctions, export controls, import restrictions, tariffs, and foreign investment reviews. Breaking down longtime silos between those different policy instruments proved effective at exerting economic pressure on Moscow, Beijing, and other targets over the past year, and these tools will be a durable feature of U.S. and allied policy going forward.

In addition to the breadth of economic tools employed by the United States, one of the year’s most consequential developments was the Biden administration’s emphasis on employing trade restrictions in close coordination with traditional allies and partners. In a sharp break from the prior administration, President Biden, on the campaign trail and through last year’s comprehensive review of U.S. sanctions, articulated a strong preference for multilateral solutions to global challenges. That policy approach was put vividly into practice in 2022 following the Kremlin’s further invasion of Ukraine as a coalition of more than 30 democracies—together accounting for more than half of global economic output—clamped severe restrictions on trade with Russia. Such close coordination magnified the impact of sanctions by making them more challenging to evade, and raised questions regarding whether coalition policymakers can muster a similarly united front in response to other pressing challenges like an increasingly powerful China. Despite their close alignment, small divergences between the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom—with respect to both targets and, more importantly, matters of interpretation such as whether entities controlled by a sanctioned party are restricted—presented daunting compliance challenges for multinational businesses.

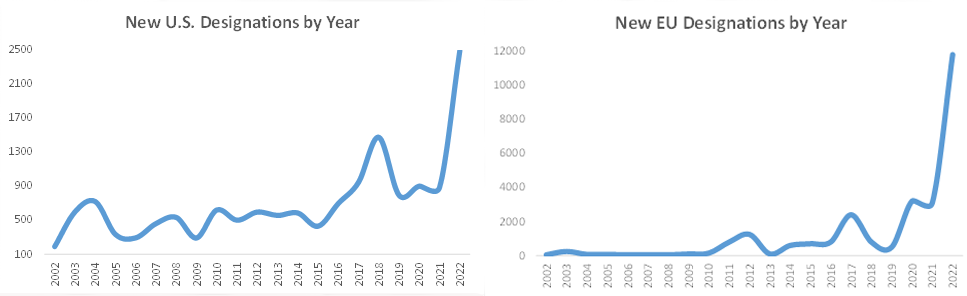

Over the past year, policymakers broke new ground by, for the first time ever, imposing sweeping trade controls on a major, globally connected economy—including adding a record-shattering number of (mostly Russian) individuals and entities to sanctions lists:

The past year was also remarkable for its many instances of genuine policy innovation, as officials immobilized Russia’s foreign reserves, introduced a novel price cap on seaborne Russian crude oil and petroleum products, imposed unprecedented controls on China’s access to advanced semiconductors, and laid the groundwork for possible new regimes in the United States and Europe to review outbound foreign investments. However, U.S. and allied governments were not the only active players. From Moscow to Beijing, targets of economic coercion have not sat still, imposing their own countermeasures, promulgating regulations to impede domestic compliance with “unfriendly country” actions, and hindering the ability of outside parties to even learn about the ownership or control of certain parties that may be impacted by restrictions. In addition to governmental action, 2022 was notable for the extreme de-risking seen especially in Russia, with more than a thousand companies deciding to pull back from operations in that country before any regulation demanded it of them. This “self-sanctioning” was not part of the coalition’s strategy, and its implications for a diminished ability of allied policymakers to effectively calibrate measures going forward—when businesses will undoubtedly remain skittish—makes the entire canon of economic statecraft uncertain. Multinational enterprises must also contend with the U.S. Department of Justice’s emerging view of sanctions as the “new” Foreign Corrupt Practices Act—portending an uptick in civil and criminal enforcement activity. By any measure, 2022 was a historically busy period for the imposition of new trade controls, and the pace of policy change shows few signs of slowing during the year ahead.

Contents

I. Global Trade Controls on Russia

A. Comprehensive Sanctions on Covered Regions of Ukraine

B. Sectoral Sanctions

C. Blocking Sanctions

D. Export Controls

E. Import Prohibitions

F. New Investment Prohibitions

G. Services Prohibitions

H. Price Cap on Crude Oil and Petroleum Products

I. Possible Further Trade Controls on Russia

II. U.S. Trade Controls on China

A. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

B. Technological Competitiveness Legislation

C. Export Controls

D. Defense Department List of Chinese Military Companies

E. Investment Screening

III. U.S. Sanctions

A. Iran

B. Syria

C. Venezuela

D. Nicaragua

E. Afghanistan

F. Myanmar

G. Crypto/Virtual Currencies

H. Other Sanctions Developments

IV. U.S. Export Controls

A. Commerce Department

B. State Department

V. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)

A. CFIUS Annual Report

B. National Security Factors

C. Enforcement and Penalty Guidelines

D. Outbound Investment Screening

VI. European Union

A. Trade Controls on China

B. Sanctions Developments

C. Export Controls Developments

D. Foreign Direct Investment Developments

VII. United Kingdom

A. Trade Controls on China

B. Sanctions Developments

C. Export Controls Developments

D. Foreign Direct Investment Developments

I. Global Trade Controls on Russia

Following the Kremlin’s further invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, leading industrial economies—including the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Japan—swiftly imposed aggressive and coordinated trade controls on Russia. Spurred by global outrage and fierce Ukrainian resistance, 2022 saw the imposition of a cascade of restrictions that would have been unthinkable in even the recent past, including comprehensive sanctions on Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine, wide-ranging sectoral sanctions, blocking sanctions, export controls, import bans, new investment bans, services bans, and an innovative price cap on seaborne Russian crude oil and petroleum products. Taken together, these measures—which target key pillars of Russia’s economy (and its principal sources of hard currency) such as the country’s financial sector, energy sector, and military-industrial complex—were calculated to deny the Kremlin the resources needed to prosecute the war in Ukraine and degrade Russia’s ability to project power abroad.

As the war in Ukraine nears its first anniversary, allied trade restrictions appear to be exacting a toll on Russia’s economy, which, despite soaring energy prices, contracted during 2022. Notably, more than a thousand companies have ceased or curtailed their operations in Russia since the start of the war—an exodus that by and large was not mandated by regulation but that nonetheless threatens to further dim Russia’s long-term growth prospects. Meanwhile, the coalition continues to hold additional policy options in reserve. Depending upon how events unfold, the allies could potentially further restrict dealings involving Russia by imposing blocking sanctions on additional Russian elites, designating the Government of the Russian Federation, moving to seize Russian assets to fund Ukraine’s reconstruction, or expanding existing sanctions and export controls to include a complete embargo on trade in goods and services.

A. Comprehensive Sanctions on Covered Regions of Ukraine

On February 21 and 22, 2022, the United States and key allies imposed comprehensive sanctions on the Russia-backed separatist regions of Ukraine known as the Donetsk People’s Republic (“DNR”) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (“LNR”). This initial round of sanctions came as President Putin recognized the two breakaway regions as independent states and quickly ordered Russian troops to enter the regions for an ostensible “peacekeeping” mission. Just hours after the dramatic Russian announcement, President Biden signed Executive Order (“E.O.”) 14065, which imposes broad, jurisdiction-wide sanctions on the DNR and LNR, plus any other regions of Ukraine as may be determined by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury (collectively, the “Covered Regions”). As we wrote in an earlier client alert, that measure by President Biden is nearly identical to Executive Order 13685, which announced President Barack Obama’s imposition of comprehensive sanctions on the Crimea region of Ukraine in 2014.

In particular, E.O. 14065 prohibits: (1) new investment in the Covered Regions by a U.S. person; (2) the importation into the United States of any goods, services, or technology from these regions; as well as (3) the exportation from the United States, or by a U.S. person, of any goods, services, or technology to these regions. The Order further authorizes blocking sanctions on any person determined by the Secretary of the Treasury to be a person operating in the Covered Regions. The European Union and the United Kingdom have adopted similarly broad restrictions, yet these are not total bans on dealings with the regions. EU restrictions target Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia, while UK restrictions only target Donetsk and Luhansk.

As a practical matter, sanctions on these particular regions of Ukraine present substantial compliance challenges, very similar to those seen in Crimea, as U.S., EU, and UK persons are again prohibited from engaging in transactions involving regions that are not internationally recognized states. Moreover, the precise boundaries of the sanctioned regions are unsettled. The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) has indicated in published guidance that the DNR and the LNR do not presently encompass the entire Ukrainian oblasts, or provinces, of Donetsk and Luhansk. Similarly, EU restrictions cover areas of the relevant oblasts which are not under the control of the Ukrainian authorities. The United Kingdom, on the other hand, relies on the territorial definition outlined in Decree Number 32/2019 issued by the President of Ukraine. It is also conceivable that the “Covered Regions” could in future be extended to include some or all of the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions of Ukraine that Russia purported to annex in September 2022, in line with the European Union’s approach. For purposes of determining whether a particular location in eastern Ukraine is within the Covered Regions—and is therefore subject to comprehensive U.S. sanctions—OFAC has not yet publicly delineated the borders of those regions, but has offered that “U.S. persons may reasonably rely on vetted information from reliable third parties, such as postal codes and maps.”

Importantly, as of this writing, the Russian Federation is not subject to comprehensive sanctions. That is, U.S. persons are prohibited from engaging in substantially all transactions involving only a small number of jurisdictions, namely Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and the Crimea, Donetsk People’s Republic, and Luhansk People’s Republic regions of Ukraine. The remaining U.S. sanctions programs, and all EU and UK sanctions programs, including sanctions targeting Russia, are generally list-based—meaning that U.S. persons are restricted from engaging in certain transactions involving certain specified parties, as well as those parties’ direct and indirect majority-owned entities (or, in the case of the European Union and United Kingdom, those parties’ direct and indirect majority-owned and/or controlled entities). That said, as discussed below, the number of Russia-related parties that are subject to list-based sanctions exploded during 2022 and is poised for further growth during the year ahead.

In addition to the comprehensive sanctions on the DNR and LNR discussed above, an unusual feature of the sanctions programs targeting Russia are the sectoral sanctions, under which it is prohibited to engage in certain narrow types of activities with certain designated entities, as set forth on the Sectoral Sanctions Identifications (“SSI”) List or the Non-SDN Menu-Based Sanctions (“NS-MBS”) List administered by OFAC and the equivalent lists maintained by other key allies, including the European Union and the United Kingdom. This type of sectoral designation limits the types of interactions a targeted entity is allowed to undertake with U.S., EU, and UK persons pursuant to a series of OFAC “Directives” and EU and UK regulations that for nearly a decade have targeted Russia’s financial, energy, defense, and oil industries. Underscoring the narrow scope of the sectoral sanctions on Russia, OFAC expressly provides that, absent some other prohibition, all other lawful U.S. nexus dealings involving a targeted entity are permitted. That same approach in relation to sectoral sanctions has been adopted in the European Union and the United Kingdom.

Immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Biden administration announced four new sectoral sanctions Directives that bar U.S. persons from engaging in certain dealings involving some of the Russian Federation’s most economically consequential institutions. Those restrictions were paralleled by the European Union and the United Kingdom. In particular, the measures restrict Russia’s access to capital by:

- Prohibiting U.S. financial institutions from participating in the primary or secondary market for “new” bonds issued by Russia’s central bank, finance ministry, and principal sovereign wealth fund (collectively, the “Russian Sovereign Entities”);

- Prohibiting U.S. financial institutions from opening or maintaining a correspondent or payable-through account for or on behalf of, or processing a transaction involving, Sberbank or any of its majority-owned entities, thereby cutting off Russia’s largest bank from the U.S. financial system;

- Prohibiting U.S. persons from dealing in “new” debt or “new” equity of 13 major Russian state-owned enterprises and financial institutions, further limiting Russia’s ability to raise new capital for its military activities in Ukraine; and

- Prohibiting U.S. persons, except as authorized by OFAC, from engaging in any transaction involving the three named Russian Sovereign Entities, including any transfer of assets to such entities or any foreign exchange transaction for or on behalf of such entities. This novel sectoral sanctions measure, together with similar restrictions by each member of the Group of Seven (“G7”), has proven especially impactful. While neither the Russian Central Bank, the Russian National Wealth Fund, nor the Russian Ministry of Finance are blocked, using this unique tool the allies effectively immobilized around $300 billion in international reserves that the Russian government had stockpiled to insulate its economy from the effects of sanctions.

During the war’s opening days, the European Union, in another highly impactful move, directed the Belgium-based Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (“SWIFT”) to deny select Russian banks access to its financial messaging services, which serve as the principal means for global financial institutions to send and receive transaction-related information.

The coalition’s early use of sectoral sanctions, which we discuss in depth in a previous client alert, was animated by a policy interest in imposing tangible costs on the Kremlin for invading Ukraine, while minimizing the collateral consequences of targeting one of the world’s largest and (then) most interconnected economies. As the war in Ukraine has stretched on, the allies have demonstrated an increasing willingness to impose a variety of severe restrictions on Russia, including the expansive use of blocking sanctions.

Since February 2022, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, in a historic burst of activity, have each added approximately 1,500 new Russia-related individuals and entities to their respective consolidated lists of sanctioned persons. While the lists do not always overlap, increasing the compliance burden on multinational companies, the level of coordination among the allies has been particularly impactful. As an example of the sweeping nature of the new designations, in the United States, of all the parties that have been named to OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN”) List over the decades, around one in ten were designated in just the past year for their activities involving Russia.

Blocking sanctions are arguably the most potent tool in a country’s sanctions arsenal, especially for countries such as the United States with an outsized role in the global financial system. Upon becoming designated an SDN (or other type of blocked person), the targeted individual or entity’s property and interests in property that come within U.S. jurisdiction are blocked (i.e., frozen) and U.S. persons are, except as authorized by OFAC, generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the blocked person. The same applies to persons designated by the European Union or the United Kingdom. The SDN List, and its EU and UK equivalents, therefore function as the principal sanctions-related restricted party lists. The effects of blocking sanctions often reach beyond the parties identified by name on these lists. By operation of OFAC’s Fifty Percent Rule (and in the EU and the UK, the ownership and control test), restrictions generally also extend to entities owned 50 percent or more in the aggregate by one or more blocked persons (or, in the case of the EU and UK, to entities owned more than 50 percent or controlled by a blocked person, with the EU indicating that aggregation is possible), whether or not the entity itself has been explicitly identified.

During 2022, the allies repeatedly used their targeting authorities to block Russian political and business elites, as well as substantial enterprises in sectors such as banking, energy, defense, aerospace, and mining seen as critical to financing and sustaining the Kremlin’s war effort. Notable designations included:

- Government officials, including President Vladimir Putin, as well as Russia’s foreign minister, defense minister, central bank chief, and 328 members of the Russian State Duma. Belarus’s President Alyaksandr Lukashenka was also re-designated after permitting Russian troops to launch attacks on Ukraine from Belarusian soil;

- Prominent Russian oligarchs such as Alisher Usmanov and Vladimir Potanin and, in the European Union and the United Kingdom, Roman Abramovich;

- Major financial institutions, including VTB Bank and Sberbank, that together represent around 80 percent of Russia’s banking sector by assets;

- Energy firms, including Nord Stream 2 AG, the Swiss company in charge of developing a new gas pipeline between Germany and Russia; while Germany has suspended the approval process for Nord Stream 2 (disallowing its operation), notably the European Union and the United Kingdom have not followed the United States in designating Nord Stream 2 AG;

- Defense and aerospace firms, including the state-owned defense conglomerate Rostec and the mercenary group Private Military Company Wagner, which have been instrumental in equipping and manning Russia’s military operation in Ukraine; and

- Extractive firms such as Alrosa, the world’s largest diamond mining company and a major source of revenue for the Russian state.

Many of those U.S. designations were made under the authority of Executive Order 14024, which we discussed in depth in a previous client alert. Importantly, E.O. 14024 authorizes blocking sanctions against persons determined to operate in certain sectors of the Russian economy determined by the Secretary of the Treasury. Underscoring the uncertain business environment in Russia, parties in multiple sectors now operate under the threat of being added to the SDN List, including those operating in the technology, defense and related materiel, financial services, aerospace, electronics, marine, accounting, trust and corporate formation services, management consulting, or quantum computing sectors of Russia’s economy. Moreover, OFAC has indicated that it is prepared to use its authorities to impose blocking sanctions on any non-U.S. persons otherwise involved in circumventing U.S. sanctions, solidifying Russia’s grasp on occupied regions of eastern Ukraine, or arming, equipping, or materially supporting the Russian military.

In addition to economic and financial sanctions, the United States and its allies rapidly expanded their export control regimes targeting Russia and Belarus in response to Moscow’s further invasion of Ukraine and Belarus’s support of the effort.

Significantly, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) imposed a license requirement on all controlled dual-use items subject to its jurisdiction when destined for, reexported to, or transferred within Russia or Belarus. In tandem with this action, BIS expanded the scope of U.S. licensing requirements on foreign-produced items exported, reexported, or transferred within Russia or Belarus in a range of circumstances, such that:

- Foreign-made items that incorporate more than 25 percent controlled U.S.-origin content are subject to BIS’s export licensing regime under the traditional application of the de minimis rule;

- Foreign-made items that are the “direct product” of controlled U.S.-origin technology or software, or of a manufacturing facility or equipment derived from such controlled U.S. technology or software, and are items of a kind described on the S. Commerce Control List (i.e., not EAR99 items), or are items that could be used in identified industrial sectors, are subject to an export license requirement when destined for any person in Russia or Belarus;

- Foreign-made items that would be designated EAR99 (i.e., generally not controlled) and are a “direct product” of controlled U.S.-origin technology or software, or a manufacturing facility or equipment derived from such controlled technology or software, are subject to an export license requirement when destined for any Russian or Belarusian military end user identified on the Entity List; and

- With respect to both of those new foreign direct product rules, items produced in a partner country that has implemented substantially similar export controls on Russia and Belarus are exempt from the U.S. license requirement in order to avoid duplicate licensing efforts.

Further, BIS expanded the scope of pre-existing prohibitions related to military end users and military end uses in Russia and Belarus to cover any item subject to the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”), including items “subject to the EAR” by operation of one of the foreign direct product rules described above. The controls described above produced immediate impacts as Russia’s military, absent new shipments of advanced technology, reportedly was forced to retrieve low-end semiconductors from household appliances such as dishwashers and refrigerators. For a more detailed discussion of those controls, please see our February 2022 client alert.

BIS also expanded the scope of its licensing control to include EAR99 items—that is, items that are not described by an Export Control Classification Number (“ECCN”) on the EAR’s Commerce Control List—for Russia and Belarus. These controls largely parallel EU controls on certain targeted goods, equipment, parts, and materials for use in significant industry sectors, including oil refining (in addition to pre-existing controls on items used in oil and gas exploration and production), industrial and manufacturing activities, production of chemical and biological agents, quantum computing, and advanced manufacturing. In addition, BIS published rules to implement a ban on “luxury goods” destined for Russia or Belarus or to sanctioned Russian or Belarusian oligarchs, regardless of their location.

The European Union and the United Kingdom have followed a similar approach, though the lists of goods targeted differ between jurisdictions. In general terms, the EU and UK lists are organized under broad headings such as “goods which may enhance Russia’s military and technological advancement,” “goods that may enhance Russia’s industrial capabilities,” or “critical industry goods.” The expansive headings allow the European Union and the United Kingdom to include numerous groups of seemingly unrelated items within their restrictions, adding to the complexity of these measures.

The United States has also prohibited the exportation, reexportation, sale, or supply from the United States, or by a U.S. person, of U.S. Dollar-denominated banknotes to the Government of the Russian Federation or any person located in the Russian Federation. The European Union and the United Kingdom have imposed equivalent restrictions on the export of Euro and Sterling banknotes, respectively.

As a general matter, export license applications under the new export controls on Russia and Belarus will, except in limited circumstances, be reviewed subject to a policy of denial, essentially imposing an embargo on all U.S.-origin dual-use items, items produced with dual-use software and technology, and a broad range of non-dual-use items used in multiple industrial sectors, for Russia and its cooperating neighbor. EU and UK authorities have taken a similar approach.

Of particular note is BIS’s aggressive use of export controls to target the Russian and Belarusian commercial aviation sectors. In light of the wide-ranging use of U.S.-origin parts, equipment, and technology in commercial aviation applications, expanded U.S. export controls have cut off many private and commercial aircraft owned, leased, or operated by Russian or Belarusian persons from transiting to or from those countries or receiving parts or services provided by U.S. persons. In addition, BIS has responded to the Russian government’s effective nationalization of hundreds of U.S. and European aircraft by issuing temporary denial orders against major Russian airlines and by publishing lists of aircraft that have been flown in violation of U.S. export controls, rendering transactions involving either subject to expansive prohibitions. The EU and UK restrictions on aviation and space goods and technology have added to the logistical complexities facing the aviation sector, and have been further exacerbated by prohibitions on Russian owned, registered, controlled, or chartered aircraft entering or leaving EU and UK airspace.

To encourage compliance and identify potential evasion of the new rules described above, BIS and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) in June 2022 issued a first-of-its-kind joint alert to financial institutions urging them to apply heightened due diligence to transactions with a higher risk of facilitating export control evasion. The joint alert includes a list of commodities that BIS has identified as presenting special concern because of their potential diversion to military applications in Russia and Belarus, including aircraft parts, cameras, global positioning systems, integrated circuits, oil field equipment, and related items, as well as a list of transshipment hubs that present diversion risks to Russia and Belarus. It also highlights transactional “red flags” that are useful both to financial institutions and other industry participants.

In addition to restricting exports to Russia, starting in March and April 2022 the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom banned the importation of certain Russian-origin goods—principally those consisting of items closely associated with Russia or that have the potential to generate hard currency for the Kremlin.

The Biden administration first used this particular policy tool by barring imports into the United States of certain energy products of Russian Federation origin, namely crude oil, petroleum, petroleum fuels, oils, and products of their distillation, liquified natural gas, coal, and coal products. Intending to limit Russian revenue without driving up global energy prices, OFAC published guidance noting that Russian-origin energy products other than those specified in Executive Order 14066 remain potentially eligible for importation into the United States. OFAC further indicated that, absent some other prohibition, such as the involvement of a blocked person, non-U.S. persons would not risk U.S. sanctions liability for continuing to import Russian-origin energy products into third countries that have not imposed such an import ban. As Russia’s war in Ukraine continued, the Biden administration subsequently barred the importation into the United States of Russian Federation origin fish, seafood, alcoholic beverages, non-industrial diamonds, and eventually gold. As with other Russia-related sanctions authorities, the Secretary of the Treasury has broad discretion under Executive Order 14068 to, at some later date, extend the U.S. import ban to additional Russian-origin products.

While U.S. imports from Russia historically have been minimal, the same is not true for the European Union and the United Kingdom. Consequently, for the restrictions to be meaningful, the EU and UK import measures have had to be similarly broad—and they are. The European Union has banned coal, crude oil and petroleum products, iron and steel products, gold and the broad category of “revenue-generating goods,” which is a catch-all for any other items the European Union may want to restrict. The United Kingdom has prohibited the import of arms and related materiel, iron and steel products, oil and oil products, coal and coal products, liquified natural gas, gold, gold jewelry, and processed gold. However, there remain significant differences between the transatlantic partners in this regard, reflecting their different ranges of independence from the Russian economy and its energy sector. Notably, the European Union and the United Kingdom have not yet restricted the import of Russian liquified natural gas. EU Member States such as Hungary, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Czechia also negotiated exceptions to the prohibitions described above, the most notable of which has the effect of excluding crude oil delivered by pipeline from the import ban.

Furthermore, highlighting the degree of bipartisan support for limiting Russia’s access to the U.S. market, the U.S. Congress in April 2022 enacted legislation codifying into law the Biden administration’s Russian oil import ban, as well as suspending the United States’ permanent normal trade relations with Russia and Belarus, thereby exposing products originating from those two countries to increased U.S. tariffs. Similarly, the European Union and the United Kingdom have revoked Russia’s most favored nation trading status, triggering higher tariffs.

F. New Investment Prohibitions

In parallel with efforts to restrict Russian imports into the United States, and drawing on many of the same legal authorities, the Biden administration during March and April 2022 also imposed a series of progressively broader prohibitions on new investment in the Russian Federation.

Specifically, President Biden in quick succession signed three separate Executive Orders prohibiting U.S. persons, wherever located, from making a “new investment” in the energy sector in the Russian Federation (E.O. 14066), then in any other sector of the Russian Federation economy as may be determined by the Secretary of the Treasury (E.O. 14068), and eventually on April 6, 2022 in all sectors of the Russian Federation economy (E.O. 14071). By encompassing the entire Russian economy, the last of those three Executive Orders in effect swallows the other two. In a sign of the blistering pace at which new trade restrictions on Russia were being rolled out during the war’s earliest phases, the business community had to wait two months after the Biden administration’s banning of all “new investment” for guidance as to what “new investment” entails. OFAC was operating at a high cadence in rolling out new actions and did not have the bandwidth to immediately provide the guidance, frequently asked questions (“FAQs”), and other documentation that typically accompany such meaningful new measures.

In a set of FAQs released on June 6, 2022, OFAC for the first time detailed how the agency understands what does (and does not) constitute a prohibited new investment in Russia. Broadly speaking, OFAC considers “new investment“ to mean a U.S. person making a commitment of capital or other assets, on or after the effective date of the relevant Executive Order (in most cases, April 6, 2022), for the purpose of generating returns or appreciation within the Russian Federation. OFAC interprets Executive Order 14071 as prohibiting U.S. persons from, among other things, purchasing both new and existing debt and equity securities issued by any entity located in the Russian Federation—regardless whether the issuer is subject to blocking or sectoral sanctions and regardless when the debt or equity was issued. OFAC has further indicated that E.O. 14071 prohibits U.S. persons from purchasing debt and equity securities issued by any entity located outside of Russia that has certain close ties to Russia such as deriving 50 percent or more of its revenues from investments inside the Russian Federation.

Crucially, however, OFAC has advised that the agency generally does not view the new investment prohibition as applying to ordinary course commercial transactions involving Russia, including exports or imports of goods, services, or technology, or related sales or purchases. Notably for multinational enterprises, U.S. persons may continue to fund, but not expand, their existing subsidiaries and affiliates located in Russia. U.S. persons may continue to hold previously acquired securities of non-sanctioned Russian issuers and may also divest such securities, subject to certain conditions. Such divestment transactions are potentially permissible, provided that the transaction does not involve a blocked person, the ultimate buyer is a non-U.S. person, and the transaction is not otherwise prohibited by OFAC. Notwithstanding those and other exceptions, the U.S. prohibition on new investment in the Russian Federation further complicates an already challenging local business environment and, by barring new or expanded operations, is likely to encourage multinational companies’ continued flight from Russia. This self-sanctioning by private actors was not a part of the well-laid sanctions plan that the coalition developed in the run-up to the February 2022 attack. Indeed, in recent weeks, the United States especially has redoubled efforts to emphasize that it desires certain businesses to remain in Russia despite the breadth of sanctions and related restrictions.

The United Kingdom’s approach to investment restrictions has been equally broad, while the European Union has taken a more limited approach of strictly banning investment in the energy sector in Russia, as well as the Russian mining and quarrying sector, while carving out exceptions for certain raw materials.

As the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine stretched on, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom in May and September 2022 reached deeper into their respective policy toolkits to ban the exportation to Russia of certain professional and technological services.

Executive Order 14071—the broad and flexible legal authority that underpins many of the U.S. Government’s later trade restrictions on Russia—prohibits the exportation from the United States, or by a U.S. person, of any category of services as may be determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, to any person located in the Russian Federation. Acting pursuant to that authority, the United States during 2022 barred U.S. exports to Russia of accounting, trust and corporate formation, and management consulting services, as well as quantum computing services. The rationale for targeting those particular services—the provision of which is also potentially grounds for designation to the SDN List—appears to be a U.S. policy interest in denying Moscow access to services with the potential to enable sanctions evasion or bolster the Russian military.

Although the U.S. services bans contain exceptions, such as permitting the provision of services to entities located in Russia that are owned or controlled by U.S. persons, OFAC otherwise interprets those measures in a very broad manner. For example, the agency has noted that, for the purposes of E.O. 14071, the term “accounting services“ includes “services related to the measurement, processing, and evaluation of financial data about economic entities.” The term “management consulting services“ includes, among other activities, “services related to strategic business advice.” In light of the prohibitions’ seemingly unbounded reach, many leading professional services firms—whose offerings are key to operating a multinational business—have opted to withdraw from the Russian market rather than risk triggering U.S. sanctions.

The European Union and the United Kingdom have imposed equally wide-ranging services prohibitions. The European Union has restricted the provision of accounting, auditing, bookkeeping and tax consulting, business and management consulting, public relations, information technology consulting, architectural and engineering, legal advisory, market research, public opinion polling, advertising, and technical testing and analysis services. Both jurisdictions also restricted trust and corporate formation services—which have historically been key tools for wealthy Russians to shield their assets.

Despite core similarities across the three jurisdictions, important different exceptions apply. Most notably, the European Union allows for these services to be provided to Russian entities that are owned by, or solely or jointly controlled by, an entity incorporated under the laws of an EU or European Economic Area Member State, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, South Korea, or Japan. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom allows for certain exceptions in relation to compliance with UK statutory or regulatory obligations.

Within the financial services sector, the United Kingdom prohibited its financial institutions from establishing correspondent banking relationships with designated persons, and proceeded to designate all major Russian banks. To further tighten access to its financial infrastructure, the European Union implemented restrictions relating to deposits being held by EU credit institutions, such that Russian natural or legal persons and entities directly or indirectly owned more than 50 percent by them cannot make deposits greater than 100,000 Euros. A prohibition on the provision of crypto-asset wallet, account, or custody services, regardless of the value of the assets, also applies in the European Union. The United Kingdom has not implemented equivalent measures, but it has subjected crypto-asset exchange providers and custodian wallet providers to strict reporting obligations.

In late 2022 and early 2023, the allies also introduced new and ambitious forms of services bans, discussed more fully below, designed to cap the price of seaborne Russian crude oil and petroleum products.

H. Price Cap on Crude Oil and Petroleum Products

To minimize the Kremlin’s ability to profit from surging energy prices stemming from its invasion of Ukraine, the G7 countries in September 2022 committed to impose a novel measure to squeeze Russia’s chief source of revenue—a price cap on Russian-origin crude oil and petroleum products.

Effective December 5, 2022, the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom, alongside the European Union and Australia (collectively, the “Price Cap Coalition”), prohibited the provision of certain services that support the maritime transport of Russian-origin crude oil from Russia to third countries, or from a third country to other third countries, unless the oil has been purchased at or below a specified price. A separate price cap with respect to Russian-origin petroleum products became effective on February 5, 2023. The types of services that are potentially restricted varies modestly among the Price Cap Coalition countries, but generally includes activities such as brokering, financing, and insurance. A detailed analysis of the price cap, and how it is being implemented by key members of the Price Cap Coalition, can be found in our previous client alert.

From a policy perspective, the price cap is intended to curtail Russia’s ability to generate revenue from the sale of its energy resources, while still maintaining a stable supply of these products on the global market. The measure is also designed to avoid imposing a blanket ban on the provision of all services relating to the transport of Russian oil and petroleum products, which could have far-reaching and unintended consequences for global energy prices. Accordingly, the price cap functions as an exception to an otherwise broad services ban. Best-in-class maritime service providers, which are overwhelmingly based in Price Cap Coalition countries, are permitted to continue supporting the maritime transport of Russian-origin oil and petroleum products, but only if such oil or petroleum products are sold at or below a certain price.

In order to steer clear of a potential enforcement action, service providers from Price Cap Coalition countries that deal in seaborne Russian oil or petroleum products will need to be able to provide certain evidence that the price cap was not breached in regard to the shipment that they are servicing. For example, the United States, United Kingdom, and European Union have each set forth a detailed attestation process by which maritime transportation industry actors can benefit from a “safe harbor” from prosecution arising out of violations by third parties. By obtaining price information or an attestation from relevant counterparties, ship owners, charterers, insurers, financial institutions, and others throughout the maritime supply chain may substantially mitigate their risk of non-compliance arising out of misrepresentations or evasive actions taken by third parties in violation of the price cap programs. Relevant authorities in those three jurisdictions have indicated that compliance with the recordkeeping and attestation framework will generally shield a service provider from the otherwise strict liability regime.

It remains to be seen whether other countries will eventually join the Price Cap Coalition or agree to implement similar restrictions in the future, which could create additional complexity in the global energy supply chain where Russian-origin oil or petroleum products are involved. As of this writing, the price cap seems to be having a modest impact on Russian oil revenues. In setting the initial price cap on Russian-origin crude oil at $60 per barrel—above the prevailing market price for Russian Urals—policymakers appear to have offered maritime service providers a gentle introduction to a novel and complex policy instrument. As market participants become more familiar with the mechanics of the price cap, the Price Cap Coalition may periodically ratchet down the relevant price caps to further squeeze Russian energy revenue.

I. Possible Further Trade Controls on Russia

Although leading democracies during 2022 introduced a dizzying array of trade restrictions on Russia, the coalition has not yet exhausted its policy toolkit. The allies could, in coming months, further increase pressure on the Kremlin by imposing blocking sanctions on yet more Russian banks and Russian elites, including especially oligarchs whose vast business interests may offer inviting targets. In the event of a substantial new provocation by Moscow, it is not out of the question that the Biden administration could follow the model developed in Venezuela by imposing blocking sanctions on the entirety of the Government of the Russian Federation.

Officials in Washington and Brussels have also begun to weigh how to fund Ukraine’s eventual reconstruction. Building on initiatives such as the U.S. Department of Justice’s Task Force KleptoCapture and the multilateral Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force, which are pursuing seizure and forfeiture of certain assets belonging to sanctioned parties if they meet legal standards beyond the fact that they are sanctioned, the United States could potentially move to deploy forfeited Russian assets to aid Kyiv. Similarly, the European Commission has been exploring options to pay for the reconstruction of Ukraine with investment proceeds derived from Russian assets currently frozen in the European Union. As we have noted elsewhere, in the United States any effort to redirect private assets—or, more controversially, Russian sovereign assets—would likely require an act of Congress to reduce the not insignificant legal difference and distance between sanctions and seizures, suggesting that any such initiative is unlikely to materialize in the near term.

Finally, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom have so far resisted calls to label Russia a state sponsor of terrorism, or, in the case of the United States, to impose secondary sanctions, citing the risk of fracturing the coalition by penalizing companies based in allied jurisdictions for their dealings involving Russia. The European Parliament has called on EU Member States to work toward the introduction of a legal framework to designate state sponsors of terrorism, so that Russia can be so designated. As noted above, the United States and its allies, while imposing extensive restrictions on Moscow, have also stopped short of comprehensive sanctions and export controls like the U.S. measures that presently apply to Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and certain Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine. Although those sorts of draconian restrictions do not appear to be imminent, the United States and its allies could quickly reconsider such measures in the event of a complete breakdown in relations with Moscow—for example, if the Kremlin were to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine.

II. U.S. Trade Controls on China

Russia’s invasion nearly overshadowed what otherwise would have been the principal trade story of the year: continuing high tensions between Washington and Beijing. During 2022, the Biden administration deployed both traditional and innovative trade restrictions to counter China’s continued troubling activities at home and worrying ambitions abroad. In the U.S. National Security Strategy released in October 2022, the Biden administration squarely addressed the ongoing geopolitical competition between the United States and China, labeling Beijing “the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to advance that objective.” This stark characterization reflects an emerging bipartisan consensus among top U.S. officials and most members of Congress that China represents a “pacing challenge“ to certain U.S. national interests, particularly technological leadership.

In a sea change from longstanding U.S. aversion to state industrial policy, the United States over the past year embraced a protectionist-leaning “modern industrial and innovation strategy“ to counteract China’s influence on the world stage, including through:

- The promulgation of import restrictions on Chinese goods linked to forced labor;

- The passage of multiple legislative packages to incentivize U.S. technological competitiveness;

- The imposition of sweeping export controls on certain advanced integrated circuits, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and supercomputers involving China;

- The furthering of multilateral efforts to limit China’s technological capabilities; and

- The continuation and enhancement of scrutiny of proposed Chinese investments in the United States.

A. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (“UFLPA”) was enacted in December 2021 to deny certain goods produced in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (“Xinjiang”) access to the U.S. market, primarily through the imposition of a rebuttable presumption that all goods mined, produced, or manufactured even partially within Xinjiang are the product of forced labor and are therefore not entitled to entry at U.S. ports. This rebuttable presumption took effect on June 21, 2022. Throughout the second half of 2022, vigorous enforcement of the UFLPA by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”)—which is a unit of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security—led to a substantial volume of goods being denied clearance at various U.S. ports as many suppliers scrambled to trace complete supply chains to ensure compliance.

Guidance released by CBP in June 2022 highlighted cotton, tomatoes, and polysilicon as high-priority sectors for enforcement, but CBP’s targeting has since expanded to include products that incorporate polyvinyl chloride (commonly known as PVC) and aluminum—with the latter a precursor to potentially restricting the import of automobile parts. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has also named over 30 entities to its UFLPA Entity List, as a result of which those entities’ products and services are presumed to be made with forced labor and are prohibited from entry into the United States.

As described in more detail in our 2021 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update, as well as a separate June 2022 client alert, importers of any products that may be suspected to incorporate inputs sourced from Xinjiang, from any entity listed on the UFLPA Entity List, or from companies participating in any one of several of China’s “anti-poverty alleviation” programs should be aware of the new supply chain tracing requirements necessary to demonstrate that the imports are not subject to the rebuttable presumption.

B. Technological Competitiveness Legislation

Alongside efforts to restrict imports that present potential human rights concerns, a key pillar of the Biden administration’s trade policy with respect to China has involved a turn inward by the United States and toward a nationalist industrial policy, including directly subsidizing industries critical to U.S. supply chains and national security. Consistent with the White House’s National Security Strategy—which describes strategic public investment as “the backbone of a strong industrial and innovation base in the 21st century global economy”—the U.S. Congress during 2022 adopted two massive legislative packages that, among other things, direct billions of dollars toward boosting domestic manufacturing.

The CHIPS and Science Act (the “CHIPS Act”), signed into law by President Biden in August 2022, took significant steps—including authorizing $280 billion in spending—to address underlying national security concerns regarding the longstanding offshoring of critical technological capabilities, a situation that was highlighted during the pandemic which saw significant supply chain disruptions (in part because of China’s “Zero COVID” policy), and which exacerbated the fact that almost all personal protective equipment the United States needed was made in China. In addition to incentivizing investment in U.S. semiconductor manufacturing through more than $50 billion of direct government subsidies, the CHIPS Act also includes guardrails to prevent U.S. companies that receive subsidies under the Act from engaging in significant transactions involving “the material expansion of semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the People’s Republic of China or any other foreign country of concern.” This legislation marked a historic departure for the U.S. Government, which until recently had not significantly restricted private companies’ strategies for offshoring and outsourcing technology outside traditional export control regimes. Following passage of the CHIPS Act, major semiconductor makers quickly broke ground on new facilities located in the United States.

That same month, President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 to boost domestic energy production and manufacturing, as well as to provide direct funding to support the transition to renewable energy sources and to secure domestic energy supply chains. In an effort to relocate electric-vehicle supply chains from China to the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act includes billions of dollars in subsidies for electric vehicles assembled in North America—a move that has rankled close U.S. allies in Europe who roundly have criticized the measure as protectionist and discriminatory against European goods. The European Commission in January 2023 released its Green Deal Industrial Plan, building on the pre-existing RePowerEU initiative and the European Green Deal, to enhance the competitiveness of Europe’s net-zero industry. We expect that the EU response to the Inflation Reduction Act will be further developed during 2023.

In September 2022, President Biden signed an Executive Order directing the investment of another $2 billion into strengthening domestic biotechnology and biomanufacturing supply chains through the National Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Initiative, further exemplifying the current administration’s approach to identifying and directly supporting supply chains across various industries deemed critical for national security.

1. Controls on Advanced Computer Chips

Controlling the manufacture, supply, and export of certain advanced technologies has become a core feature of the U.S. Government’s evolving trade policy toward Beijing. As we discuss in a recent article, the U.S. Government has over the past year employed a variety of methods to strengthen control over strategic supply chains and to limit the export of these key technologies to strategic competitors, including China.

Consistent with its traditional authorities, BIS on August 15, 2022 issued an interim rule to implement new controls on four so-called Section 1758 technologies—named after the section of the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 that tasked the agency with regulating emerging and foundational technologies. As discussed in Section IV.A, below, that measure imposes new restrictions on certain ultra-wide bandgap semiconductors and certain emerging electronic computer aided design software. Both of these restrictions were imposed in a clear effort to limit the ability of U.S. adversaries to produce advanced technologies.

Also in August 2022, BIS used the “is informed“ provision of the Military End Use / User (“MEU”) Rule to, without any formal rulemaking process, privately inform parties that a license is required for exports of specified items due to an “unacceptable risk of use in or diversion to a ‘military end use’ or a ‘military end user.’” A party that receives such a notice is prohibited from exporting the specified items to destination countries identified in the notice without BIS licensing, and such export license applications are subject to a presumption of denial. News reports indicate that BIS leveraged that little-used regulatory provision to, on short notice, restrict at least two U.S.-based semiconductor companies from exporting to China and Russia certain advanced integrated circuits and associated technology commonly used in sophisticated artificial intelligence applications over concerns that the chips could be diverted to a military end use or end user. Although BIS maintains a policy of not publicly commenting on such restrictions on private parties, these sudden and closely targeted controls led observers to speculate that further restrictions were close at hand.

2. Controls on Advanced Computing Integrated Circuits, Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment, and Certain Items Used to Develop Supercomputers

On October 13, 2022, BIS announced groundbreaking and far-reaching controls on advanced computing integrated circuits (“ICs”), computer commodities that contain such ICs, and certain semiconductor manufacturing items destined for China.

As discussed at length in our recent client alert, these new regulations appear calculated to create an effective embargo against providing to China the technology, software, manufacturing equipment, and commodities that are used to make certain advanced computing ICs and supercomputers; to curtail China’s use of these targeted items in the development of weapons of mass destruction, artificial intelligence, supercomputing-enhanced war fighting, and technologies that enable violations of human rights; and to combat China’s “military-civil fusion” development strategy. These complex regulations caused significant upheaval in the affected industries as they were implemented over a two-week period in October 2022 and increased the prospect of other potential efforts to decouple advanced technology supply chains that still link the United States and China.

At the heart of these new export controls is BIS’s addition to the Commerce Control List of new and revised Export Control Classification Numbers. These new ECCNs control certain semiconductor manufacturing equipment and specially designed parts, components, and accessories; specified high-performance ICs; certain computers, electronic assemblies, and components containing such ICs; and associated software and technology. The accompanying new Regional Stability (“RS”) controls apply specifically to these goods when they are destined for the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”)—a destination control that now also includes Hong Kong and, as of January 17, 2023, Macau. Separately, new Antiterrorism (“AT”) controls were also announced at the same time, which further restrict the export of these commodities and associated technology to such highly controlled destinations as Iran, North Korea, and Syria.

BIS also introduced two new foreign direct product (“FDP”) rules and expanded another. Foreign direct product rules expand the scope of U.S. export controls to certain foreign-produced items that are derivative of specified U.S. software and technology. The contours of each FDP rule are unique, but in the case of the new rules targeting China, the FDP rules have been expanded to effectively cut off China’s access to certain foreign-produced advanced ICs, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and items used to develop and maintain supercomputers. The new advanced computing FDP rule brings within the scope of U.S. export controls certain foreign-produced advanced computing items destined for the PRC, as well as certain technology developed by an entity headquartered in the PRC for the production of a mask or an IC wafer or die. Similarly, the new supercomputer FDP rule expands U.S. export controls to certain foreign-produced items used in the design, development, production, operation, installation (including on-site installation), maintenance (checking), repair, overhaul, or refurbishing of a “supercomputer“ (as specifically defined within the regulations) located in or destined for the PRC, in addition to any such items that will be incorporated into or used in the development or production of parts, components, or equipment that will eventually be used in a supercomputer located in or destined for the PRC. Importantly, the current definition of “supercomputer” captures certain data centers that meet the definitional parameters, exemplifying the broad scope of these new controls. Finally, the new controls expand the pre-existing Entity List FDP rule—originally aimed at restricting the flow of certain foreign-produced items to Huawei and its affiliates—to restrict certain foreign-produced items to an additional 28 China-based entities already designated to the Entity List over the past several years for their alleged participation in nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction proliferation, as well as surveillance and other human rights abuses.

New license requirements are also in place for certain items that fall under U.S. export controls for which the exporter has knowledge (defined to cover actual knowledge and an awareness of a high probability, which can be inferred from acts constituting willful blindness) that the item will be used in certain activities (1) associated with the development or maintenance of a “supercomputer” in or destined for China, or associated components or equipment, or (2) destined for end use in semiconductor fabrication facilities in China that fabricate certain ICs (or for which the exporter does not know if the facility manufactures the specified ICs). The ICs specifically targeted by these new restrictions are some of the most advanced ICs presently in existence, including: (1) logic integrated circuits using a non-planar transistor architecture or with a production technology node of 16/14 nanometers or less; (2) NOT AND (“NAND”) memory integrated circuits with 128 layers or more; and (3) dynamic random-access memory (“DRAM”) integrated circuits using a production technology node of 18 nanometer half-pitch or less.

Perhaps the most far-reaching feature of these new export controls are the restrictions BIS has placed on the activities of U.S. persons, even when their activities do not involve controlled U.S.-origin items. Broadly speaking, U.S. persons, including dual nationals and lawful permanent residents of the United States, wherever located, must now apply for licenses to facilitate or engage in shipping, transmitting, or transferring to or within China certain items that are not otherwise captured under U.S. export controls as follows:

- Prohibition Category 1: Any item not “subject to the EAR” that the individual or entity knows will be used in the development or production of ICs at a semiconductor fabrication facility located in China that fabricates certain ICs such as advanced logic, NAND, and DRAM ICs; or in the servicing of any such items;

- Prohibition Category 2: Any item not subject to the EAR and meeting the parameters of any ECCN in Product Groups B, C, D, or E in Category 3 of the Commerce Control List that the individual or entity knows will be used in the development or production of ICs at any semiconductor fabrication facility located in China, but for which the individual or entity does not know whether such semiconductor fabrication facility fabricates certain ICs such as advanced logic, NAND, and DRAM ICs; or in the servicing of any such items; and

- Prohibition Category 3: Any item not subject to the EAR and meeting the parameters of ECCNs 3B090, 3D001 (for 3B090), or 3E001 (for 3B090) regardless of the end use or end user; or in the servicing of any such items. Notably, there is no accompanying knowledge qualifier associated with this prohibition.

BIS subsequently released limited guidance concerning the application of these new rules, including important clarifications such as the definition of “facility” and excluding certain administrative and clerical activities from the new licensing requirement. Additionally, to minimize supply chain disruptions, BIS issued a temporary general license to permit companies headquartered in the United States or in a subset of other countries to continue exporting certain ICs and associated software and technology for specified purposes to their affiliates and subsidiaries located in China through April 7, 2023.

BIS is expected to review the need to impose this range of new export control restrictions on other sector supply chains, including those supporting quantum computing and certain kinds of biotechnology. Although White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan famously summarized the U.S. approach to protecting critical technologies as “small yard, high fence,” as a practical matter, the complex global supply chains involved in producing the most advanced chips and quantum computers will necessitate multilateral coordination to erect any such barrier.

3. Multilateral Controls

In an effort to further restrict China’s access to such critical technologies, the Biden administration has engaged in extensive diplomatic efforts to encourage closely allied countries to adopt similar controls on chip-making equipment. News reports of an agreement among the United States, the Netherlands, and Japan—countries that are homes to some of the world’s most advanced semiconductor equipment manufacturers—suggest that such multilateral controls are imminent. While sweeping, the new export controls on China can only extend so far under U.S. law, and the Biden administration has made clear that multilateral coordination is necessary to counter Chinese technological advances in critical technological fields.

4. China-Related Entity List and Unverified List Designations

While new tools received much of the attention, in 2022 traditional export controls remained a core element of U.S. efforts to counter Beijing as a strategic competitor as the Biden administration again made frequent use of the longstanding Entity List and Unverified List to target China-based entities. As noted in our 2021 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update, the expanding size, scope, and profile of the Entity List has begun to rival OFAC’s SDN List as a tool of first resort when U.S. policymakers seek to wield coercive authority, especially against significant economic actors in major economies. Indeed, in a break from past practice, in 2022 the Biden administration often looked first to BIS to effect its China policy rather than OFAC and its SDN List. Among the more than 60 Chinese entities added to the Entity List during 2022 were numerous organizations associated with advanced ICs and semiconductors such as Yangtze Memory Technologies (“Yangtze Memory”) and Hefei Core Storage Electronic Limited.

Entities can be designated to the Entity List upon a determination by the End-User Review Committee (“ERC”)—which is composed of representatives of the U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, Defense, Energy and, where appropriate, the Treasury—that the entities pose a significant risk of involvement in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. Much like being added to the SDN List, the level of evidence needed to be included on the Entity List is minimal and far less than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard that U.S. courts use when assessing guilt or innocence. Despite this, the impact of being included on the Entity List can be catastrophic. Through Entity List designations, BIS prohibits the export of specified U.S.-origin items to designated entities without BIS licensing. BIS will typically announce either a policy of denial or ad hoc evaluation of license requests. The practical impact of any Entity List designation varies in part on the scope of items BIS defines as subject to the new export licensing requirement, which could include all or only some items that are subject to the EAR. Those exporting to parties on the Entity List are also precluded from making use of any BIS license exceptions. However, because the Entity List prohibition applies only to exports of items that are “subject to the EAR,” even U.S. persons are still free to provide many kinds of services and to otherwise continue dealing with those designated in transactions that occur wholly outside of the United States and without items subject to the EAR.

The ERC has over the past several years steadily expanded the bases upon which companies and other organizations may be designated to the Entity List. In the case of the Chinese entities designated this year, reasons given included engaging in proliferation activities, providing support to Russia’s military and/or defense industrial base, engaging in deceptive practices to supply restricted items to Iran’s military, and attempting to acquire U.S.-origin items in support of prohibited military applications. Notably, in December 2022, 35 Chinese entities (plus one related entity in Japan) were designated to the Entity List for a variety of reasons, including among them, acquiring or attempting to acquire U.S.-origin items to support China’s military modernization.

Throughout the year, BIS also made extensive use of the Unverified List to motivate named entities to comply with end-use checks. A foreign person may be added to the Unverified List when BIS (or U.S. Government officials acting on BIS’s behalf) cannot verify that foreign person’s bona fides (i.e., legitimacy and reliability relating to the end use and end user of items subject to the EAR) in the context of a transaction involving items subject to the EAR. This situation may occur when BIS cannot satisfactorily complete an end-use check, such as a pre-license check or a post-shipment verification, for reasons outside of the U.S. Government’s control. Any exports, reexports, or in-country transfers to parties named on the Unverified List require the use of an Unverified List statement, and Unverified List parties are not eligible for license exceptions under the EAR that would otherwise be available to those parties but-for their designation to the list.

As discussed in greater detail in Section IV.A, below, BIS has implemented a new two-step process whereby companies that do not complete requested end-use checks within 60 days will be added to the Unverified List, and if those companies are added to the Unverified List due to the host country’s interference, after a subsequent 60 days of the end-use check not being completed, the company on the Unverified List will be transferred to the Entity List. In conjunction with the announcement of this new policy on October 13, 2022, 31 Chinese entities were added to the Unverified List, including Yangtze Memory, which, as discussed above, was subsequently moved to the Entity List for presenting a risk of diversion of U.S.-origin items to Entity List parties. Cooperation with end-use checks was also rewarded, with dozens of Chinese entities being removed from the Unverified List throughout the year, including 26 entities on December 16, 2022, after BIS was able to verify their bona fides. Moving forward, we expect the U.S. Government to continue its use of both the Entity List and Unverified List to target additional China-based entities that it finds pose risks to U.S. national security and foreign policy interests.

D. Defense Department List of Chinese Military Companies

The U.S. Department of Defense is required by Section 1260H of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 to publish, and periodically update, a list of “Chinese military companies” operating directly or indirectly in the United States. On October 5, 2022, the Defense Department released its most recent update to the Section 1260H List, which identifies 13 additional PRC-based entities, including facial-recognition software developer CloudWalk Technology, as having links to the Chinese military. Inclusion on the Section 1260H List triggers certain U.S. Government procurement-related restrictions on the listed entities and on contractors that may use certain of their products and services, and can serve as a precursor to designation to other restricted party lists maintained by the U.S. Government such as OFAC’s Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies (“NS-CMIC”) List (which restricts U.S. person investments in certain publicly traded securities) or the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Military End User List (which restricts exports of certain U.S.-origin items). At the very least, companies named by the Defense Department appear to be on the U.S. Government’s radar and may be at elevated risk of becoming subject to such trade restrictions in the future. Many of our clients also use inclusion on the Section 1260H List as a “red flag” for potential diversion to military end uses and end users.

In conjunction with export controls, the Biden administration, acting through the Committee of Foreign Investment in the United States (“CFIUS” or the “Committee”), continued to closely scrutinize acquisitions of, and investments in, U.S. businesses by Chinese investors. CFIUS is reliant on its expanded powers provided under the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018, which we analyzed in an earlier client alert. As discussed more fully in Section V.A, below, CFIUS appears to be especially focused on identifying non-notified transactions involving Chinese acquirors (i.e., transactions that have already been completed and which were not brought to CFIUS’s attention), including through use of the Committee’s increased monitoring and enforcement capabilities.

During calendar year 2021, the most recent period for which data is available, Chinese investors largely eschewed the CFIUS short-form declaration process, filing only one declaration with the Committee. China’s 2021 numbers are also consistent with the period from 2019 to 2021, during which Chinese investors submitted 86 notices, but only 9 declarations. This apparent preference of Chinese investors to forego the short-form declaration in favor of the prima facia lengthier notice process may indicate a calculus that, amid U.S.-China geopolitical tensions, the likelihood of the Committee clearing a transaction involving a Chinese investor through the scaled-down declaration process is quite low.

In addition to the Committee’s purview over inbound investments, there is growing momentum to establish a new outbound investment screening mechanism to restrict U.S. investments abroad. As discussed in Section V.D, below, both the White House and the U.S. Congress have advanced proposals to establish such a regime. Although the scope and contours of an outbound screening mechanism remain uncertain, should one materialize it is highly likely that the Biden administration—whether or not it mentions Beijing by name—would begin by restricting U.S. investments in sectors of China’s economy deemed critical to U.S. national security such as artificial intelligence and semiconductor manufacturing.

Amid continuing advances in Iran’s nuclear program, Washington and Tehran entered 2022 with limited prospects for a return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”), the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement which the Trump administration renounced in 2018. As the year progressed, any hopes for a return to negotiations faded further as Iran shipped arms to Russia in support of the war in Ukraine and cracked down on street protests at home following the September 2022 death of Mahsa Amini at the hands of Iran’s Morality Police. With a return to the JCPOA seemingly not on the table any time soon, OFAC accelerated the pace of new Iran-related sanctions designations during the second half of 2022, and issued an expanded general license designed to facilitate ordinary Iranians’ ability to access the internet.

In an effort to limit one of Tehran’s key sources of revenue, OFAC in June, July, August, September, and November 2022 added dozens of parties to the SDN List for their involvement in the Iranian petroleum and petrochemicals trade. Underscoring the extent of the Biden administration’s concerns about Iranian actors supplying unmanned aerial vehicles (“UAVs”) to Russia for use in conducting attacks in Ukraine, including on civilian infrastructure, OFAC announced waves of UAV-related designations in September and November 2022, and again in January and February 2023. The U.S. Government also warned that “OFAC is prepared to use its broad targeting authorities against non-U.S. persons that provide ammunition or other support to the Russian Federation’s military-industrial complex,” suggesting that additional designations related to shipments of Iranian UAVs to Russia may be on the horizon.

After widespread street protests erupted in September 2022 following Mahsa Amini’s death, the Biden administration announced nine rounds of sanctions targeting Iranian government officials and entities for their involvement in violence against peaceful demonstrators or restricting Iranians’ internet access. Among those designated were Iran’s Morality Police, as well as the country’s prosecutor general and interior minister. More designations of leading members of Iran’s security apparatus are likely in 2023.

As part of its suppression of protests, the Iranian government cut off internet access to the vast majority of its citizens, presumably to limit discussion of the regime’s brutal crackdown and to curtail access to organizing tools. In the wake of these restrictions by the Islamic Republic, the United States in September 2022 announced the issuance of Iran General License (“GL”) D-2, which expands the scope of permitted exports to Iran of certain software, hardware, and services incident to internet-based communications. As we described in an earlier client alert, GL D-2 supersedes and replaces a years-old general license with the aim of expanding internet access for Iranians. As described by the U.S. Department of State, the expanded flow of information enabled by the license is designed to “counter the Iranian government’s efforts to surveil and censor its citizens” and “make sure the Iranian people are not kept isolated.”

Whereas now-superseded GL D-1 only permitted software “necessary to enable” internet communications, GL D-2 permits the exportation of software that is “incident to” or “enables” internet communications. And unlike GL D-1, there is no requirement that the internet-based communications are “personal,” which was a sticking point and compliance burden for the private sector. Among the ways that GL D-2 makes it easier for Iranians to get online, U.S. officials have noted that “most importantly [this] expands the access of cloud-based services,” so that virtual private networks, or VPNs, and anti-surveillance tools can be delivered to Iranians via the cloud. As a practical matter, GL D-2 opens the door for technology companies to export tools and technologies that are listed in or covered by the license, which have the potential to enable ordinary Iranians to more easily access information online and use the internet to communicate with others inside and outside the country.

Consistent with OFAC’s longstanding commitment that sanctions should be reversible in response to changes in circumstances or a target’s behavior, OFAC during 2022 modestly eased sanctions under two of its most restrictive programs targeting Syria and Venezuela.