Summary

- A US academic study suggests that airports are managed best privately, by (loosely defined) Infrastructure funds.

- The global study concludes that the type of ownership matters: volume (passengers), efficiency, and airport quality improve substantially under private equity (PE) ownership.

- That definition is not restricted to targeted private equity funds, but it embraces any private sector entity making a large-scale investment into an airport or group.

- The research, covering the period 1996 to 2019, extended to a database of 2,444 airports in 217 countries, of which 437 (5.6%) have been privatised.

- PE airports were found to have had more passengers per flight, and growth in passenger traffic was four times as much, compared with non-PE privatised airports.

- They are more likely to have deregulated airport pricing, which has meant larger aircraft, while the airport’s physical capacity was seen to expand – especially the terminals.

- Non-PE privatisers were found to be more focused on developing countries.

- Competition between airports was shown to “breed better performance”.

- CAPA – Centre for Aviation concurs with most of the findings, but points to potential anomalies concerning the value of non-PE investors and operators and the management quality and service levels they can provide.

- Nevertheless, the study is a very useful tool to help continue to impress the value of privatisation on reluctant politicians in the US.

US study supports the concept of privatisation in the airport sector and advocates for high levels of equity investment from the private sector

While the latest iteration of the report is a year old, with the approach of the Global Airport Development (GAD) Americas conference in Miami at the end of May-2024 it is pertinent to consider the findings of ‘All Clear for Takeoff: Evidence From Airports on the Effects of Infrastructure Privatization’, which was researched by four academics on behalf of the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBEC) as Working Paper 30544.

The report was first published in Oct-2022, and a revised version followed in Mar-2023.

NOTE: hereinafter it is referred to as ‘WP30544’.

Performance secondary factor in decisions on airport privatisation in US

Although the level of performance of an airport has never featured highly in the arguments for and against the privatisation of airports in the United States (as the home of WP30544) – that has tended to be dictated more by the easy availability of alternative methods of financing, and by sometimes deeply ingrained political considerations – the contents of this report are particularly appropriate there now.

The reason is that while the national push for privatising US and Commonwealth airports by way of leasing them that began in 1996, the desire for specific infrastructure-focused investment through public-private partnerships has mushroomed in recent years, and not only in the US. (That push was by way of a since-revised pilot programme and stuttered its way through the starting gate; even now, almost 30 years later, it is still limping around the racecourse like a three-legged nag.)

Moreover, that desire is not limited to airport terminal financing. The PPP (or ‘P3’, as it is known in the US) movement has moved on to embrace supporting infrastructure like cargo terminals, car parking facilities, centralised car rental facilities, people movers, ATC towers and administrative facilities. And it is manifest across the country.

In other words, the privatisation of US airports has not gone away, it has merely changed shape.

Global scope of the study

What is specifically under investigation in the NBEC report is the impact that private infrastructure funds have on the performance of the airports. And that investigation is a global one, not limited to North America.

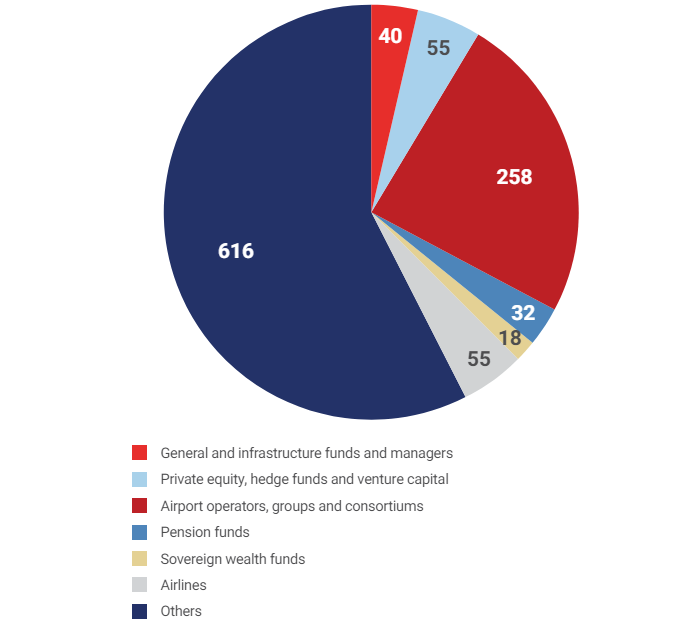

The various types of funds make up a large part of the airport investment community – as shown in the chart below, which was created for a series of reports on sovereign wealth, pension fund and private equity investment into the sector in 2023.

Data is from the CAPA – Centre for Aviation Global Airport Investors Database.

As can be seen, infrastructure funds and asset managers were involved at more than 40 airports globally then, out of 1,100 database profile entries (now 1,021 as of 24-Apr-2024).

And that isn’t to mention the plethora of pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and private equity, venture capital and hedge funds, whose grand total of 145 is more than half the number of airport operators who are investors elsewhere.

(NOTE: in the remainder of this report, CAPA – Centre for Aviation‘s own interpretations of the findings of WP30544 are interspersed with the report’s original observations.)

Fundamentally, WP30544 found that the impact of airport privatisation finds far better airport performance if private infrastructure funds lead the privatisation entity.

The research team began with a database of 2,444 airports in 217 countries, of which 437 (5.6%) have been privatised to some degree or other.

That is not a particularly high ratio. As of 2020, approximately 15%-20% of airports globally had one form or other of private sector financial involvement, depending on which report you read, but the regular annual increase witnessed until that year stalled along with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that ratio has not subsequently increased by much at all.

Indeed, there is evidence of some renationalisation – in Russia and Hungary, for example, and it hasn’t been unheard of before.

As more than 100 of the airports in the report have been owned at least once by a private infrastructure fund (hence referred to as private equity [PE] in their text), the team was able to compare the performance of airports with majority PE ownership and those with none or only a minority stake.

The data extends over the period between 1996, coincidentally the date when the US privatisation pilot programme began, and 2019.

More passengers per flight, higher growth rates, deregulated pricing and larger aircraft in consequence…

Among the results is that PE airports had 21% more passengers per flight. Also, that growth in passenger traffic was four times as much for PE airports compared with non-PE privatised airports, according to the study.

Moreover, PE airports are more likely to have deregulated airport pricing, which has led to airlines using larger aircraft, on average. The airport’s physical capacity was seen to expand, especially the size of its terminals.

(Of course, deregulation does not apply in every case with PE airports. The most ‘PE’ airport in the UK, bearing in mind its ownership make-up, is London Heathrow, which is also the only airport to be directly price regulated.)

… more LCCs too

Although both PE and non-PE privatised airports show increases in the number of airlines and routes – the increases are larger for PE airports, including far larger increase in service by low cost carriers (LCCs). (That will likely be the case if there are larger terminals, which permits part of them, or pier[s]to be designated for LCC use solely).

Airports operated by PE entities are also more likely to score higher in Airport Council International’s annual Airport Service Quality awards. (No mention is made of other similar standards assessors, such as JD Power and Skytrax).

The report’s authors examined why and how the role of PE firms has led to such dramatic changes in performance.

Non-PE privatisers more focused on developing countries

One feature is that non-PE privatisers tend to acquire airports in developing countries, some of which score higher on corruption indexes. In the case of PE privatisers, they are more likely to fear finding themselves to be subject to government standards, such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

In addition, PE tends to target airports with more passengers and routes, while non-PE private targets airports with more airlines and that are more likely to have a competing airport nearby.

In those cases, non-PE ownership has “zero or negative effects” on airline traffic volume, number of routes, passengers per flight, and so on.

Premium gains

Another observation made is that when both PE and non-PE firms bid on an airport privatisation, PE has been seen to win 77% of the time, due to “PE paying a premium because of its greater ability to create value”.

And in cases where the airport is served by a state-owned ‘flag carrier,’ PE ownership generates much larger increases in the number of airlines, and low cost carriers in particular, which suggests that PE ownership leads to reducing or eliminating special privileges for the flag carrier.

That is an intriguing observation in the light of the declining status of flag carriers, some of which are no longer the largest airlines at key public and airports owned by the private sector: such as Paris Orly (public/private) (Air France 11% of capacity); Berlin Brandenburg (public) (Lufthansa 9.5%); London Gatwick (private) (British Airways 13.6% of capacity); and Budapest (private, moving to public/private), where there has been no national flag carrier since 2013.

Each of those airports, apart from Berlin, has a major input from what would be classed as PE owners in the study.

Competition breeds better performance…and that is evident in the example of London

The researchers also found that “performance improvements are substantially larger when there is a competing airport nearby”.

This occurs for both PE and non-PE privatisations, but this effect of competition is “magnified under PE ownership, consistent with PE firms being more responsive to competitive incentives”.

Again, that is a very pertinent observation if one takes (for example) London, UK as an example.

Apart from London being the largest single city conglomeration of airport passengers in the world (with 168 million of them handled in 2023, spread across six airports), it has also the most diverse ownership of any major city. Each of the airports has different owners, and every one of them has at least one part-owner which would be classified as ‘PE’ in the WP30544 study. In the case of Heathrow, Gatwick, Luton, City and Southend airports all the owners (or lessors in Luton‘s case) and Southend all the participants would be ‘PE’.

(But that again raises the question of how accurate the research is when there are a variety of owners. In some cases it can be PE/non-PE/and public).

A stark statement – privatisation consistently leads to better performance only with PE involvement

After describing a number of tests of their data, the authors conclude that “privatisation consistently leads to better performance only with PE involvement. The companies bring with them knowledge of global best practices, new management with higher-powered compensation, and capital”.

All of which have been posited as the raisons d’être for airport privatisation since the concept first began in the 1960s, with Pan Am’s airports division (which subsequently became ‘Avports‘, which is still very much in business privatising small airports in the US, but which would not be regarded as ‘PE’ in this instance).

Service quality is not wholly the preserve of the larger PE-led airport…

These changes lead to new strategies, including investing in capacity expansion, service improvements, and better negotiations with airlines. Because passengers (in many cases) have options – such as one or more alternative airports, driving there, or surface public travel, service quality becomes very important to the PE owner.

(But it could be argued that service quality becomes even more important to the smaller ‘minnow’ airport, which cannot compete by offering the same number of destination or airline options. Or they act as a hub facility, but can ‘roll out the red carpet’ by transporting its passengers rapidly, efficiently and comfortably from arrival point to gate. These airports are far less likely to be owned by PE entities).

…and London City airport is a good example

London City airport, which handled 3.4 million passengers in 2023 and is not permitted to exceed eight million, is a good example of an airport that sits somewhere in-between.

The airport built a reputation among a highly demanding clientele – mainly business travellers from, or to, the financial City of London, which is in two locations – with a ‘six minute from entrance door to gate’ claim, allied to concession-based services.

But it has done so under quite disparate owners: from the construction company (Mowlem) which built it (1988); to an Irish entrepreneur, Dermot Desmond (1995); to a consortium of funds led by Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) (2006); to another consortium, AIMCo, led by a Canadian funds manager together with two Canadian pension funds and the Kuwaiti Sovereign Wealth Fund, which acquired it in 2016.

Most of London City‘s rapid development and its reputation-building actually took place under the first two owners, although it is more constrained by municipal regulation now than it has ever been.

But neither of those two owners could be classed as ‘PE’ to the same degree as the more recent ones.

This study should encourage further investigation into the benefits of long term P3s

This study, WP30544, is certainly a highly significant one, and goes some way towards underpinning the findings of what is a relatively small number of previous studies on the effects of airport privatisation.

It covers a lengthier period, has a larger sample size than predecessors, and is the first to differentiate between PE and non-PE ownership.

Its results will surely encourage further studies of the benefits that could accrue from long term public-private partnership leases of US airports, where the local or state government owners would like their airport to achieve the kinds of performance improvements this study documents.

Who wouldn’t?

Half the bidders in the aborted St Louis lease classed as PE

And it is notable that it is this ‘PE’ sector that formed the majority of bidders for the St Louis Lambert International Airport lease in Nov-2019; a deal that was later nixed by the City’s mayor after coming under pressure from business leaders.

No less than 18 companies or consortiums bid for the lease on that airport, and included among them, mixed up with big operating companies, were organisations such as AMP Capital (now Dexus); Global Infrastructure Partners; Atlantia (now Mundys); IFM Investors; BlackstoneInfrastructurePartners; Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan; Public Sector Pensions Investment Board and OMERS – embracing the US, Australia, Canada and Italy.

In fact, half of the bidding entities could be classed as ‘PE’ by the study’s definition.

As mentioned previously though, those statistics stand in stark contrast to the very weak actual take-up of airport privatisation opportunities on offer in the US since the 1996 pilot programme and the extensions of it in 2018.

As of 2024, they amount to one confirmed deal, in Puerto Rico, while another one, in New York State, was returned to the public sector in 2007, and that was seven years into a 99-year lease. The operator was a British bus company and could not be regarded as ‘PE.’

And, apart from the finalisation of a small privatisation airport deal in Florida, which is pending, that is the measure of it.

Of all the words that have been written in support of airport privatisation in the US – many of them by CAPA – Centre for Aviation – perhaps in the right hands WP30544 will help tip the balance in the boardrooms of municipal and county offices and point them in the direction of who they might wish to work with.

Some report elements unclear – such as the definition of ownership

There are some elements of the study that require some clarification.

For example, some of the data distinguishes between public-private partnership concessions of less than 30 years and ones longer than that, the latter of which are referred to as “sales.” But a sale is sale, a freehold transaction – which is not permitted to the private sector in the US where airports are concerned.

It appears that when the authors refer to “ownership,” in most cases they are actually referring to long term P3s instead.

To PE or not to PE – that is the question

There is also a lack of clarity, at least on a brief initial reading, on multiple segment ownership.

In many countries now – Japan is one example that springs readily to mind – airports can be owned or leased by many disparate entities from both the private sector and even the public one in a majority or minority role, and which belong in both the ‘PE’ and ‘non-PE’ segments.

Take, for example, the airports at Larnaca (the main one) and Paphos in Cyprus, neither of which has any ownership accruing to local or national government but which are each owned instead, by way of Hermes Airports, by nine different entities – including airport operators, a construction company, a mining company, a duty-free specialist, and a couple of brothers who live locally.

The small island of about one million people has services to and from 150 airports in 38 countries in 2024; infrastructure investment is high, and passenger traffic in 2023 was the second highest ever recorded.

And in this case there is little ‘PE’ in sight.

The paper’s central finding, though, is generally supported. That the type of ownership matters: volume, efficiency, and quality improve substantially under private equity (PE) ownership – both following privatisation and in subsequent transactions, and there is little evidence of improvement under non-PE private ownership.

More information:

The paper’s research team was led by Sabrina T. Howell of New York University’s Stern School of Business, and also included Yeejin Jang, Hyeik Kim, and Michael S. Weisbach.

For direct and free access to the full report, see: All Clear for Takeoff: Evidence From Airports on the Effects of Infrastructure Privatization

Further reading – CAPA – Centre for Aviation‘s interview with Kevin Willis, recently retired Director, Office of Airport Compliance and Management Analysis and a key figure in the FAA‘s privatisation of airports in the US: In conversation with… Kevin Willis, a key figure in the FAA’s privatisation of airports in the US