UK government debt prices have taken an unnerving journey south in the past few days. The closely watched ten-year bond has now hit a yield of 4.3%, taking it within a fraction of the level that caused a crisis in autumn 2022.

The cause that time was Liz Truss’s mini-budget, which investors decided jeopardised the public finances, prompting them to dump UK government bonds so aggressively that leading pensions funds were in danger of collapse until the Bank of England intervened.

UK bond yields (ten year)

Trading View

To find out why the is UK back at the brink and how dangerous it could be this time around, we spoke to David McMillan, a Professor of Finance at the University of Stirling.

Why are bond yields close to crisis levels again?

The simple answer is inflation. The annual headline rate came down to 8.7% in April compared to double figures in March – that was expected because April was the first month in 2022 to see a big inflation jump after the Ukraine invasion, so the year-on-year comparison is less severe now. But it was expected to be down to 8.2%, so it has been a disappointment.

This is mainly because of core inflation, which strips out things like food and energy that fluctuate a lot. Central banks like the Bank of England use core inflation as a more stable projection of where prices are going, and it rose to 6.8% compared to 6.2% in March. The bank was probably not expecting that to happen. Service sector inflation is also sticking around the 7% mark.

A week ago the consensus was that the Bank of England maybe wouldn’t have done any more interest rate rises after 12 in the past 18 months, especially with the US Federal Reserve apparently now pausing, but now the expectation is a few more 0.25 point rises: maybe a total of 0.75 points or even 1 percentage point over the next year. Bond yields are rising to reflect that.

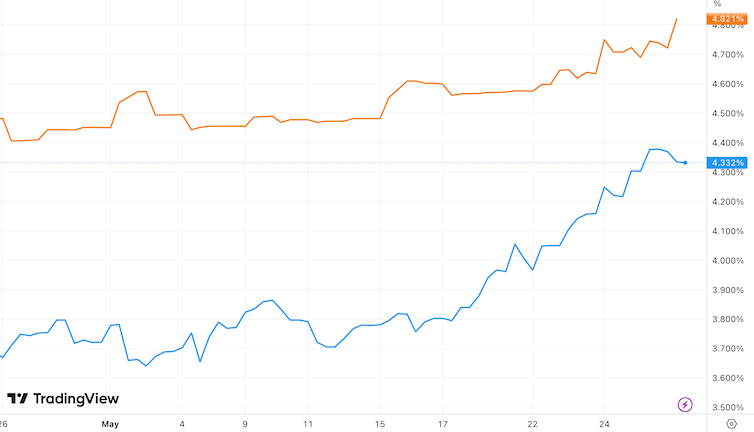

Also notice that it’s not just ten-year bonds: the yield on three-month bonds is 4.8%, meaning that you can get paid more for locking up your money for three months than ten years. Normally it’s the other way around. When the market inverts like that, it’s a sign that it is pricing in a recession. The IMF has just improved its forecast for the UK, saying it doesn’t expect a recession in 2023, but it’s on a knife edge to say the least.

UK gilt yields (ten year v three month)

Trading View

Are Jeremy Hunt’s latest comments unhelpful?

The chancellor is saying that a recession is a price worth paying for curbing inflation for political reasons. The government has set itself the target of halving inflation this year.

photocosmos1

It will get the credit if this happens. On the other hand, if inflation stays higher, Hunt is signalling to people that the Bank of England will be to blame, potentially creating a win-win for the government. But I don’t think the market is likely to be much influenced by what Hunt is saying.

Is the US debt ceiling row making a difference?

The debt ceiling is used for political horse-trading in the US. As always, there’s a general expectation a deal will be done. What does affect the UK is what happens with the pound. If there is a danger that the US will increase interest rates, that will make the US dollar relatively more attractive and could drive down the value of the pound.

Since the UK is a major importer, a weaker pound could make inflation worse, so if the Fed did continue to raise US interest rates, there is a view that the Bank of England might do likewise to defend the pound.

Will yields surpass the levels last autumn?

I’m afraid they probably will rise, roughly in line with the Bank of England base rate. The only unknown is how aggressive the bank will be.

Does that mean another panic for pension funds?

Not necessarily. The problem for pension funds in 2022 was the speed at which yields moved after the mini-budget, around 1.2 points in about four days. Pension funds were using UK bonds as collateral on major market bets. When the value of that collateral fell so sharply, they faced margin calls from their lenders that meant they were in danger of losing their whole bets because they didn’t have the cash to make up the value of the collateral, which could have made them insolvent.

New Africa

This time the move has been more like 0.5 points over the same period, so it’s not quite as dangerous. Meanwhile, the market has generally been positive for pension funds lately. The UK stock market has done well, climbing over 10% since the autumn debacle. Also, pension funds have been benefiting from higher interest rates because it means they’re putting more of their money into higher-yielding bonds as previous investments reach maturity.

Finally, funds have reduced their exposure to liability-driven investment strategies (LDIs), which were the parts of their investment portfolios that blew up in 2022.

Are there increased risks of contagion from the US banking crisis?

Higher interest rates have in one sense been good news for banks because they’ve been able to make a greater return on their investments while getting away with not paying higher saving rates to customers. In the US, this has prompted lots of customers to withdraw their deposits and put them into other things like money market funds, which has seen some banks running out of cash, but we haven’t seen that so much in the UK.

Also, US mid-sized banks have had weakened balance sheets because the regulations were relaxed under President Trump, which has made them more vulnerable to bank runs. By comparison, the UK has more stringent regulation.

It’s certainly the case that UK banks’ balance sheets will be weakened by their bond holdings losing value. Whether it leads to contagion possibly depends on how aggressively the Bank of England responds to inflation. If it just does another two or three 0.25 point rises, the UK banks may come through without serious problems.