An Oxford-based start-up has raised $30mn in funding to develop RNA medicines for liver disease, testing its drugs on hundreds of donated human livers kept alive in its labs.

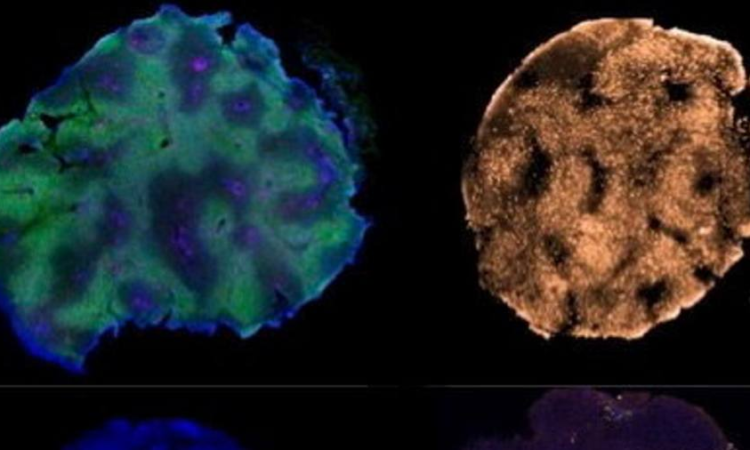

Ochre Bio has already analysed data from more than 1,000 diseased livers in collaboration with Oxford university in an approach called deep phenotyping, which combines imaging, genetic and biochemical analysis to discover the underlying causes of disease.

The new funds will help pay for the next stage: translating biological insights from the initial research into RNA-based medicines. Drug candidates will be tested in hundreds of human livers kept alive at what the company calls its “Liver ICU” in New York.

“We realised that a challenge in tackling liver disease, as in a lot of chronic diseases, is the lack of good models,” said Jack O’Meara, Ochre chief executive. “We can solve liver disease in mice but we haven’t been able to do it in humans yet. Animal models don’t recapitulate the disease well.”

Instead, Ochre is using human organs for pre-clinical research. “Our Liver ICU takes donor livers that can’t be used for transplant because they are slightly diseased or old or fatty,” said O’Meara. “We keep them alive on OrganOx perfusion machines for five days plus, while we study the effects of our RNA therapies on the liver physiology.”

Investors in the Series A financing round, which followed $10mn seed funding in June 2021, include Khosla Ventures, Hermes-Epitek, Backed VC, LifeForce Capital, Selvedge, AixThera, LifeLink, and individuals from the biotech industry.

Ochre is one of many biotech companies coming to see RNA technology as a fast and reliable route to new drugs. It focuses on a category called siRNA (short interfering RNA) molecules with about 20 biochemical units representing letters of the genetic code. These block the transmission of a specific gene whose products are harmful to health.

“The technology speeds up our development timeline,” said O’Meara. “We can go from seeing a target in our genomic data to synthesising an siRNA drug candidate to testing it on a human liver in a matter of days rather than months or years.”

The company is aiming first to produce a compound that extends the life of transplanted livers, with pre-clinical testing in New York next year followed by clinical development in patients in 2024.

“We are focused on liver metabolism, to make donated organs more reliant to cell stress,” said O’Meara.

In the longer term Ochre intends to produce treatments for chronic liver diseases, often associated with excess fat building up in the organ, which are the third-largest cause of early death in the UK and other industrialised countries.

Peter Friend, professor of transplantation at Oxford university, who has worked with Ochre researchers but plays no role in the company, said he had “great enthusiasm” for the “very exciting” work the company was doing.

“The concept of first using an isolated organ to identify the genes associated with disease and then silencing those genes through siRNA before going into clinical trials seems to me extremely elegant.”