“Violent crime, drug abuse, teen pregnancy, illiteracy, joblessness—these are some of the hallmarks of what has come to be called ‘the underclass,’” Isabel Sawhill wrote in a 1989 Public Interest essay. “Everyone has a theory, but no one really knows why the social fabric of certain communities has deteriorated so badly.”

Sawhill’s words came at a turning point in the history of social policy. Between the 1960s and the 1990s, all of the enumerated rates hit disturbing highs, driven by communities of concentrated disadvantage—home of the “underclass.” The richest nation in the history of the world discovered that alongside wealth came new pathologies, ones which once-ascendant liberal meliorism seemed unable to address, and indeed was likely exacerbating. The conservative policy renaissance of the 1980s and ’90s, in turn, was largely about providing alternative approaches, particularly by reforming the government programs which, conservatives argued, were producing the underclass phenomenon in the first place.

This past is prelude to a different suite of pathologies that affect what might be called today’s underclass. Six years ago, demographer Nicholas Eberstadt threw light on the “invisible crisis” of the men who make it up. In Men Without Work, Eberstadt documented how millions of American men had quietly vanished from the workforce, instead living lives of idleness and dependency on family and the dole. Now, Eberstadt has released an update to the book, addressing the surge of labor-force dropout following the COVID-19 pandemic. It is a timely warning to both sides of the aisle as to the challenges social policy still faces.

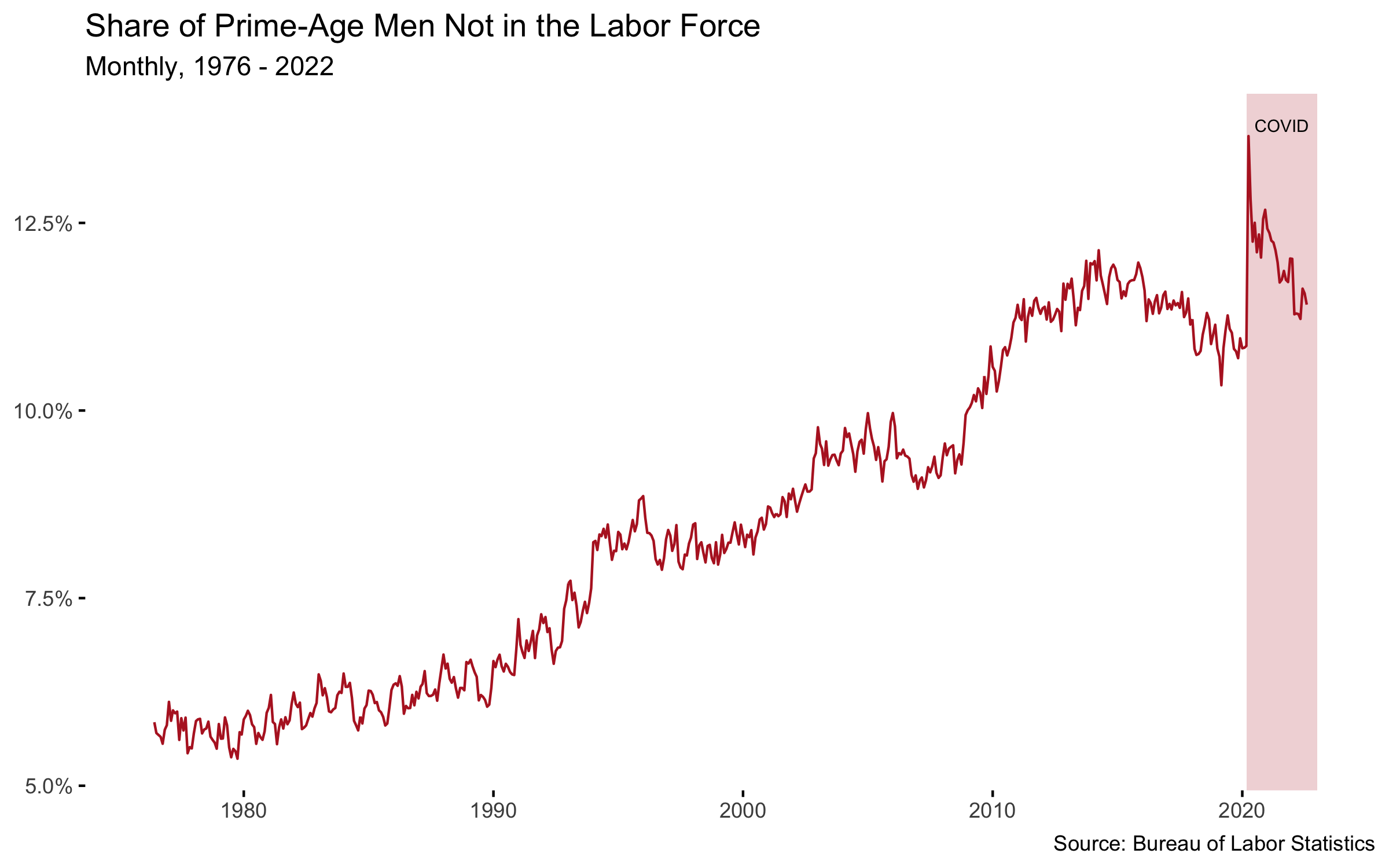

Men Without Work is, essentially, a book about a mouthful of a statistic: the prime-age male labor force participation rate. In layman’s terms, that’s the share of working-age (i.e., 25 to 54) men who are either employed or looking for work. As Eberstadt explains, this rate has been steadily declining since the 1960s. That means millions of men who would have worked decades ago are now not only not working, but not even actively looking for work.

Drawing on government and nonprofit data, Eberstadt paints a picture of these men. They dedicate far more of their day to recreation and entertainment than employed men and women, and barely any time to childcare, particularly relative to non-employed women. They derive their income principally from other people in their households and the web of transfer programs—Social Security Disability Insurance, Supplemental Security Income, etc.—on which they are increasingly dependent. They are at high risk of drug use and, although Eberstadt argues that it is hard to estimate the exact incidence, seem more likely to have a criminal record.

In the updated introduction, Eberstadt revisits these themes for the post-pandemic world. He argues that the trend of male labor force drop-out has continued unabated, noting new research on the relationship between incarceration and subsequent unemployment. And he contends that pandemic policy, particularly the dramatic expansion of unemployment insurance, exacerbated the drop-out problem and explains why this labor force participation rate among men remains elevated above pre-pandemic levels.

The latter claim is, of course, the subject of live debate. But the most important takeaway from Eberstadt’s revisit seems incontestable: Even in the light of a global pandemic, male labor force drop-out continued on its steady upward rise.

Which returns us to the “underclass.” In the late ’80s and early ’90s, much of the focus of social policy was on poor, unwed mothers—then pejoratively labeled “welfare queens”—and the children they bore, particularly the sons thought to be driving the crime wave. Many changes to policy, particularly the 1996 Clinton welfare reform, were targeted at shifting incentives for these households, with the goal of reducing “violent crime, drug abuse, teen pregnancy, illiteracy, joblessness,” and all the rest.

Eberstadt’s argument, in essence, is that the group attended to by the last generation of social policy were really just the tip of the iceberg, made visible by the gruesomeness of their conditions. Beneath the surface, a mass of non-working, welfare-dependent men made pathology into a lifestyle. And while welfare reform probably put a dent in at least some of the then-concerning pathologies, it appears to have had no discernible effect on male labor force drop-out, likely because it left much of the disability system untouched.

Eberstadt has not updated his original, sparse recommendations: promote business development and growth, reform disability insurance, and do more to both count the formerly incarcerated and reincorporate them into the workforce. But in addition to these, one might infer a note for each side of the political divide. For the left: the utopianism which the COVID government spending elicited is misplaced. We have a model for what a more welfare-dependent society looks like, and it is not a pretty one.

For conservatives, Eberstadt’s book is more of a challenge. A generation ago, the right engineered a profound change in the operation of the American welfare state, one which—in Eberstadt’s estimation, at least—worked its intended effect of reducing concentrated pathology. But that change barely touched the “invisible crisis.” If the liberal answer is to spend, spend, spend, then conservatives need a different one—one which is, alarmingly, not of yet forthcoming.

Men Without Work: Post-Pandemic Edition

by Nicholas Eberstadt

Templeton Press, 252 pp., $12.95

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor at City Journal.