On Aug. 4, 2020, President Donald Trump signed the Great American Outdoors Act into law. It was, according to the federal government, the “single largest investment in public lands in U.S. history,” with one advocate calling it “a conservationist’s dream.”

The law has two main components: The first part permanently funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which aims to improve access to public lands, especially for recreation. Though the Land and Water Conservation Fund has existed since 1964, it always lacked a source of permanent funding. Now, it receives $900 million per year — not from taxpayers, but mostly from fees paid by oil and gas companies for the rights to drill in federal waters.

The second part of the act bankrolls the National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund to the tune of $9.5 billion over five years. The money will help tackle the backlog of infrastructure maintenance and repairs on public lands, with most of it going to national parks.

Now that the Great American Outdoors Act has been active for a while, has it done what it set out to do? Myke Bybee, legislative director at the Trust for Public Land, seems to think so.

“The Great American Outdoors Act was such an important victory,” Bybee told High Country News. “We continue to celebrate it as a huge win. It has changed our world.”

Bybee, for example, used to spend significant time and resources lobbying for money for the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Now he can focus on getting those dollars spent as efficiently as possible.

What has the Land and Water Conservation Fund accomplished?

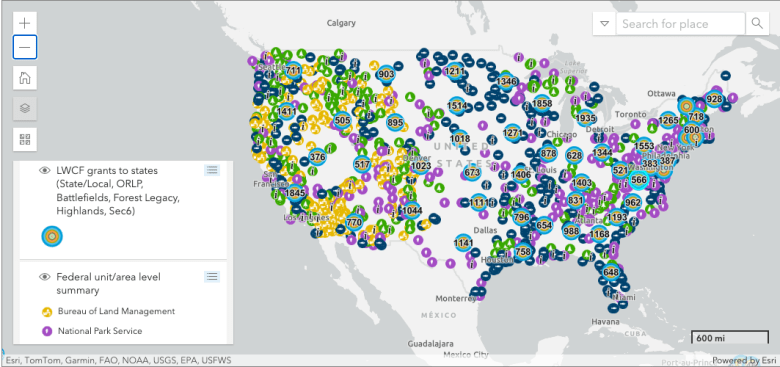

Over the Land and Water Conservation Fund’s 60-year lifespan, it has touched nearly every county in the United States. Bybee said the money often goes toward acquiring private land to improve access to public land: For example, his organization recently used these funds to purchase 50 acres of privately held land in Zion National Park.

About half of the fund’s annual allotment is funneled to state governments, where it can boost equitable access to green spaces. The fund, for instance, helped create Gas Works Park in Seattle and Confluence Park in Denver.

“Oftentimes we think about the Land and Water Conservation Fund as these big federal land projects in the big square states in the West,” Bybee said. “But I want to suggest that where we often see the real impact and benefits to kids’ lives are in these small parks, these playgrounds, these safe, clean spaces.”

To see the Land and Water Conservation Fund’s historical impact on communities across the country, use the interactive map below. (The map has not been updated since June 2022.)

What has the Legacy Restoration Fund accomplished?

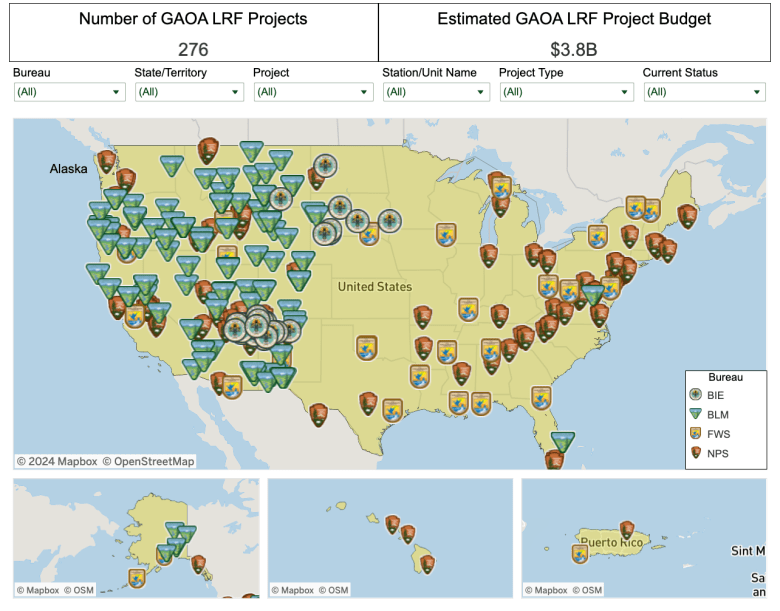

Since 2021, the Legacy Restoration Fund has funded a slew of delayed maintenance projects, both large and small — rehabilitating the Hurricane Ridge day lodge at Olympic National Park ($7 million); replacing a wastewater plant at Grand Canyon National Park ($40.5 million); and rebuilding roads, bridges and water treatment plants at Yellowstone National Park ($317.7 million), among many others.

Legacy Restoration Fund money has also helped repair employee housing and other facilities at schools funded by the Bureau of Indian Education, and improved more than 300 trails, campgrounds and picnic areas. Half of the fund’s projects improve access for people with disabilities.

The Department of the Interior estimates these initiatives have generated roughly 17,000 jobs in local communities and contributed $1.8 billion to the national economy each year.

Here’s a map showing how the money’s been spent so far. (Click on the image to access the interactive elements.)

“Good things are happening,” Bybee said. “This has been a great blip on the radar screen, an important chipping away at that deferred maintenance backlog. But there’s a long way yet to go.”

In the future, Bybee hopes to see more funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund — the $900 million annual allocation has been the same since 1964, when land was much cheaper — as well as permanent funding for the Legacy Restoration Fund.

“Public lands are owned by all of us,” Bybee said. “And it’s important that we all have a chance to use them.”

Susan Shain reports for High Country News through The New York Times’ Headway Initiative, which is funded through grants from the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF), with Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors serving as fiscal sponsor. All editorial decisions are made independently. She was a member of the 2022-’23 New York Times Fellowship class and reports from Montana. @susan_shain