Key points

- The first wave of climate risk reporting by UK pensions is not leading to a shift towards green investment strategies

- Availability of more and improved data for future disclosures could drive more strategic change

- Pension funds are using climate risk reporting to corroborate evidence for existing decisions

- More detailed regulations could drive further climate-friendly impact investment

Climate risk assessments are making no difference to pension funds’ action to reduce climate change impacts, according to a new survey of UK pension schemes. Initiated by non-profit Pensions for Purpose, the study was prompted by the first wave of obligatory reporting – introduced in October 2021 – based on the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations. They affect larger occupational pension schemes and authorised master trusts.

“The Department of Work and Pension’s decision to make TCFD reporting compulsory was probably to force change in climate action but there was no strong evidence of that from the funds that we interviewed,” says Karen Shackleton, chair and founder of the charity, which promotes impact investment. She suggests that this finding might change following several waves of reporting and once trend data has come through.

Scenario analysis

Certainly, many pension schemes publishing their TCFD reports have uncovered a variety of useful nuggets of information. Among the new activities the TCFD required is scenario analysis, in which current investments are compared to several differing future scenarios relating to the extent and effectiveness of climate change action.

Having carried out this exercise, Smart Pension, a master trust with assets of £2.5bn (€2.8bn), found that younger pension scheme members could experience slightly more risk than people in other age groups. After comparing the effect of three different scenarios – ‘Green revolution’, ‘Challenging times’, and ‘Head in the sand’ – to the baseline pension sum, it noted a reduction of 2-4% in pot size for the younger cohort.

It also said members with a medium-term horizon face slightly more risk than the baseline, but have unchanged average expected outcomes, while members closer to retirement are relatively immune from expected climate risks.

The TCFD analysis has helped the investment managers understand their portfolio better in terms of climate impacts too, shining a light on potential areas of adjustment. “Commodities and energy companies did pretty well financially and had a slightly bigger weighting in portfolios than we imagined, which meant itself that emissions were slightly higher than we thought,” says Fiona Smith, investment proposition manager at Smart Pension. The selection of metrics not used before, such as emissions intensity, was another benefit from the experience. Emissions intensity helps refine comparisons between investments.

Michael Marshall, head of sustainable ownership at Railpen, the asset manager of the £37bn railways pension schemes, says scenario building was neither easy nor necessarily useful.

“There’s a difficulty with assigning a probability to some given scenario outcomes. It’s all well and good to say how assets and liabilities perform in a 1.5°C versus 4.0°C temperature-increase scenario but if you can’t assign a probability what are you going to do about it?”

Nonetheless, Railpen concluded from the analysis that a lower temperature increase is better from an economic perspective than a higher temperature scenario. It also found that the greater number of deaths in a 4.0°C-increase scenario may be likely to affect liabilities and funding levels.

Debt data gaps

Data gaps are numerous, affecting the quality and reliability of the assessments of both risk and impacts. Respondents to the Pensions for Purpose survey found many inconsistencies in emissions calculations between asset classes. Comparing data from different asset managers was not always straightforward, making it difficult to calculate the whole portfolio’s emissions consistently.

Scope 3 (value chain) emissions data were among the hardest to obtain. “The [scope 3] data is so much weaker, that trying to make decisions based on it would be foolish,” said one manager from the Local Government Pension Scheme. The investment officers at both Railpen and Smart Pensions suggested research from several other sources would also improve their understanding.

Environment, social and governance (ESG) data relating to private debt, sovereign bonds, corporate climate transition plans and real estate are all among the most significant data deficiencies noted by the pension funds.

Satisfying the regulator

Commenting on the survey, Shackleton of Pensions for Purpose is wary that it could become a tick-box exercise, performed simply to keep the regulator happy. The TCFD output, she says, is not being used by the majority of pension funds to help them inform climate change strategy and move forward by engaging and advocating more for greener investment. Instead, it focuses on portfolio decarbonisation, rather than active solutions.

“The TCFD requires pension funds to report on emissions of investments but not necessarily to communicate investments in solutions,” Shackleton says. Although TCFD does require reporting on opportunities, this is distinct from solutions. These could include divestments and communication around that, as well as active engagement and portfolio diversification into more impact investment.

“It’s easy to come across as green in TCFD reporting but in terms of climate action or impact, what are you actually doing to green the real world, as opposed to your portfolio? It’s very important to differentiate them.”

Marshall of Railpen suggests this is a misinterpretation of the regulatory requirements. “Is the progress from TCFD reporting expected towards some temperature goal or policy objective, or is it towards being even better managers of financial risk for beneficiaries? Your answer to whether TCFD reporting is effective is different, depending on what you assume the objective is,” he says.

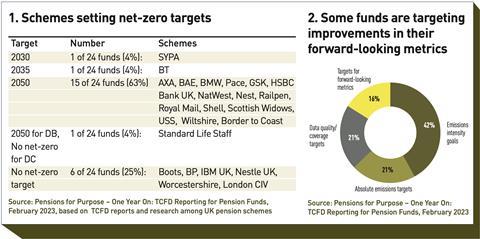

The regulations do not mandate net-zero targets that are in line with the UK government’s net-zero policy. That is because the government is concerned that trustees could breach fiduciary duties, particularly if the net-zero target is contrary to the beneficiaries’ best interests.

Policy makers also fear the risk of mass divestment from higher-carbon firms transitioning to net zero. This, they state in regulatory briefings, could mean pension savers continue to experience the impacts of polluting firms while their trustees were unable to hold the firms to account.

Nevertheless, Marshall indicates that working in the beneficiaries’ best interests does require a greener strategy. “Even if you are only motivated by the financial sector need to pay pensions, it’s still in your interests to work to a 2.0°C scenario.”

Stimulating climate-friendly investment

Many pension schemes are already committed to this pathway. Besides TCFD disclosures, forums such as the Net-Zero Asset Owners Alliance, as well as pension members themselves, are all driving climate-focused investment approaches.

While the effectiveness of TCFD disclosures could grow once data improves, the stimulus from TCFD so far has been limited. “A lot of the funds we spoke to said that their trustees had already made decisions around climate change independently of TCFD reporting but it was useful to corroborate decisions they were taking,” says Shackleton.

Greater regulatory granularity could more effectively stimulate an investment strategy switch towards more climate-friendly, and impact investment in particular, she adds. For example, governments could require greater examination of potential greener or socially beneficial investments. This is because headline risk-adjusted returns on such investments might not at first sight look particularly attractive.

“It’s about doing proper due diligence on investment opportunities and understanding how they can contribute to total portfolio profile, but the government focuses on the financials, fiduciary responsibility and risk-adjusted returns,” she says. This may prevent a more nuanced understanding of the investment.

However, there are grey areas in the regulations, which allow some diverging interpretations on how to act according to fiduciary duty by individual pension schemes. Shackleton suggests it should be clearer what a scheme can and cannot do. “It’s entirely possible that some pension funds are using fiduciary duty as a barrier [to climate action] because they don’t want to have to think about it.”

Frameworks for analysing climate risk

The UK Pensions Regulator recommends pension schemes conduct climate-risk scenario analysis using a range of representative scenarios as set out by the Network for Greening the Financial System, based on three initial scenarios:

● An orderly 1.5°C scenario. This will meet the requirement under the climate change regulations to undertake one scenario with a global average temperature increase within the range of 1.5°C to 2.0°C above pre-industrial levels. [Users] decide to use 1.5°C as this aligns with their net-zero ambition.

● A disorderly 2.0°C scenario. [Users] believe broader action on climate change may need to happen – for example, around 2028 to 2030, if the actual level of global decarbonisation achieved is significantly less than that required by 2030 under the Paris Agreement.

● An orderly 2.5°C scenario. This is closer to the best estimates of 2.6°C to 2.7°C warming by 2100 that some market commentators believe will be the outcome from COP26. [Users] believe that this scenario will also give them some insight into the potential physical impacts and risks that longer-term, high temperature scenarios might have.

Peer and regulator pressure

Pension funds do recognise that TCFD reporting is likely to play a significant role over time in creating regulatory and peer group pressure. At the same time, stakeholder comparisons can shift investments and influence wider society. In its TCFD report, Smart Pensions draws attention to the wider influence of society, and the limitations of its powers despite climate-friendly investment strategies. It states that strategic asset allocation alone will not consistently improve the management of climate risks for all members.

This is because of the actions by major players such as governments and large companies which are not easy to predict. “Part of this is out of our hands…. but we are doing everything we can,” says Smith.